During May and June of 1901 and 1902 I was engaged in excavating for the Peabody Museum of Harvard University a mound in Coahama County, northern Mississippi.

At these times we had some opportunity of observing the Negroes and their ways at close range, as we lived in tent or cabin very much as do the rest of the small farmers and laborers, white and black, of the district.

Busy archaeologically, we had not very much time left for folk-lore, in itself of not easy excavation, but willy-nilly our ears were beset with an abundance of ethnological material in song, words and music.

In spite of faulty memory and musical incompetency, what follows, collected by Mr. Farabee and myself, may perhaps be accepted as notes, suggestions for future study in classification, and incidents of interest in the recollecting, possibly in the telling.

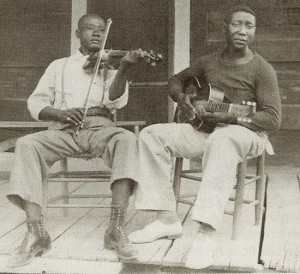

The music of the Negroes we listened to may be put under three heads: the songs sung by our men when at work digging or wheeling on the mound, unaccompanied; the songs of these same men at quarters or on the march, with guitar accompaniment; and the songs, unaccompanied, of the indigenous Negroes, indigenous opposed to our men imported from Clarksdale, fifteen miles distant.

Most of the noise of the township was caused by our men, nine to fifteen in number, at their work.

On their beginning a trench at the surface the woods for a day would echo their yelling with faithfulness.

The next day or two these artists being, like the Bayreuth orchestra, sunk out of sight, there would arise from behind the dump heap a not unwholesome mugmós as of the quiescent Furies.

Of course this singing assisted the physical labor in the same way as that of sailors tugging ropes or soldiers invited to march by drum and band.

They tell, in fact, of a famous singer besought by his co-workers not to sing a particular song, for it made them work too hard, and a singer of good voice and endurance is sometimes hired for the very purpose of arousing and keeping up the energy of labor.

This singing in the trenches may be subdivided into melodic and rhythmic: the melodic into sacred and profane, the rhythmic into general and apposite.

Our men had equal penchants for hymns and “ragtime.”

The Methodist hymns sung on Sundays were repeated in unhappy strains, often lead by one as choragus, with a refrain in “tutti,” hymns of the most doleful import.

Rapid changes were made from these to “ragtime” melodies of which “Molly Brown” and “Goo-goo Eyes” were great favorites.

Undoubtedly picked up from passing theatrical troupes, the “ragtime” sung for us quite inverted the theory of its origin.

These syncopated melodies, sung or whistled, generally in strict tempo, kept up hour after hour a not ineffective rhythm, which we decidedly should have missed had it been absent.

More interesting humanly were the distichs and improvisations in rhythm more or less phrased sung to an intoning more or less approaching melody.

These ditties and distichs were either of a general application referring to manners, customs, and events of Negro life or of special appositeness improvised on the spur of the moment on a topic then interesting.

Improvising sometimes occurred in the general class, but it was more likely to be merely a variation of some one sentiment.

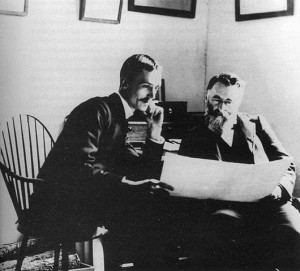

This tantalizing report was written by Charles Peabody, an archeologist at Harvard, and one can only wish that there would have been some followup studies at that time on the music in the Mississippi Delta.

Charles Peabody and his team may have heard the earliest forms of Delta blues.

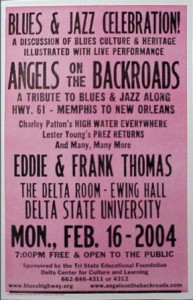

My wfie Elise Wainani Piliwale studied at Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi. She tells me stories about Delta blues.

Twenty years before Elise, another person dear to me, Bill Ham, father of the modern light show, attended Delta State because, he said, it was the only school in his area to offer an art major.

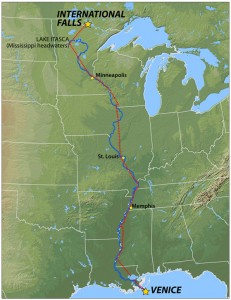

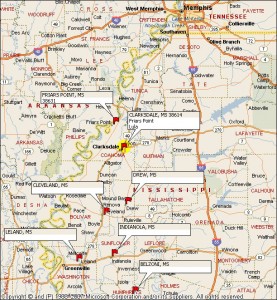

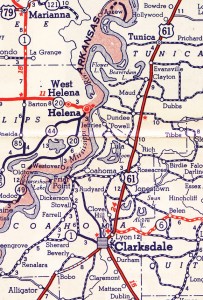

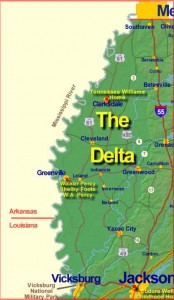

The Delta is a flat, very flat alluvial plain and it must have been the real delta once, the place where the Mississippi emptied into the Gulf of Mexico, but the river has brought so much soil from the rest of the country down here that her mouth is now far to the south.

Frances (Fanny) Kemble wrote Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation 1838-1839. She is a sharp observer and her story is of great interest as a kind of prelude to the narrative of life in the Delta.

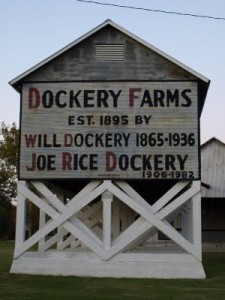

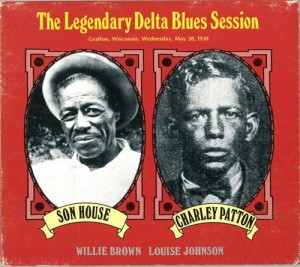

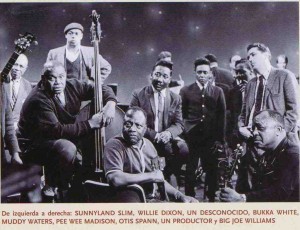

Dockery Plantation was wrested from the Mississippi mud around 1895 by Will Dockery. It had a post office, a commissary and a cotton gin. Many blues people spent time here, among them one of the first, Charley Patton, who mentored Robert Johnson, Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King and Muddy Waters.

Parchman Farm, the Mississippi state penitentiary for men, was part plantation, part prison. Booker (Bukka) White spent time here and wrote Parchman Farm Blues. Alan Lomax made many recordings here for the Library of Congress.

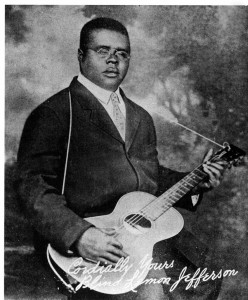

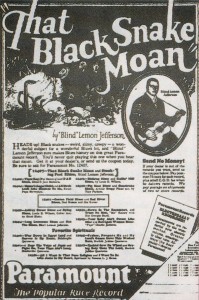

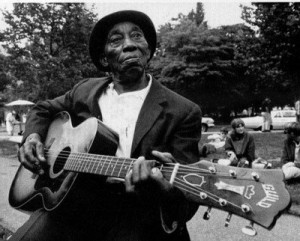

Although Blind Lemon Jefferson (1893-1929) was born south of Dallas near Wortham, Texas, and he has a distinct Texas sound in his voice, he spent much of his life in the Delta.

