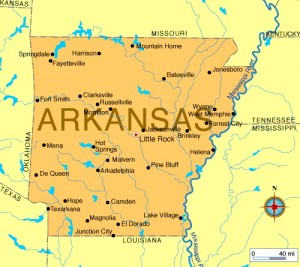

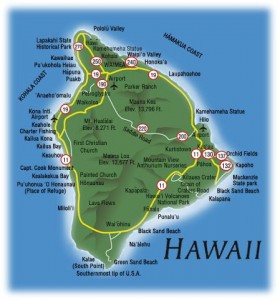

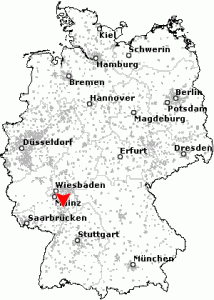

We live north of San Francisco in Marin County, where we have a house that is too small and too expensive on a hectare (two and a half acres) of beautiful California terrain. Henceforth this area shall be known as the Piliwale Andrew hectare.

I sit here writing this web log and look out the window at a railing where birds come to find the birdseed that Elise so kindly provides for them. I’m so glad that we decided to replace our windows, as if we hadn’t, we wouldn’t have the opportunity to see these beautiful birds that have decided to pay us a visit. My friend had told me about a company called, Graceland Windows (https://gracelandwindows.com/) that they used for their replacement windows and they had some great designs on there which would enable us to get a better view of the birds. Unfortunately, though we don’t live in the area so we had to use a company that was more local to our area. If we ever moved to Texas, we will definitely consider using this company. For the time being though, I’m going to enjoy looking at the birds through our windows. Also, I often see them in our outdoor home security cameras, pecking awaty at the lawn or drive. They’re relaxing to watch.

We get some good views of these fascinating and varied creatures.

There is a family of foxes who live on the Piliwale Andrew hectare, a lot of hungry deer, bobcats, skunks, a snake or two, racoons, coyotes, occasionally a mountain lion, but what we see and hear mostly are birds.

At night we often hear, but rarely see, the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus). I love their lonesome sound.

This little valley where we are has been home to Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura) probably for thousands of years. They stretch out their wings to dry and then circle lazily overhead, riding the thermals and living the good life.

The Turkey Vulture will not eat anything that is alive, and they are one of the few birds with a sense of smell.

The vultures are very comfortable here and perhaps twenty of them circle around and come to rest on various tree stumps near our house. This is their laughing place.

The Corvid family (crows, ravens, jays, magpies) is well represented. There must be forty crows who carry on and carouse in the pines, cawing and gossiping, squabbling and commenting loudly on anything that catches their attention. Crows can be taught to “talk” in captivity. They actually practice their vocalizations. You can hear them. They do this even in their sleep. Their ability to mimic is uncanny. They can mimic a squeaky door closing if they choose.

These birds are larger than you might think. Seeing the occasional one who lands on our railing reduces all of us (two humans, a dog and two cats) to a kind of reverential awe. Our crows are nearly the size of eagles.

Common Ravens (Corvus corax) are serious carnivores and their search for food leads them to live in more varied habitats than any other California bird. They eat road kill, any kind of meat they can find in dumps, crickets, grasshoppers and almost anything else.

The Steller’s Jay (Cyanocitta stelleri) is also an improbably large bird with a crest, comb, topknot, whatever you want to call it. They are raucous, noisy and thieving. They will eat other birds and they often imitate Red-tailed Hawks to frighten intruders.

You can see clearly with the jays that they are descended from dinosaurs. They have an otherworldly look and their behavior is aggressive and predatory. Ornithiscian dinosaurs, they will eat almost anything and rob eggs when they can.

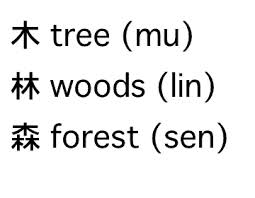

Woody Woodpecker in the Warner Brothers films has a characteristic call that is based on bop rhythms, popular music in the 1940s when he was created, but the pileated woodpeckers around here have a call that is quite similar to Woody’s. You recognize it right away. “And, then I said Baby!” If you sing that very quickly on an ascending scale, you will hear the woodpecker cry.

Our woodpeckers bore hundreds of holes in the trees. They have an extra backward pointing toe for clutching the bark and they lean on their strong tails while working. Woodpeckers have a stiff extending tongue for insects and their eggs.

When you first hear them you think it is someone hammering a nail somewhere.

They knock busily against the tree trunks looking for insects and making nests. I hear them right now hard at work.

Pileated Woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus) like dead or dying trees and we have a lot of those.

The Downy Woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) often selects nest holes on the downward side of leaning trees, where gravity can hinder any tree climbing predators.

The Downy is a small woodpecker, the smallest in North America, and it likes to live around bay trees. It drums loudly on dead limbs.

In the spring we see Olive-Sided Flycatchers (Contopus borealis) who like our wooded canyon in the coastal lowland and so come here to breed.

Olive-Sided Flycatchers spend the winter in Central America. Lucky them. That’s a lot of flying, though.

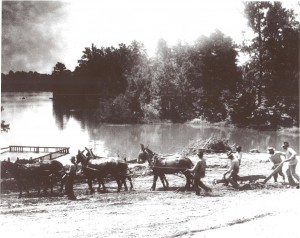

Western Wood-Pewees (Contopus sordidulus) come see us in about mid-April to early June. They and the Flycatchers have a crest or comb which makes them look distinguished. We have an “ephemeral” stream running through the Piliwale Andrew hectare and the Pewees like that. That “stream” becomes a raging torrent in February. My friend Clark brought his metal detector here one day and found a 1900 dime in the water.