Howlin’ Wolf remembered seeing Blind Lemon in Mississippi in 1926, the same year he first saw Charley Patton.

Jefferson was very well liked in the Delta, where everyone tried to copy him.

Black Snake Moan shows Blind Lemon’s great voice and it was very popular in the Delta. The song is in C and the guitar playing is very good, fluid, in good time and most interesting.

Blind Lemon goes to an A (minor) before playing G, rather unusual in this style. It’s a twelve bar blues but he leaves in an extra measure here and there, so the form becomes a 14 bar frequently. The playing is very pentatonic.

A word here about keys. These recordings are almost a hundred years old now and tuning could be an arbitrary process, then and now.

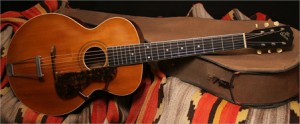

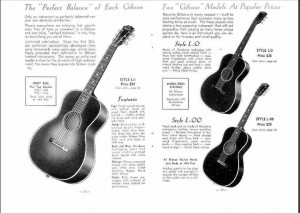

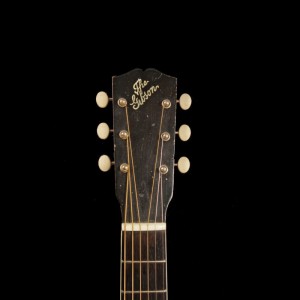

Also the Delta blues people used different tunings such as DADFAD for the guitar low to high (Skip James) or open G, also called “Spanish” tuning DGDGBD (Charley Patton, Robert Johnson and many others).

And then some players would tune down a whole tone and put the capo on the second fret, so it’s not like we’re hearing a piano or a harmonica where the tuning is set. On the guitar as on all the stringed instruments the tuning can easily be wandering and imperfect.

Blind Lemon’s skillful guitar playing and impressive vocal range influenced Furry Lewis, Charlie Patton, Barbecue Bob and many other players up to the present time.

Ralph Lembo, a Sicilian-born dry goods salesman who owned a furniture store in Itta Bena, Mississippi, arranged for Jefferson to play in his store. Lembo charged customers 25¢ admission for a view of the artist, but after three hours of playing music Blind Lemon refused to continue because the money didn’t look good.

Another financial dispute marred his performance at Itta Bena’s Rolling Wall High School: ‘They had a big dance there and Lemon come in and play, and they was chargin’ 75¢ to come in,’ David Edwards recalled. ‘That was a lot of money then, and they couldn’t get him to play for that 75¢.’” Lembo’s attempt to pair Blind Lemon Jefferson and Charley Patton at a recording session also failed.

One Dime Blues is a fun tune to play on the guitar, but it’s difficult to play it as fast and fluid as Blind Lemon does.

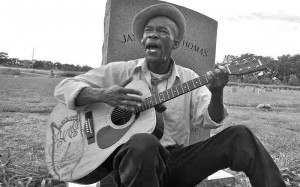

See That My Grave Is Kept Clean is in E and everyone has done this song, including me. Lemon had a great voice, two octave range, and he sang in a clear, high style.

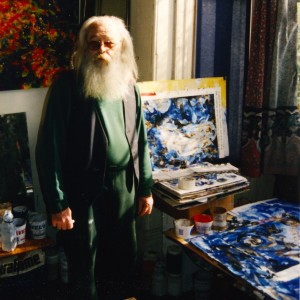

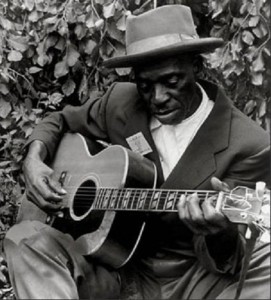

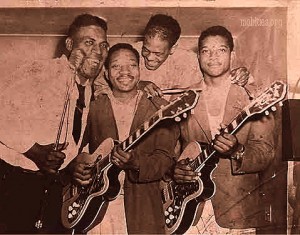

Charley Patton lived most of his life on Dockery Plantation. He was a small man, maybe five feet seven and weighing 135 pounds, but when he began to sing, his voice was strong and clear. Howlin’ Wolf said he had the voice of a lion. It was not only low, but wide and very clear. It was very strange to hear that big voice coming out of that little man.

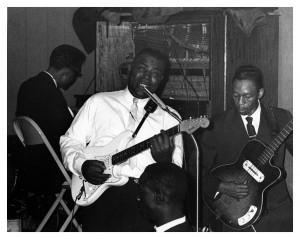

Charley Patton had a large bag of showman’s tricks, theatrics, clowning, playing the guitar behind his back, between his legs. This is his youngest daughter Rosetta holding his portrait.

Charley Patton plays Spoonful Blues in the “Spanish” tuning DGDGBD with the capo on the second fret. He plays the guitar in his lap. The chord outline is very unusual and interesting. There is a little intro in E and then he goes to C# F# B E. Patton’s use of the bottleneck has a lot of vibrato and expression. He makes the guitar sound like a voice.

Charley Jordan plays Spoonful in G (so G E A D G) and does a good job. Mississippi John Hurt’s version is characteristically mellow, soft, kind. Comparing his version with Charley Patton’s tells you a lot about both men.

Patton’s Spoonful is about drug addiction and murder. Mississippi John Hurt’s is a love song. And they’re both singing the same song!

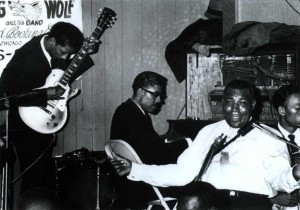

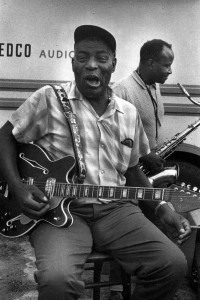

Howlin’ Wolf’s Spoonful, a different song entirely, is a love song too, come to think of it. That’s a regular sized guitar that Wolf’s playing. He was a giant, in more ways than one.

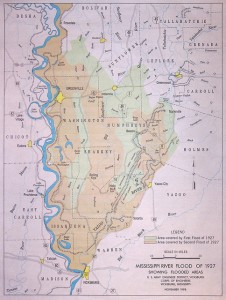

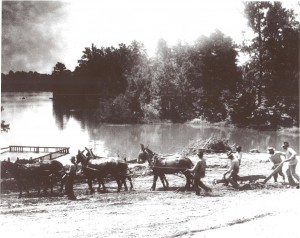

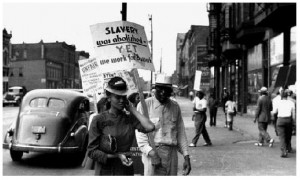

Charley Patton’s High Water Everywhere is the story of the 1927 Mississippi flood, a terrible event, that was a contributing factor in the Northern Migration (1920s) of black people to places like Detroit, Chicago, New York, Oakland where they started new lives and new blues styles.

High Water Everywhere is done in two parts and the guitar is tuned DGDGBD, open G tuning, “Spanish” tuning. A capo is put on the third fret so that it becomes an open Bb tuning.

He’s hitting the guitar, he’s stomping on the floor and he’s shouting and hollering. There is a very strong percussive feeling of tragedy and despair.

This was an area of land the size of New England, and it was flooded for five months.

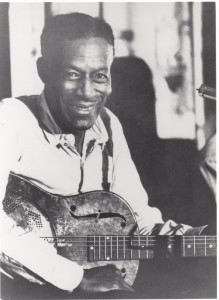

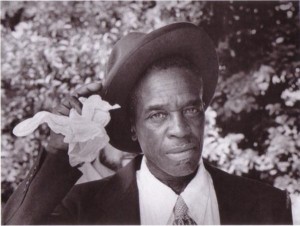

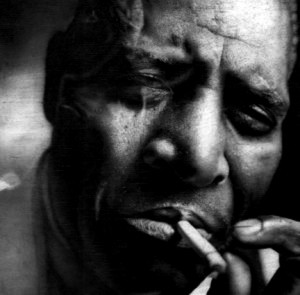

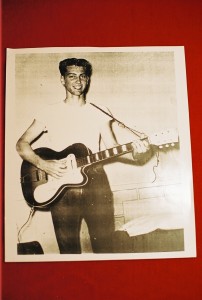

This is a man who looked like this and sang like something else entirely.

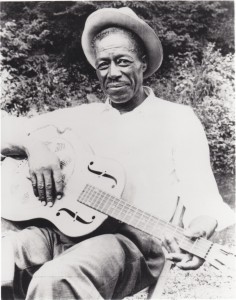

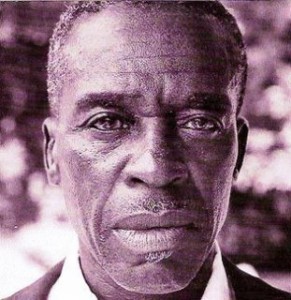

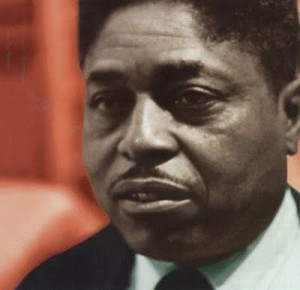

Eddie James “Son” House, Jr. (1902-1988) sang Clarksdale Moan. He was a preacher and pastor for years, but at 25 he became a blues man.

In a short career interrupted by a spell in Parchman Farm penitentiary, Son House developed to the point that Charley Patton deigned to invite Son House to share engagements, and to accompany him to a 1930 recording session for Paramount Records.

Their records, issued with perfect blues timing at the beginning of the Depression, did not sell and did not lead to national recognition for either musician.

Son was popular, and in the 1930s, together with Willie Brown, he was the leading musician of Coahama County.

Son House had a big influence on a lot of people, including Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters.

In 1941 and 1942, House and the members of his band were recorded by Alan Lomax and John W. Work for Yale and Fisk University. The following year, Son House left the Delta for Rochester, New York and gave up music.

In 1964, a group of young white record collectors (including the great harmonica player Al Wilson) discovered House, whom they knew of from his records issued by Paramount and by the Library of Congress.

With their encouragement, he relearned his style and repertoire and enjoyed a career as an entertainer to young white audiences in the coffee houses, folk festivals and concert tours of the American Folk Music Revival, so he was now a folk singer.

He still played with his old strength and wild abandon, especially with his right hand which flailed and thrashed across the guitar in such songs as Death Letter Blues which features a classic Delta riff beautifully played.

Son House recorded several albums, and some informally taped concerts have also been issued as albums. He died in 1988.

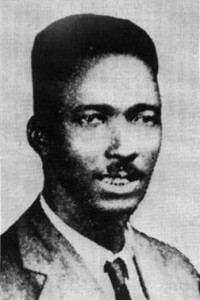

Tommy Johnson and Charley Patton were from Drew, Mississippi (so was Roebuck Staples). Patton was loud, strong and passionate, but Tommy Johnson was probably the better guitar player with a rock steady sense of rhythm.

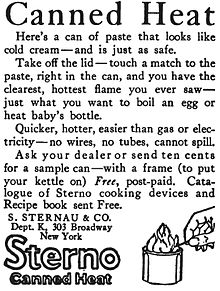

Johnson recorded Canned Heat Blues in 1928, telling about his struggles with alcohol addiction.

Sterno was popular during the Great Depression in hobo camps, or “jungles”, when the Sterno would be squeezed through cheesecloth or a sock and the resulting liquid mixed with fruit juice to make “Jungle Juice” or “Squeeze”. I remember finding cans of this stuff near railroad tracks when I was a boy.

They didn’t use it for cooking; they used it for the methanol and ethanol it contained.

On Canned Heat Blues, Tommy Johnson plays a guitar part in D that every rock and roll player will recognize, a very steady boogie beat, and he sings in a voice that slips easily into falsetto, a beautiful blues that is very soulful, telling about his self destructive streak.

Tommy Johnson had much more talent than fame or riches. He was not the first nor the last to have that distinction.

Tommy Johnson was born around 1896 and he died 1956 in Crystal Springs, Mississippi.

He was the first Delta musician to claim that his talent had come from selling his soul to the devil.

Robert Johnson would later, and more famously, make the same claim. Playing and practicing a lot probably had something to do with these musicians’ prodigious development too. The devil was no joke in Mississippi in the 1920s, though.

Tommy Johnson had a stutter and a lisp. H.C. Speir who was recording him said he sounded like a snake, but when Johnson began to sing, as is so often the case with vocalists and their speech defects, the stutter and lisp disappeared immediately, and a strong, confident voice took over.

Cool Drink of Water Blues is in F and it shows Johnson as a master singer sliding up into a high yodel that Jimmie Rodgers must have heard. “I asked her for water and she gave me gasoline.” Great singing, great playing.

“People’d walk five or six or ten miles to hear him, if they heard he was gon’ be in town,” says Houston Stackhouse, a guitar player, “They’d say, ‘Tommy Johnson’s in town! Got to go hear Tommy’ Yeah, he’d draw a crowd, man….They’d block the streets.”

I love these Delta blues and always have since I knew what they were. People like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton, Son House, Tommy Johnson, Willie Brown, Ishmon Bracey, Kid Bailey, Arthur Crudup, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, B.B. King, Jimmy Reed, Howlin’ Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt, Furry Lewis, they all play such great music.

Think of all the ones that we don’t know, because it is so hit and miss, so accidental the ones who survived on records for us to hear. Whom did we miss? So many, probably most of the great players have died unheard of and in oblivion.

My grandfather on my mother’s side was only one of many, many people who sat out in the dark playing after a hard day in the fields playing their beautiful pure music. Stomping, giving life to these songs, as old as life itself. I remember them all in vivid detail. Old songs from the olden time.