The towhees might be the bird we see most. This is the California Towhee. which resembles a large, good looking sparrow. The plumage is very even and smooth.

The towhee is a handsome bird with a patch under the tail, called the crissum. One of the subspecies of the towhee is called crissalis because of this patch.

Rufous-sided Towhees (Pipilo erythrothalmus) have regional accents. The ones in California talk like surfers. No, no, just kidding, but they do sound quite different from eastern towhees. Their call can sound like a buzz.

Towhees like to eat nuts, seeds and fruits.

Spotted Towhees (Pipilo maculatus) like to live near the ground but I see them on our railing pecking at nuts and seeds. They are also sparrowlike.

Males are gleaming black above (females are grayish), spotted and striped with brilliant white. This is a sparrow in overdrive.

Sometimes we see a Chestnut-backed Chickadee (Poecile rufescens) and think it is a towhee.

This is a handsome chickadee that matches the rich brown bark of the coastal trees that it inhabits.

The Chestnut-backed Chickadee is the species to look for up and down the West Coast and in the Pacific Northwest but especially on the Piliwale Andrew hectare. I saw one today in a tree out by the “river,” actually a trickle through the rocks at this point, though, I repeat, a raging torrent in February. Riparian pride is strong on the hectare.

Active, sociable, and noisy as any my little chickadee, these Chestnut-backed Chickadees move through tall conifers with titmice, nuthatches, and sometimes other chickadee species.

I have seen these birds in the shrubs in the heart of San Francisco. They seem at home everywhere.

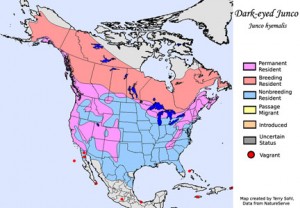

Dark-eyed juncos are sparrows that nest on or near the ground in forests. In winter, they typically form flocks and often associate with other species. It’s fun to watch their beaks move as they “chew” their food. When they land, Juncos will fold their white feathers under, perhaps to escape detection by falcons and hawks.

When disturbed the entire Dark-eyed Junco flock suddenly flies up to a tree, usually perching in the open and calling in aggravation at the intrusion. I like to see animals talking back this way.

The House Wren (Troglodytes aedon) is a plain brown bird, very widely distributed. You probably see them everyday. They nest almost anywhere and will sing incessantly.

Bewick’s Wrens (Thryomanes bewickii) have a very long tail, tipped in white which they flick and jerk side to side. These hyperactive vocalists belt out a string of short whistles, warbles, burrs, and trills to attract mates and defend their territory, or scold visitors with raspy calls.

The Red-winged Blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus) have scarlet-and-yellow shoulder patches they can puff up or hide depending on how confident they feel. Females are a subdued, streaky brown, almost like a large, dark sparrow. We always like to see them because they mean spring is coming, plus, they are a beautiful bird.

The hawks sit up high where they can see everything with their extremely acute vision. This is a Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii). They like canyons like ours with rivers or creeks running through them.

Accipiter striatus (Sharp-Shinned Hawks) like broken woodlands of coniferous, deciduous or mixed forest, so the Piliwale Andrew hectare is perfect for them. They are more common than the Cooper’s Hawk.

The Red-Shouldered Hawk (Buteo lineatus) has its main San Francisco Bay population center in Sonoma and Marin Counties, so we see a lot of them.

The Red-Tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) is hunted as the “chicken hawk,” but this bird is far more valuable for rodent control than for its occasional taking of a chicken. We value this hawk and wish there were more of them on our hectare.

The Red-Tailed Hawk breeding season begins with a spectacular sequence of aerial acrobatics. Male and female fly in large circles and gain great height before the male plunges into a deep dive and subsequent steep climb back to circling height. Later, the birds grab hold of one another with their talons and fall spiraling towards earth. This has to be the origin of several ancient myths (Icarus comes to mind). Here is probably the origin of another myth: Red-Tailed Hawks are monogamous and they mate for life.

The American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) is the smallest falcon in North America and is the smallest American raptor. It will often hover over its prey, deciding before diving. We see them maybe more than any other falcon or hawk. This kestrel, the only kestrel in the Americas, has three basic vocalizations: the “klee” or “killy”, the “whine”, and the “chitter.” The “klee” is usually delivered as a rapid series – klee, klee, klee, klee when the kestrel is upset or excited. This call is used in a wide variety of situations and is heard from both sexes, but the larger females typically have lower-pitched voices than the males.

The Wild Turkey (Meleagris galloparvo) was very rare here in Marin after the great hunting slaughter of the 1870s, but since the 1960s, these turkeys have been reintroduced several times and are now a very successful species. You see them in any open field, often contending with the cattle on Flander’s Farm down the road on Sir Francis Drake Boulevard. The males strut around and show themselves to the females. It’s all very educational.

Wild Turkeys look like the classic Thanksgiving Turkey, especially the males with their preening, overweening behaviors. The females mostly wander around ignoring such ostentation, but it is difficult to enter the mind of a turkey. She may have her own designs, unknown to us. They probably center around reproduction and the continuance of the species.

I always think of the turkey and the chicken as Indian birds, because, if you really look at them, it seems as if they recently arrived from the Subcontinent. They are too ornate, too exotic, too beautiful and too obviously related to the peacock to originate anywhere around here.