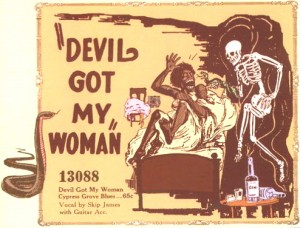

All of these songs stay with me, but two of them are particularly haunting, Geeshie Wiley’s Last Kind Words and Skip James’ Devil Got My Woman.

Geeshie Wiley was from Natchez, Mississippi, according to Ishmon Bracey.

She played guitar on Elvie Thomas’ Motherless Child Blues, an unusual 16 bar blues (the first line is sung three times).

Last Kind Words doesn’t have the usual 12 bar structure but it is a real blues in feeling, a very beautiful and even mystical song. The key is E but the first chord for the vocal is A minor and she sings the C in that chord. Her playing and singing are very relaxed. She doesn’t push. The music and words just seem to pour out slowly.

The last kind word I heard my daddy say, Lord, the last kind word I heard my daddy say, If I die, if I die in the German war, I want you to send my body, send it to my mother, Lord. If I get killed, if I get killed, please don’t bury my soul, I say just leave me out, let the buzzards eat me whole…

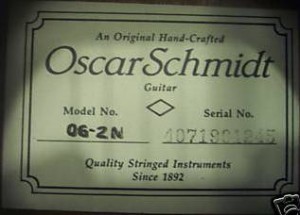

Skip James tuned his guitar to DADFAD or EBEGBE. It doesn’t matter really since they are both the same. It’s an open minor tuning and it depends on whether you use a capo at the second fret or not. If you tune it DADFAD and put a capo on the second fret, it’s going to be EBEGBE.

Most of the Delta people who used another tuning besides standard, tuned in the “Spanish” manner (open G), that is DGDGBD which has a major feeling, so James DADFAD tuning is minor and haunting already and then when his voice comes out, there is just nothing like it.

Skip James had married Oscella Robinson, a preacher’s daughter, educated and from a good family. He and Oscella moved to Texas, where she deserted him to be with a World War I veteran. James was grief stricken and he had thoughts of suicide and violent revenge. He didn’t remarry for twenty years. The result of this was one of the most amazing songs ever written, Devil Got My Woman.

I’d rather be the devil, to be that woman man. I’d rather be the devil, to be that woman man. Aw, nothin’ but the devil, changed my baby’s mind. Was nothin’ but the devil, changed my baby’s mind. I laid down last night, laid down last night. I laid down last night, tried to take my rest. My mind got to ramblin’, like wild geese from the west, from the west…

In Terry Zwigoff’s wonderful film, Ghost World, Enid (Thora Birch) asks the record collector (Steve Buscemi), “Where can I get other records like this?” He replies, “There are no other records like this,” which is exactly right.

On Devil Got My Woman, Skip James is playing in D minor (tuning DADFAD). After a short introduction he begins the tune in the dominant (A minor) in a high, eerie, lonesome voice. This is just not like any other singing that I know of. As with all great art, it scares you, it’s coming from somewhere else.

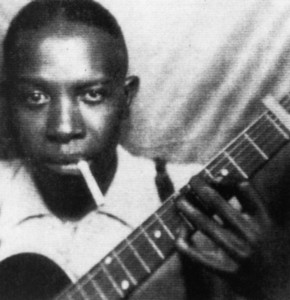

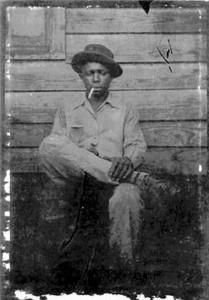

Robert Johnson (1911-1938) studied the music of Skip James and always returned to it as a source of inspiration.

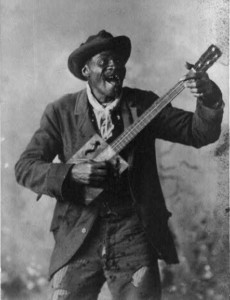

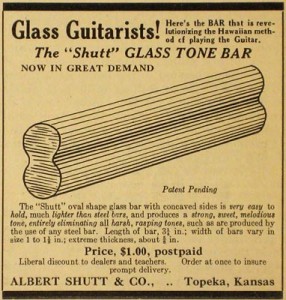

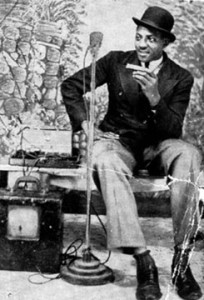

Johnson played the harmonica, the jaw harp and the diddley bow long before he picked up a guitar. To make a diddley bow, you could drive two nails into a plank, tie some wire to them, broom wire, cotton baling wire. Then, for a bridge, you could shove a piece of wood or an empty can under the wire and then play the contraption with some kind of slide, a bottle neck, a piece of metal, anything that would slide along the strings.

If you reverse the words “diddley bow,” you get Bo Diddley. He played one, Howlin’ Wolf did, B.B. King did, many people played the diddley bow.

Probably every child experiments with some kind of arrangement like this at some time, even if it’s just rubber bands stretched across a box.

When Robert Johnson arrived in a new town, he would play for tips on street corners or in front of the local barbershop or a restaurant.

Johnny Shines and other musicians have noted that Johnson didn’t play his dark blues pieces in situations like these, but instead pleased audiences by performing more well-known pop standards of the day.

He could pick up tunes at first hearing and so had no trouble giving his audiences what they wanted, especially since he liked jazz and country music.

Robert Johnson could quickly establish a rapport with his audience. He made new friends easily and established ties to the local community that would serve him well when he passed through again a month or a year later.

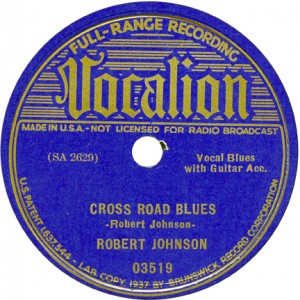

To play Cross Road Blues, Robert Johnson tuned to an open G (Spanish tuning) DGDGBD.

Then he put a capo on the third fret, which gave him an open Bb.

Johnson recorded Terraplane Blues in San Antonio in 1936.

He did this one in Bb too. After playing these two tunes in Bb, it’s a real relief to go into standard tuning and do them in A, as Roy Rogers does.

Similarly, one way of looking at Love In Vain is to imagine Robert Johnson playing in the ordinary tuning for guitar EADGBE and doing the tune in A. If you’ve been playing in Bb for a while and trying to imitate an open G tuning in your regular tuning, you’ll feel like a genius when you play Love In Vain in A, standard tuning.

I like the way Robert Johnson sings this Love In Vain, so easy and relaxed, and the guitar playing is subtle and perfectly matched to the vocal.

Well, the train left the station, with two lights on behind. The blue light was my blues, and the red light was my mind.

Some people play Love In Vain with an open G tuning, capo on the first fret, and that sounds good too. It puts the song in Ab.

You could make a good case that that is the way Robert Johnson did the tune, but the A in standard tuning is very tempting also. Both ways are good. There’s James Joyce playing the guitar. I’m not sure what key he used for Love In Vain, but I notice he’s not using a capo.

Preaching Blues (Up Jumped The Devil) is in E and it shows the energetic, inspired Robert Johnson who played guitar marvelously well.

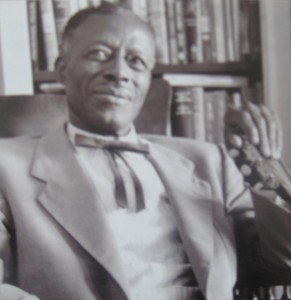

This is Henry Saint Clair Fredericks (Taj Mahal). I have heard him play several Robert Johnson tunes, including Preaching Blues.

Preaching Blues aside from featuring Robert Johnson’s strong singing is an encyclopedia of blues riffs for the guitar. He uses his thumb to hit the guitar top percussively between each chord that he plays with his three (not two) fingers. The main riff of the tune is E D G-E high to low.

Robert Johnson plays a lot of minor 2nds. That is, he strikes, for example, an F# note right next to an open G. This is a very strong sound on all the stringed instruments. On a violin, it’ll make your hair stand on end. It’s a good idea to look for these combinations all over your fingerboard.

Son House was often called a mentor to Robert Johnson but Son House didn’t see it that way. He saw Robert Johnson as a pesky interloper to be swatted as one would swat a mosquito. “Such another racket you never heard. It’d make people mad, you know. They’d come out and say, ‘Why don’t y’all go in there and get that guitar away from that boy! He’s running people crazy with it.’ I’d come back in and I’d scold him about it. ‘Don’t do that, Robert. You drive the people nuts. You can’t play nothing.’”

Some people quit when they hear things like this. Other people just grit their teeth, go ahead and keep playing. It’s a painful Darwinian process. I’ve had to live through it many times. It never gets easier.

When they show this learning process in films, it is always depicted as a momentary defeat and then comes a GLORIOUS TRIUMPH, but it doesn’t feel that way in real life. In real life, the defeat part can last a long time and the triumph part can seem very short lived, beside the point and inconsequential when it finally comes.

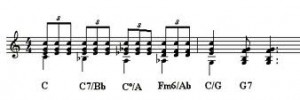

Musicians call this a turnaround, a short piece of material that goes between two verses. This is a typical Robert Johnson turnaround, although he more often began on the Bb (fourth string, 8th fret) while he was playing that top C, and then played Bb A Ab G (F F# G).

Robert Johnson plays Ramblin’ On My Mind in E and sometimes in D and his voice is so good on the tune. He sweeps up on the guitar often on the upbeat which makes for a strong rhythm. Roy Rogers, the master slide guitarist, not the cowboy, plays Ramblin’ in D and has a lot of illuminating things to say about Robert Johnson. That upbeat sweep across all six strings is the thing, though. Try that.

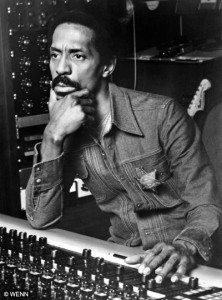

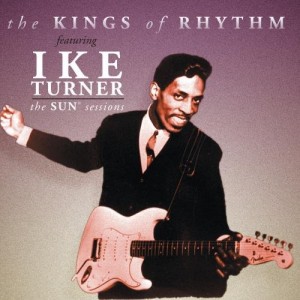

Something that may surprise people a great deal is that Ike Turner was a real live Delta blues musician. He was born in Clarksdale, Mississippi, and he knew how to play the blues in that Delta way, knew all the tricks in many styles.

Sam Cooke, another man who made the transition from Delta blues to pop stylings was also from Clarksdale.

Ike Turner was not only an accomplished guitarist in many different styles, but he also was, obviously, an entrepreneur and a person who made things happen for a lot of people.

Sam Cooke was a gospel singer, a very good gospel singer, and then he went to write a lot of songs in a distinctly pop style.

As I have noted elsewhere, there are two or three or four sides to every story, and I wish my life would have been blameless so far, but far, far from it. Anyway, we in Big Brother and the Holding Company knew Ike and Tina well and we did a recording session with them, Kathi McDonald singing. Let’s see, James passed out beneath my chair, so Dave the drummer got up and left the session. As usual, Peter and I kept playing. We finally got a drummer from Berkeley. I would like to find that guy today and ask him his impressions of that surreal afternoon in the studio, because that was a moment. It was definitely a moment.

Ike said, “Who these guys think they are, the fucking Beatles?” a not irrelevant question given our stellar performance in the studio that day. Tina was sitting there at the console, looking very regal and taking it all in. I would love to find the tapes of that session.

Anyway, Ike brought many people to fame and he helped them in substantive ways too. He booked their studio time and took his whole band into the studio to back them up and make them sound good.

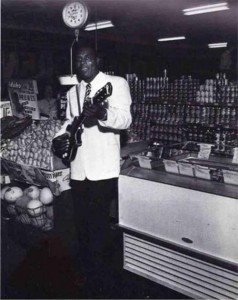

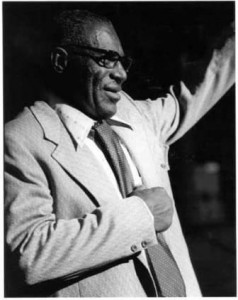

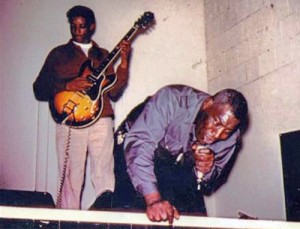

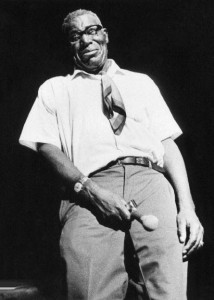

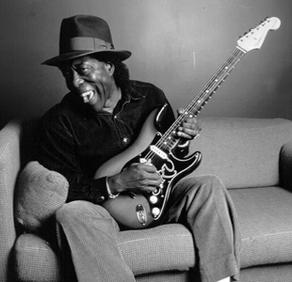

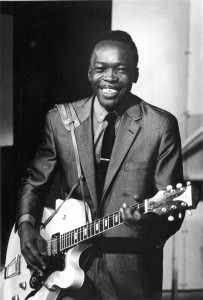

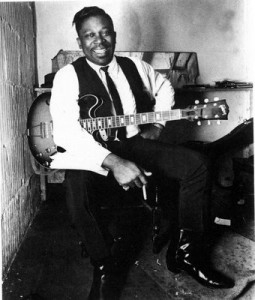

Ike told Sam Phillips at Sun Records about Chester Burnett, thus doing Sam, Chester and all of us a big favor, since Chester Burnett (Howlin’ Wolf) would go on to make great music. I see Wolf is giving this guitar to Kerry Kearney.

Rocket 88 was credited to a local man, Jackie Brentson, but the man behind it all was Ike Turner, another Clarksdale transplant, who took a standard blues, put in a fat backbeat, added some fuzz, maybe from damage to the amp while driving down 61 to Memfus (Memphis), and, with all of that, came out with the number two rhythm and blues song in 1951.