We on the Piliwale Andrew hectare are vegetarians, so we observe these feathered bipeds with great interest but not great hunger. We hear chickens in the morning, as we hear the Great Horned Owl at that time, but we are up long before they are, working, toiling, scratching for worms ourselves, indifferent to their carnal attractions, but always aware of their beauty.

How do California Quail survive? They are slow, they are stupid, their call is distinctive and they are very easy to see. Every predatory animal within reach must be intent on their immediate slaughter, and yet they live from year to year scampering along with little regard for safety. Our cats regard their comings and goings with great interest and yet the quail still live… how? They have large broods for one thing. They can run, walk, really, very fast, fast enough to get out of the way of an onrushing car. They will only fly as a last resort. They are like island birds that way.

Mountain Quail (Oreortyx pictus) walk upslope in the summer and downslope in the winter. Quail travel in flocks except when paired for breeding. They have a curious, guttural cry which some people interpret as “chi-ca-go,” which is as good a way to describe their vocal as any. That song is very low and in the back of the throat. Quail, pheasants, turkeys and chickens all eat grain and they are all related.

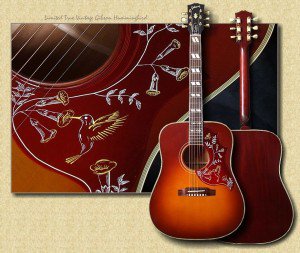

I usually hear hummingbirds before I see them. When I am gardening I hear a buzz and think it is a large fly, but turn to see the hummer. This is the Black-Chinned Hummingbird (Archilochus alexandri).

We leave our doors open a lot and we have a skylight, so hummingbirds will fly in and then try to escape upward to the skylight. Which reminds me, we are currently in the midst of a few home renovation projects and are actually thinking of replacing our skylight soon. We have been looking at DaLyte residential skylights for some inspiration. If hummingbirds buzz against the glass long enough, they die of exhaustion, so there is always a great rushing around for ladders and brooms to try to show them the way out. The trick is to catch them when they are really tired and then they will land on the broom and we can convey them outside. Easier said than done. Anna’s Hummingbird (Calypte anna) is a frequent visitor who is often seen flying backwards.

Allen’s Hummingbirds ( Sealasphorus sasin) visit us early, somewhere from January to March.

This is a Canada goose washing. When we leave the Piliwale Andrew hectare and drive anywhere we see these beautiful birds in ditches, streams and ponds. They breed here and in Canada. They nest on the ground, but sometimes build nests in trees too.

The goslings follow their parents and learn what to eat.

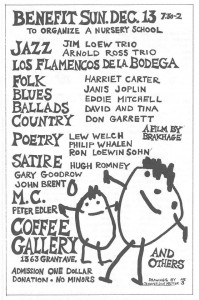

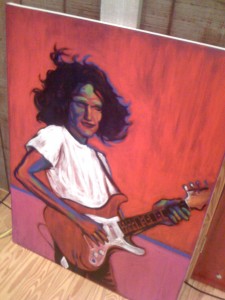

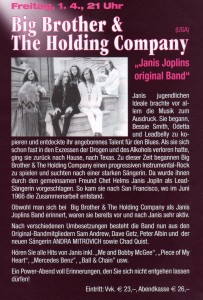

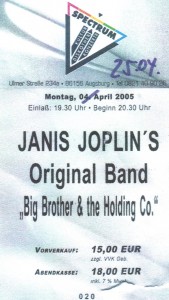

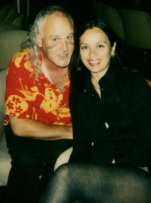

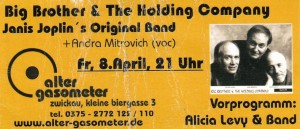

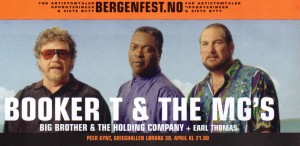

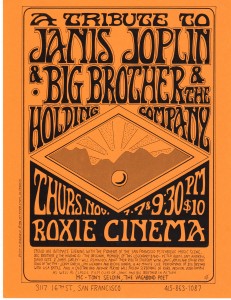

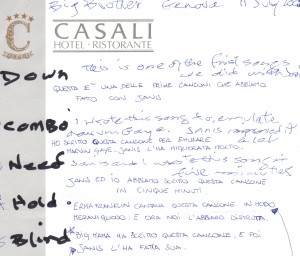

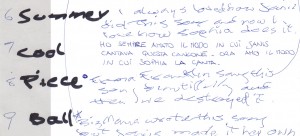

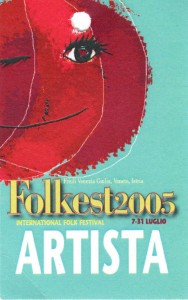

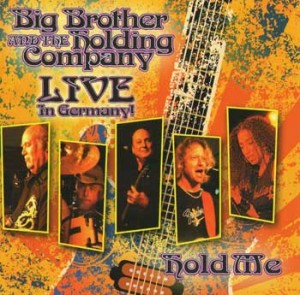

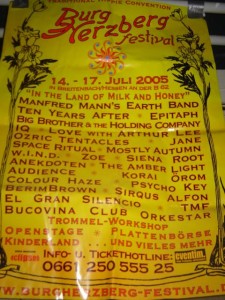

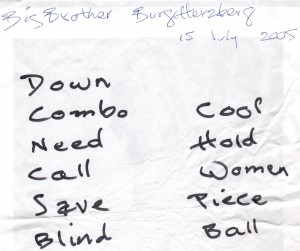

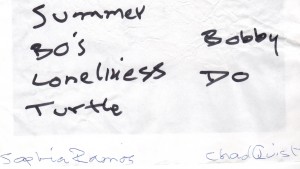

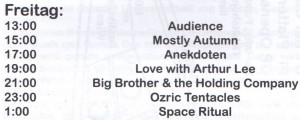

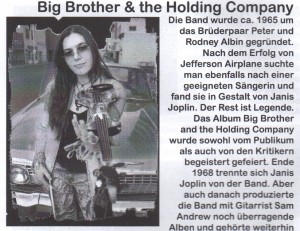

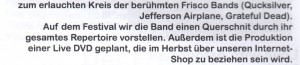

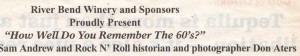

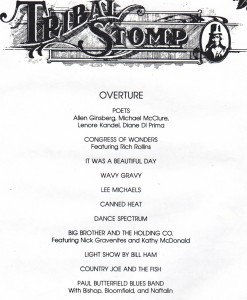

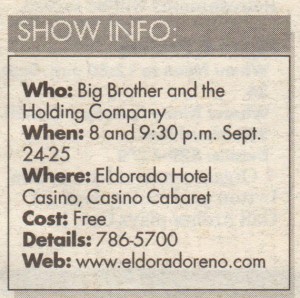

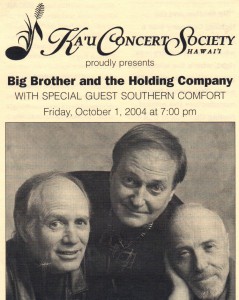

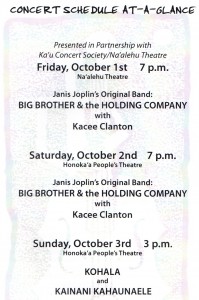

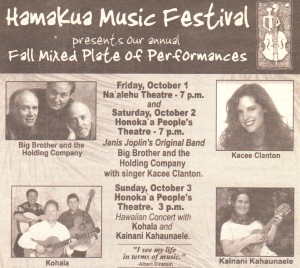

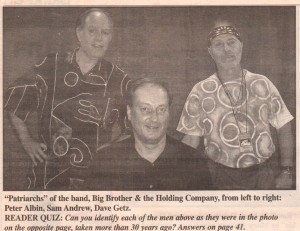

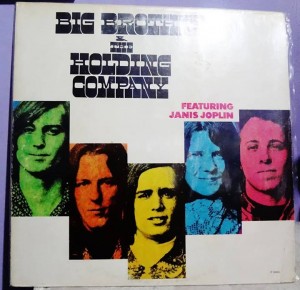

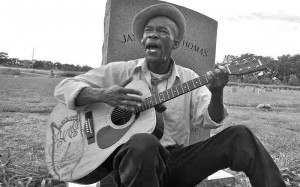

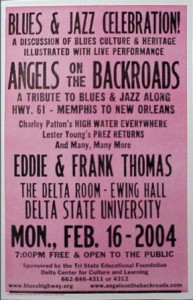

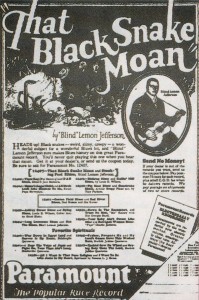

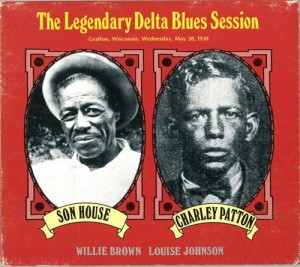

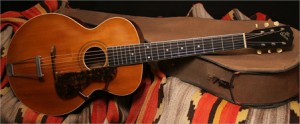

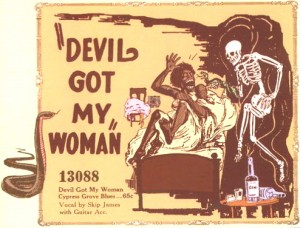