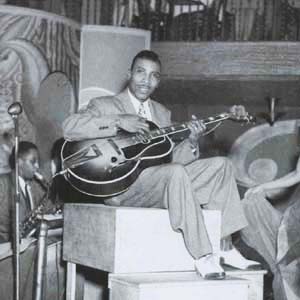

Ike Turner alerted the Bihari brothers, owners of Modern Records, to the up and coming B.B. King, who was making a name in the Memphis area.

Ike Turner played piano and guitar on many of these “audition” tunes and did everything he could to help these newcomers.

Many of these recording sessions took place at The Memphis Recording Service (Sun Records) at 706 Union Avenue, a former radiator repair shop, that still looks more or less like a radiator repair shop.

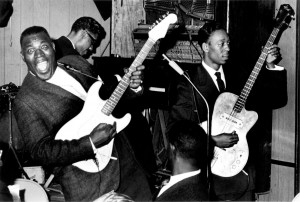

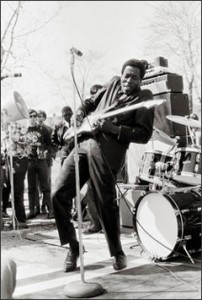

Ike Turner had told Sam Phillips about Chester Burnett who walked into the studio in the summer of 1951, and Sam had heard Burnett’s voice on the radio, but he wasn’t ready for the man’s physical appearance. Howlin’ Wolf (Burnett’s stage name) was over six and a half feet tall and he stood on two of the biggest feet that Phillips had ever seen.

I had the same reaction to Wolf when I saw him sitting by a pool table playing his blues in Chicago 1966. Even sitting down he was a giant and he wore white socks which seemed further to exaggerate the size of his feet.

“I tell you, the greatest thing you could see to this day would be Chester Burnett doing one of those sessions in my studio. God, what it would be worth to see the fervor in that man’s face when he sang…How different, how good!” Sam Phillips said that Wolf was the most talented man who had ever walked through the doors of Sun Records. I believe that. It’s easy to believe.

Howlin’ Wolf was born two hundred miles south of Sun Records in White Station, Mississippi, two hundred miles and a universe away. His early life reads like a Dickens story, abject poverty, medieval working conditions, indifference and cruelty on all sides. How he kept his positive and even glowing attitude and his strength of spirit is one of the inspiring stories of the human condition.

He used to forage barefoot for scraps of food down by the railroad tracks where he hoped the workers might have left something behind. He couldn’t read nor write nor do the most basic figuring even by the time he reached Sun Records. He could run, run away from whippings and beatings, and yet he grew to be a man who went to night school, even at the height of his success, and who kept learning all his life, an eternal student.

His father was a sharecropper and his mother was a cook and a maid. He was born 10 June, 1910, which made him much older than Ike Turner, B.B. King, John Lee Hooker and others who had achieved success before him. Howlin’ Wolf was more like a contemporary of Charley Patton or Robert Johnson, and his voice seemed to come from long ago and far away. He was called Bigfoot, Foots, Buford, Bullcow and Wolf, from Little Red Riding Hood, Wolf to scare him.

His mother Gertrude Jones sang songs on the street and took her son to sing in the church choir. She abandoned her son when he was a young child because he was dark, he sang the blues, because he didn’t want to work in the fields for fifteen cents a day, because she had a new man who didn’t want a boy in the house, so he went to live with a mean uncle who whipped him with a plow line and made him take his meals apart from the family.

He was sad, but he could sing. He sang loudly when he plowed the fields, sang all day, made up songs. He had his instruments too, a tin bucket, a diddley bow that he made himself, pots and pans, a fifteen cent harmonica. In 1928 when he was seventeen, Wolf got his first guitar and Charley Patton helped him learn how to play it and showed him how to be a performer.

Wolf began playing at house parties, juke joints and street corners and even crossed the river to play in Arkansas at Pine Bluff, Brinkley or West Memphis, a rough wide open town. Johnny Shines who saw him at this time says, “I was afraid of Wolf. Just like you would be of some beast or something. It wasn’t his size. I mean, what he was doing, the way he was doing, I mean the sound he was giving off. That’s how great I thought he was.”

Sonny Boy Williamson II (Aleck Ford Rice Miller) finished Wolf’s schooling on the harmonica. Howlin’ Wolf traveled with Robert Johnson and played with Son House and Willie Brown. He also worked with Johnny Shines, Jimmy Rogers, Honeyboy Edwards, so his musical education was deep and varied.

When World War II came, Howlin’ Wolf went into my father’s outfit, the Signal Corps, where he was to learn radio communication as a Technician Fifth Grade, but this didn’t really work out for him.

He was hospitalized in Portland, Oregon, for dizziness and physical exhaustion and his violent outbursts resulted in an Honorable Discharge, on 3 November 1943.

Wolf moved to West Memphis and formed a band, the House Rockers: Willie Johnson, piano; M.T. Murphy, guitar; Junior Parker, harmonica and Willie Steele, drums. Sometimes James Cotton would join the group. Howlin’ Wolf bought his first electric guitar, and the House Rockers became the best electric blues band in the Delta.

The band was primal and they beat their instruments so that the physical sound became as important as the pitch of the notes. People said things about Wolf’s voice like “stronger than forty acres of crushed garlic” (Ronnie Hawkins) or “a runaway bucket of nails” (Newsweek).

KFFA in Helena, Arkansas, began broadcasting King Biscuit Time on 21 November 1941, which makes it the longest running daily radio show in the country.

Emulating KFFA, KWEM gave Wolf a twenty minute slot and he ran with it. “This here’s the Wolf comin’ at you, baby,” he would growl. Another Wolfman would make a whole career out of imitating this comeon.

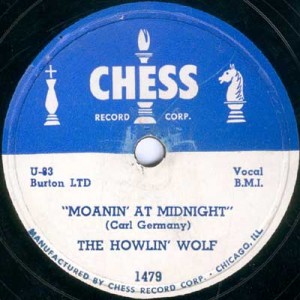

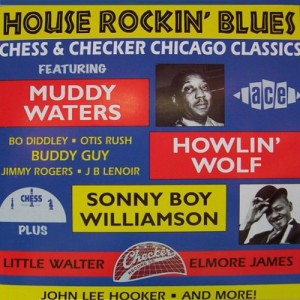

The first song Howlin’ Wolf recorded for Sam Phillips was Moanin’ at Midnight, a magical mantra that began with Wolf howling a B-Bb and then guitarist Willie Johnson begins playing a pattern in E and Wolf starts singing an F#. The whole effect is eerie and elemental. When Big Brother and the Holding Company lived in Lagunitas, California, we tried for three days to learn this song. I always thought we couldn’t because we were young and inexperienced, but I tried the song again a couple of years ago and it still eluded me. It seems as if everyone in the band is playing backwards to each other, and as soon as they settle into one groove, they switch it up and accent another beat. Such a great song.

How Many More Years, probably with Ike Turner on piano, was from the same session. The song is a twelve bar blues in G and the thing that makes it remarkable aside from Wolf’s great voice, emotive delivery and harp playing is the guitar riff that goes G B EDE. A lot of people who copied this song didn’t do that simple figure and they missed a good thing. There are some guitar smears in the middle that illustrate the House Rockers’ pure sound approach to making music. They don’t make “sense,” but they are so cool. It’s rather as if you daubed a vivid color on an already good canvas and all of a sudden it made the painting twice as interesting.