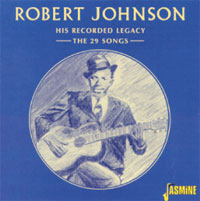

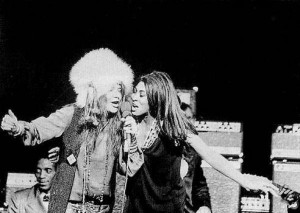

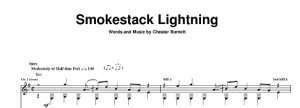

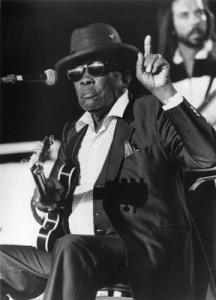

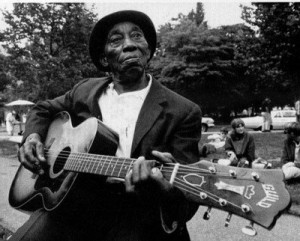

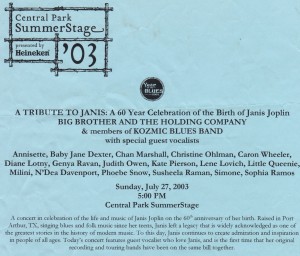

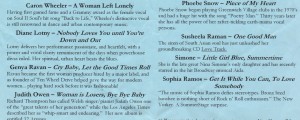

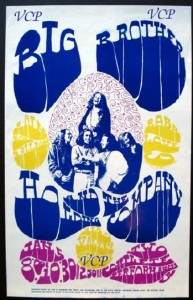

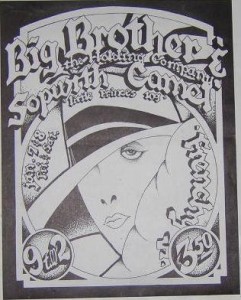

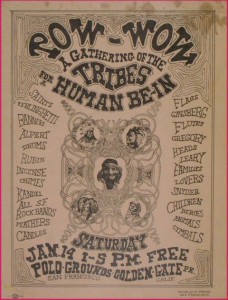

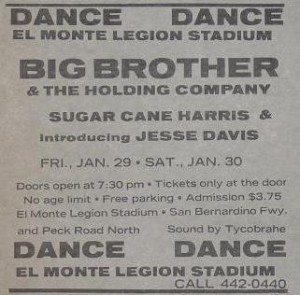

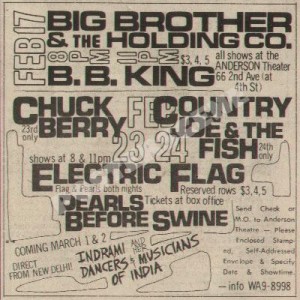

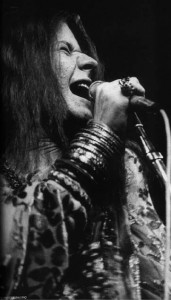

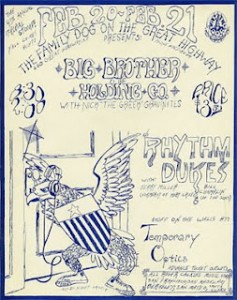

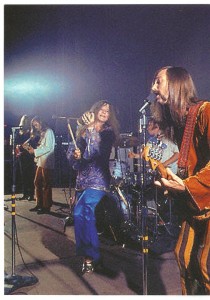

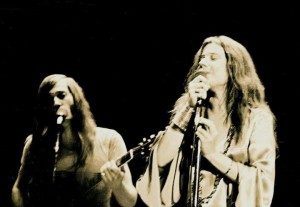

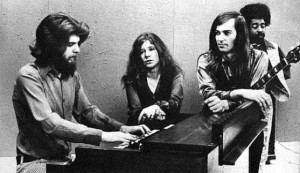

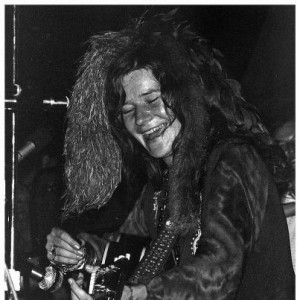

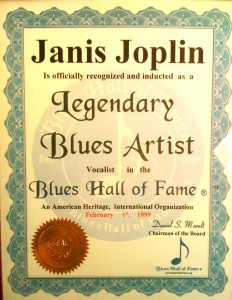

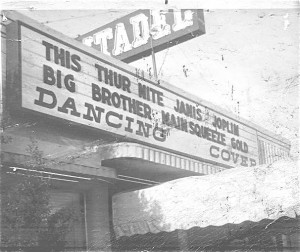

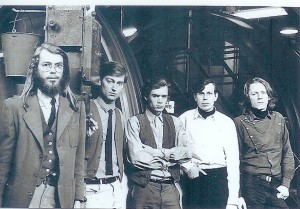

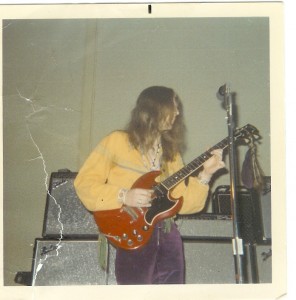

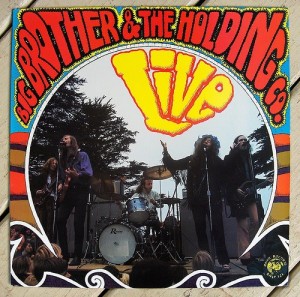

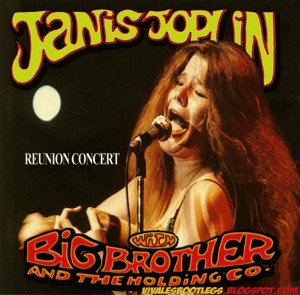

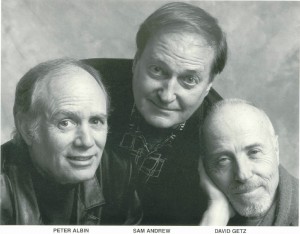

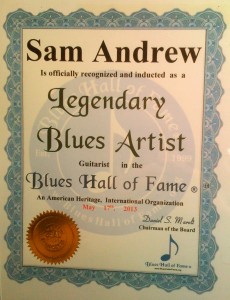

One of the oldest songs in the English language, maybe THE oldest song in the English language is The Cuckoo. Peter Albin and I did The Cuckoo long before there was a Big Brother and the Holding Company, and long after too.