Howlin’ Wolf made the big move to Chicago in 1954 and he did it in style, with his own car and a lot of money. Leonard Chess found him a place to stay… at Muddy Waters’ house.

Wolf recorded No Place To Go at his first Chess session in 1954. This tune hearkens back to the early Delta days when people did songs with no chord changes and the atmosphere was everything, and there was plenty of atmosphere here.

The B side was Rockin’ Daddy, a more conventional dance song. This record entered the charts in May and stayed there till July.

Howlin’ Wolf went back in the studio and recorded a Willie Dixon tune Evil Is Going On,” which stayed on the charts from July until November and sold well not only in Chicago, Memphis and Atlanta, but also in Nashville, Cleveland and Detroit.

Wolf put a Chicago band together with Jody Williams on guitar, Otis Spann and later Hosea Lee Kennard on piano, and the very stylish Hubert Sumlin, another diddley bow player, on guitar. This was a high powered band and Wolf gloried in it. He prowled the stage, he climbed the curtains, he put a coke bottle in his pants, shook it up, opened his zipper and sprayed it on the audience. He lay down on the floor and played the guitar. He played the real thing and he dressed it up in extreme showmanship.

Howlin’ Wolf, despite his background, was a happy man. He was born that way. He communicated his happiness and delight in life to everyone he met. The first thing he said to me was, “You got more soul than I have on my shoe.” Considering that it was a very big shoe (pace Ed Sullivan), I took this as a compliment, because it was the first time I ever heard the expression, and he was laughing and happy, pumping my hand to beat the band as he said it.

He had a microphone cord that must have been fifty yards long and Wolf prowled the environs. He would go out on the street corner and startle passersby, dancing, hollering, moaning. The police often had to take him back to his bandstand. When I played saxophone, I copied this routine from Wolf, of having a very long microphone cord and wandering out into traffic in Oakland blowing my brains out on the horn. It was a lot of fun.

I have to quote something here from Ted Gioa’s already classic study of the Delta Blues. It’s from Robert Palmer who says, “Wolf counted off a bone-crushing rocker, began singing rhythmically, feigned an exit, and suddenly made a flying leap for the curtain at the side of the stage. Holding the microphone under his beefy right arm and singing into it all the while, he began climbing up the curtain, going higher and higher until he was perched far above the stage, the curtain threatening to rip, the audience screaming with delight. Then he loosed his grip, and in a single easy motion, slid right back down the curtain, hit the stage, cut off the tune, and stalked away, to the most ecstatic cheers of the evening.”

We’re talking about a man who is fifty-five years old here. And through it all he was a real musician, everything served the song and the thread was never lost. Wolf had an innate sense of how to make his music better and more understandable, but he always kept it real.

So, Howlin’ Wolf became the most exciting performer in the country. Little Richard and James Brown came to study him and sit in with him. When he played the Apollo Theater, owner Frank Schiffman observed, “I haven’t seen anything like it in my thirty years with the Apollo.”

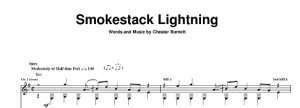

In January 1956 Howlin’ Wolf went into the studio and cut Smokestack Lightning in the key of E, although he had played it in D in the past. The guitar player does a two bar riff that hits the G on the third fret and that’s the tune, no other chord changes. Wolf puts the variety into the song with his mighty crackling voice. Ah-oh, smokestacklightning Shinin’ just like gold Why don’t ya hear me cryin’? Whoo-hoo, whoo-hoo Whoo.

Chester Burnett died on 10 January 1976, after influencing several generations of musicians with his spirited playing and singing and his creative, joyful self.

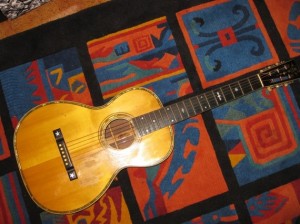

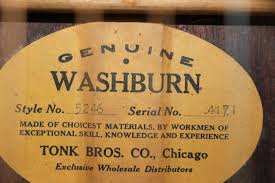

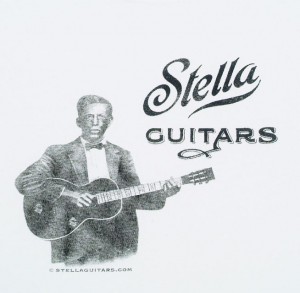

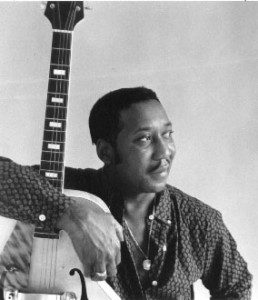

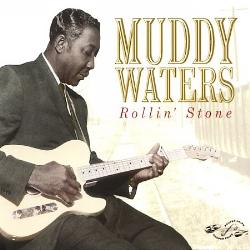

When he was seventeen, Muddy Waters acquired his first guitar for $2.50. It was a Stella, a decent guitar then, but a byword for a cheap, difficult to tune and play guitar by the time I bought my Silvertone, another cheap guitar, in the mid 1950s.

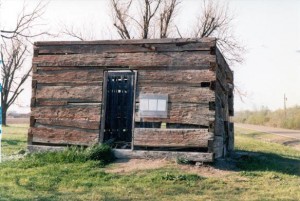

McKinley Morganfield was born on 4 April 1913 in Jug’s Corner in Issaquena County, Mississippi. When he was three, his mother died and he moved to Clarksdale a hundred miles north to live with his grandmother Delia Grant in this cabin on the Stovall Plantation.

In the summer of 1941, Alan Lomax went to Stovall, Mississippi, on behalf of the Library of Congress to record country blues musicians. ”He brought his stuff down and recorded me right in my house, and when he played back the first song I sounded just like anybody’s records. Man, you don’t know how I felt that Saturday afternoon when I heard that voice and it was my own voice. Later on he sent me two copies of the pressing and a check for twenty bucks, and I carried that record up to the corner and put it on the jukebox. Just played it and played it and said, ‘I can do it, I can do it.’” Every musician, every performer will recognize this magic moment.

They called him Muddy Water. McKinley Morganfield was a mouthfull. Later a typo, or an intuitive person, changed the last name to Waters.

He learned his singing from Son House and his guitar playing from Robert Johnson, but Muddy Waters was always an original.

In 1943, Muddy took his mojo to Chicago with the hope of becoming a full-time professional musician. He lived with a relative for a short period while driving a truck and working in a factory by day and performing at night.

Big Bill Broonzy, then one of the leading bluesmen in Chicago, helped Muddy break into a very competitive market by allowing him to open for his shows in the rowdy clubs.

In 1945, Muddy’s uncle, Joe Grant, gave him his first electric guitar, which enabled him to be heard above the noisy crowds.

In 1946, he recorded some tunes for Mayo Williams at Columbia but they were not released at the time.