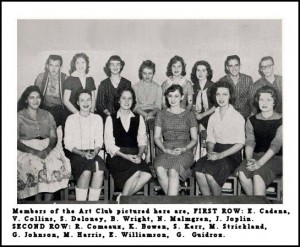

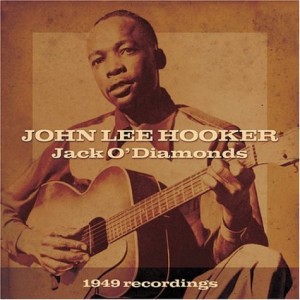

The song finally became Oh, Sweet Mary, but The Cuckoo was long a staple in folk music days. Janis Joplin and James Gurley used to sing the lyrics, which went something like, “Oh, the Cuckoo, she’s a pretty bird, she warbles as she flies, she never hollers cuckoo, til the fourth day of July. Jack of Diamonds, Jack of Diamonds, I’ve known you from of old, you’ve robbed me of my silver, you’ve robbed me of my gold.”

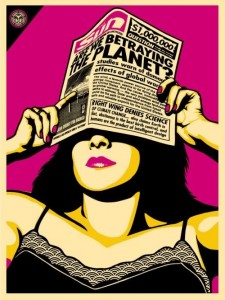

The Cuckoo song is about treachery and betrayal and it is fitting because the cuckoo and her relatives are parasites and traitors, at least viewed from our Judaeo-Christian überconsciousness.

The cuckoo lays her egg(s) in someone else’s nest, the egg then hatches, and ejects the other eggs from the nest.

Now, there is probably no real evil (nor good, for that matter) in the universe, but, if there were, this throwing of the “real” young out of the nest might come close to some kind of evil. This is why the cuckoo became the symbol in ancient folklore for betrayal, treachery and infidelity. Some birds will actually build a new nest bottom over this false progeny and begin their nesting life anew, but most accept the new, huge, ungainly, false offspring, who has killed her “siblings.”

The Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) is the California version of the Cuckoo. Cowbirds deposit their eggs in the nests of over 220 bird species. If the egg is accepted into the brood, the cowbird doesn’t disrupt the family further. But if the egg is rejected, cowbirds trash the nest, destroying the host’s eggs. This brutal behavior led ecologists to dub the species “mafia birds.” Cowbird eggs hatch earlier than host eggs, and although the parasitic hatchling rarely attacks other nestlings, it cries louder, demanding a greater share of the food-which it almost always gets.

This Cowbird behavior frequently leads to the starvation of host nestlings. Here is the problem of Good and Evil nakedly presented. Are we to blame the Cowbird for her behavior? She is acting on instinct. There is no thought, no consciousness here. No free will. Is she “wrong?” Is she “unethical?” Who would posit such a thing? And yet? And yet? If the Brown-headed Cowbird is not evil, then what is? Is “evil” an idea that won’t fit a situation like this? And then, if so, what area would “evil” fit? Adolph Hitler comes to mind. Other very sick people. Allow me to quote myself, “What used to be evil is now a disease.” Such are the lessons of observing nature.

The Western Kingbird (Tyrannus verticalis) has ashy gray and lemon-yellow plumage, and is a familiar summertime sight at our house. This large flycatcher sallies out to capture flying insects from conspicuous perches on trees or utility lines, flashing a black tail with white edges. Western Kingbirds are aggressive and will scold and chase intruders (including Red-tailed Hawks and American Kestrels) with a snapping bill and flared crimson feathers they normally keep hidden under their gray crowns.

Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) build their cup-shaped mud nests almost exclusively on human-made structures. This is a bird of open country which normally uses man-made structures to breed and consequently has spread with human expansion. It builds the nest from mud pellets in barns or similar structures and feeds on insects caught in flight. In England this bird is known simply as the swallow.

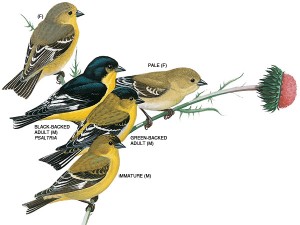

The American Goldfinches (Spinus tristis) are active and acrobatic little finches that cling to weeds and seed socks. Goldfinches fly around here with a bouncy, undulating pattern and often call in flight, drawing attention to themselves. I like the group name for finches, “clarity.” A clarity of finches. It sounds so Elizabethan. My friend Tom Finch and his family are a clarity of Finches. It seems such an appropriate name for them.

Lawrence’s Goldfinches (Carduelis lawrencei) are named after George Lawrence, a New York businessman and ornithologist. The bird was given this name by John Cassin in 1850. This goldfinch feeds on seeds and insects. Their plumage is very beautiful and subtly colored. The female lays 3-6 pale white or pale blue eggs which hatch in 11 to 13 days.

The Lesser Goldfinches (Carduelis psaltria) travel in swiftly moving packs and they like to be on warm south slopes where there is open fresh water.

Lesser Goldfinches will imitate and mimic songs of other birds.

House Finches (Haemorhous mexicanus) are small-bodied finches with fairly large beaks and somewhat long, flat heads. The wings are short, making the tail seem long by comparison.

Many finches have distinctly notched tails, but the House Finch has a relatively shallow notch in its tail.

White-crowned Sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys) are a large sparrow with a small bill and a long tail. The head can look distinctly peaked or smooth and flat, depending on the bird’s attitude. We see White-crowned Sparrows low at the edges of brushy habitat, hopping on the ground or on branches usually below waist level.

The Cedar Waxwing (Bombycilla cedrorum) is, to me, one of the most striking birds on the hectare. They arrive in the fall and winter. The Cedar Waxwing is a medium-sized, sleek bird with a large head, short neck, and short, wide bill. Waxwings have a crest that often lies flat and droops over the back of the head. The wings are broad and pointed, like a starling’s. The tail is fairly short and square-tipped. These birds are so smooth and sculpted that they don’t look quite real.

The Latin/Greek name for the Northern Mockingbird says it all. Mimus polyglottos. Mockingbirds are best known for the habit of some species mimicking the songs of other birds and the sounds of insects and amphibians often loudly and in rapid succession. They can put on displays of calls that they have learned that will rival any concert hall offering.

When I was a boy I was fascinated with these birds and tried to kill as many of them as I could with my BB gun. Such is the insane legacy of testosterone. There were hit songs about mockingbirds, musicians always being fascinated with a fellow songster. Says here (English Wikipedia) that Darwin studied mockingbirds when he was in the Galápagos and not finches. News to me. I would have bet on the finches. On his second voyage he used what he had heard about the tortoises varying from island to island with his data on mockingbirds to buttress his case for the mutability of species.

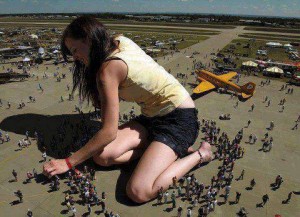

This is a photograph of a University of Florida student being mercilessly harassed by a mockingbird who is protecting her nest, but it reminds me of another species (were they Cedar Waxwings?) at San Francisco State University where I took a graduate course on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales one summer long ago.

When we walked across campus we would be divebombed by birds who had been eating more fermented berries than was strictly wise, and the drunken avians would fly down, tear at our hair, and then make their getaway. They seemed mightily proud of doing this.

This upclose and familiar encounter with the birds was actually most entertaining.

The American Robin (Turdus migratorius) must be the best known American bird, although what an oddly funny Latin name she has. The Robin lays three to five guess what color? eggs in a tree nest made of mud and grass.

This should be our national bird. She is a migratory songster, named after the European Robin because of her reddish-orange breast, though the two species are not closely related, since the European robin belongs to the flycatcher family. Do you find this somewhat disillusioning? I do, but am not sure why.

The American robin belongs to the thrush family.

Some people think that the American Robin ranks behind only the Red-winged Blackbird (and just ahead of the introduced European starling) as the most abundant, extant land bird in North America.

The American Robin is active mostly during the day and assembles in large flocks at night. Her diet consists of invertebrates (such as beetle grubs, earthworms and caterpillars), fruits and berries.

The American Robin is one of the earliest bird species to lay eggs, beginning to breed shortly after returning to its summer range from its winter range. Its nest consists of long coarse grass, twigs, paper, and feathers, and is smeared with mud and often cushioned with grass or other soft materials. It is among the first birds to sing at dawn, and its song consists of several discrete units that are repeated.

Hermit Thrushes (Catharus guttatus) have a chunky shape similar to an American Robin, but smaller. They stand upright, often with the slender, straight bill slightly raised. This is a winter bird.

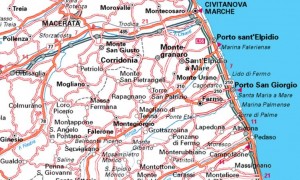

I just saw an article about Swainson’s Thrush (Catharus ustulatus) this morning (8 June 2013) in the Marin Independent Journal.

“A local population of Swainson’s thrushes – a melodic songbird heard along trails and near streams – has had its 1,500-mile-plus migration tracked from Bolinas to Mexico with the use of small tags applied by researchers.”

“The findings could help better protect the habitat of the birds as their lifecycle and travels are better understood, according to Point Blue Conservation Science – formerly the Point Reyes Bird Observatory – which did the research.”

“Until now, all we knew was that these birds likely wintered in Mexico or Central America,” said Renée Cormier, an avian ecologist at Point Blue and lead author of the study. “We’re very excited to finally pinpoint where Swainson’s thrushes spend the winter.”

The Swainson’s Thrushes are distinguished from other spotted thrushes by their eyering and “buffy” face.

Bushtits (Psaltriparus minimus) weave a very unusual hanging nest, shaped like a soft pouch or sock, from moss, spider webs, and grasses. They are fairly plain brown-and-gray birds. Slightly darker above than below, they have brown-gray heads, gray wings, and tan-gray underparts.

The Western Bluebird (Sialia mexicana) is a beautiful, small thrush that often gathers in small flocks to feed on insects or berries, giving their quiet, chortling calls.

Western Bluebirds spread mistletoe seeds and they make us happy. The bluebird of happiness.

It’s always a bit of a shock to see a Mountain Bluebird (Sialia currucoides). They look as if they just flew out of a Disney cartoon because their coloring is so vivid. They will nest up under the eaves of the house or shed, like these lp smartside sheds, because they seem to like human built structures. Sheds are more popular for these birds as they’re not often disturbed, whereas there’s often people in the house. Additionally, if homeowners are keen gardeners and have worms in a compost heap or store birdfood, like suet, mealworms or peanuts in their sheds, the birds will love choose to nest and feast in the shed, compared to the house where they’ll still have to forage for their food.

The Black headed Grosbeak (Pheucticus melanocephalus) is one of the few birds able to eat Monarch butterflies, despite the noxious chemicals those insects contain from eating milkweeds in their larval stage.

These birds visit us most years and even when we can’t see them we hear the young ones who whine and whistle for food.

Western Tanagers (Piranga ludoviciana) are popular at our house because they eat wasps, ants, beetles and termites. They build their nests, usually in coniferous trees, at a fork in the horizontal branch well out from the trunk.

The Western Tanager’s plumage and vocalizations are similar to members of the cardinal family. They sing somewhat like American Robins, but more hoarse. The call sounds like “pit-er-ick.”

Golden-Crowned Kinglets (Regulus satrapa) weigh about as much as two pennies so they are one of the tiniest birds and rather elusive. In Marin County, they breed mostly in Douglas fir and redwoods.

They eat a lot of insects, gnats, caterpillars, aphids and spiders. The female lays a surprising 5 to 11 eggs, sometimes in double layers. The male feeds her while she sits on the nest during incubation.

Early Marin ornithologists weren’t even aware that the Golden-Crowned Kinglet bred here and the birds probably didn’t react well to early logging, but they returned with the regrowth of dense forests. Golden and ruby-crowned kinglets are the only members of their genus in North America, but they are astonishingly similar in appearance and behavior to their two Old World cousins – the goldcrest and firecrest.

We see the Yellow Warbler (Dendroica petechia) fairly often and they were once considered abundant in Marin.

Female Yellow Warblers sing sweet-sweet-sweeter-than-sweet or sweet-sweet-l’m-so-sweet, but males sing various other songs as well, one of them being mean-mean-meaner than mean or mean-machine-I’m so mean. It is rather difficult to write out a bird song even using music notation. Birds’ songs and calls are ineffable and so beautiful. This morning I heard three hawks talking to each other and the conversation was so interesting that I wanted to fly up there myself and say a thing or two about vole catching, an area where I feel they could use a little improvement.

The dreaded cowbird often lays her parasitic eggs in Yellow Warbler nests who thwart these “evil” birds by building a new floor over the cowbird eggs and laying a new clutch of their own. Persistent cowbirds have been known to return five times to lay more eggs in the nest, and the even more persistent warbler builds SIX layers of nest floors to cover up the cowbird eggs. This goes on all the time, whether we are there or not.

Have you ever heard that Latin saying, I think Horace wrote it? It goes Ars est celare artem, and it means it is art to hide art. Keep’em guessing, would be the American vernacular equivalent. Anyway, we now consider the Vermivora celata, the hidden wormeater, otherwise known as the Orange-Crowned Warbler.

Adult male: dusky olive green upperparts, grayer on crown and nape. Whitish or yellowish narrow broken eye ring, indistinct dusky eye line. Greenish yellow underparts with indistinct blurry streaks. Undertail coverts always brighter yellow than belly. Adult female: duller and grayer than male. Immature: duller, similar to adult female. So, where is the orange crown?

The most frequent call is a very distinctive, hard stick or tik. Flight call: a high, thin seet. Song: a high-pitched loose trill becoming louder and faster in the middle, weaker and slower at the end. Birds don’t drawl the way Americans do. An American pronounces “stick” with a bit of a twist. It’s almost like “styi ck,” it’s a lazy diphthong. Birds speak more as British or Continental people do. “Stick,” very short and bitten off to our ears. It’s fast and clipped, virtually without a vowel. “Stck.”

With a length of only 12cm/4.75in, the specific name pusilla (small) given to Wilson’s Warbler (Wilsonia pusilla) by Alexander Wilson in 1811 is appropriate.

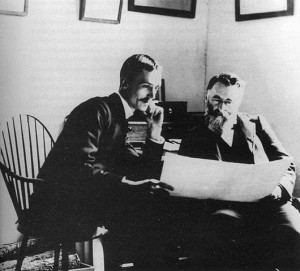

Alexander Wilson moved from Scotland to Pennsylvania in 1794 at the age of 28, became interested in ornithology in 1801 and decided in 1802 to publish a book illustrating all the North America birds. This appeared as the nine volume American Ornithology between 1808 and 1814.

Wilson met John James Audubon in 1810 and probably inspired him to publish his own book of illustrations, even though Audubon’s reaction to Wilson is described as ‘decidedly ambiguous’. (He declined to subscribe to American Ornithology, felt his own illustrations were much better and, in 1820, decided to publish the ‘greatest bird book ever’.)

This bird is quite small and will fit in the palm of your hand with room to spare. Occasionally I see the females down by our creek in the underbrush, so little that I think at first that they are flies. How can you fit all that life into such a diminutive package?

The Violet-green Swallow (Tachycineta thalassina) is a truly beautiful bird and the only swallow that lives in the woodlands and forests of Marin County. The purple on the upper-tail coverts, often not seen, identifies this as a male. Green on the back can be bright in both sexes, male head usually relatively bright green; female head duller green to brownish. The extension of white above the eye is a mark that allows distinction of Violet-green from Tree Swallows in flight. The two species co-exist in the San Francisco Bay Area, with the Violet-green usually at higher altitudes and the Tree more often near bodies of water

These swallows will find old woodpecker holes or natural cavities in trees for nest sites, and they will also use nest boxes or crevices in buildings.

Swallows catch insects in flight. They have a short, wide bill that opens into a gaping mouth ideal for scooping up prey in mid-air.

The Violet-green Swallows are winter birds. They arrive sometimes as early as mid-January. They get along well with other swallows and add some much needed color in the cold months.

I see other birds here on the Piliwale Andrew hectare, but I don’t know what they are and need to take a good photograph for identification. Birds are singers and travelers, so we feel a lot of kinship with them. See you next week.

______________________________________