Later that year he began recording for Aristocrat Records, a newly-formed label run by two brothers, Lejzor and Fiszel Czyz from Motele, Poland. The brothers changed their names to Leonard and Phil Chess. Their father had a business selling empty bottles which a member of Al Capone’s organization bought and filled with bootleg liquor. Leonard Chess then opened a liquor store and later the Mocamba Lounge where the brothers decided to sell records that they made themselves, first at Aristocrat and later at Chess.

In 1947, Muddy played guitar and Sunnyland Smith was on piano playing “Gypsy Woman” and “Little Anna Mae.” These were also shelved, but in 1948, “I Can’t Be Satisfied” and “I Feel Like Going Home” became big hits and Muddy Waters’ popularity in clubs began to take off.

The plantation system still existed, even in Chicago, and, in the beginning, the Chess brothers would not allow Muddy to use his own guitar in the recording studio, because the piano was the respectable instrument in those days.

Muddy was provided with a backing bass by Ernest “Big” Crawford, and by musicians assembled specifically for the recording session, including Leroy Foster and Johnny Jones.

Gradually Chess relented, and by September 1953, Muddy Waters was actually allowed to play his own guitar on recording sessions.

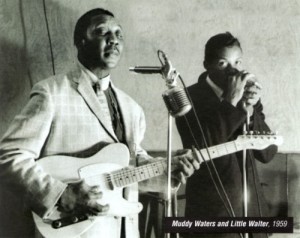

Muddy Waters was now recording with one of the most acclaimed blues groups in history: Little Walter Jacobs on harmonica, Jimmy Rogers on guitar, Elga Edmonds (a.k.a. Elgin Evans) on drums and Otis Spann on piano.

Soon after this, Aristocrat changed their label name to Chess Records and Muddy’s signature tune Rollin’ Stone became a hit. Muddy Waters’ songs were autobiographical and filled with mystical events: a gypsy woman is foretelling his uniqueness, seven doctors preside at the birth of this prophet born on the seventh hour of the seventh day of the seventh month. In the song Mannish Boy recorded in 1955 we are told that Muddy will be the greatest man alive and in I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man, the gypsy says that he will be a son of a gun. No other singer in any style dared to sing songs like this.

Willie Dixon, bass, who was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1915 wrote a lot of songs, I’m Your Hoochee Coochee Man, I Just Want To Make Love To You, I’m Ready, Little Red Rooster, Diddy Wah Diddy, Wang Dang Doodle, My Babe and Mellow Down Easy among many, many others.

Along with his former harmonica player Little Walter Jacobs and recent southern transplant Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy reigned over the early 1950s Chicago blues scene, his band becoming a proving ground for some of the city’s best blues talent. While Little Walter continued a collaborative relationship long after he left Muddy’s band in 1952, appearing on most of Muddy’s classic recordings throughout the 1950s, Muddy developed a long-running, generally good-natured rivalry with Wolf.

Otis Spann from Muddy’s band went on to have a solo career and many releases under his own name beginning in the mid-1950s. He was an intelligent, versatile player and he could be a bandleader himself

Muddy also did quite a bit of playing with an old friend of ours, Willie Mae Thornton.

Another Muddy Waters protégé was Buddy Guy, a thoroughly admirable character who had a great guitar style.

Buddy Guy is a loose, relaxed guy with nothing to prove. His guitar style is easy and casual while he does the most amazing things. And then there is his stage presence which is maniacal, loopy and inspired. Once I saw him when there was a lamp over his head suspended by a wire. As Buddy played, he reached up and swung the lamp around. He would play a run and then push the lamp around in ever increasing circles, making his own crazy light show and playing some great guitar at the same time.

Buddy Guy has a sweet, humble manner and yet he can be a savage on the guitar. He was born in 1936 in Lettsworth, Louisiana, and so is one of the last guitarists from our period. He was a guitar for hire at Chess Records and then went to Vanguard where he did some great work. In his early days, he listened a lot to people like T-Bone Walker and B.B. King. He even did an album of North Mississippi blues, few chord changes and drones in one tonality, like John Lee Hooker.

Muddy Waters died on 30 April 1983 of carcinoma of the lungs and cardiorespiratory arrest. Some of the people at his funeral, B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Memphis Slim, Willie Dixon, Junior Wells, Johnny Winter and James Cotton went to Buddy Guy’s Checkerboard Lounge to jam and say one last goodbye to Muddy.

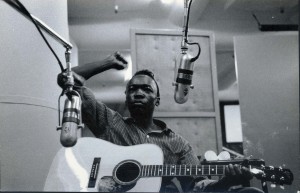

John Lee Hooker is in many ways the closest to me of all these Delta blues people and yet he is more mysterious than any of them both in his music and in the details of his life. There is much that is not known for sure about him, when he was born, how many were in his family and some really basic facts about him.

My friend Rich Kirch played with John Lee for years. Carlos Santana played with him. I’ve talked with him backstage several times. Canned Heat did an album with him. Pete Sears actually wrote and recorded a song with John Lee Hooker, and yet John Lee remains an international man of mystery.

I know his daughter Zakiya and have shared the stage with her several times, notably in Ko Samui, Thailand, where we played at a club called Cocos and also at a festival.

John Lee Hooker was the first of the Delta blues people that I heard, aside from Jimmy Reed, but even today he sounds mysterious to me, mainly because of his music which seems to come from the same mystic place as that of Geeshie Wiley and Skip James, a sacred place, non verbal, rich, religious, deep, ancient.

He was born just outside of Clarksdale, Mississippi, but where? When? Every time you asked him, he gave you a different answer. The courthouse burned down in 1927 so there are no records. None of the other Delta blues people talk about him when he was young. His family say he just left one day. He recorded under a different name almost every time he recorded. His blues sound earlier than the earliest blues.

Don’t look back, indeed. The first thirty years of his life are completely unknown. John Lee says his boogie came from his stepfather Will Moore, a sharecropper born in Shreveport, Louisiana, but nothing else is known about that man. His mother, née Minnie Ramsay, moved in with Will Moore, and John Lee came with her, but the other children stayed with their father, Reverend William Hooker, who allowed John Lee to have a guitar only if he kept it outside the house.

John Lee may have moved away from the Reverend William Hooker, but there is a strong church element in his blues, an instrospective, spiritual quality that he may have learned as a gospel singer in his father’s church.

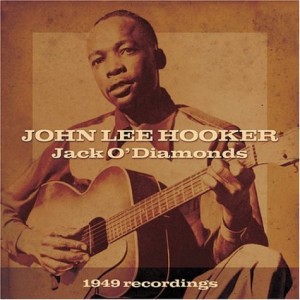

John Lee’s beloved E7 chord. My friend Eugene Skuratowicz, who had much to do with John Lee’s career, gave me a beautiful CD called Jack O’Diamonds that was recorded 1949 in the kitchen of Gene Deitch who did Cat cartoons for Record Changer magazine in the 1940s, 1950s.

After dinner, John Lee performed right there at the dining room table. Deitch, using his studio’s DuKane tape recorder, captured the moment on tape. John Lee sang the songs in his set, and then went on to remember tunes from back then in the Delta, including some from his father’s church. The tape recorder picks up everything, including John Lee’s foot tappings which add much.

John Lee Hooker’s Jack O’Diamonds. I love playing along with it on the guitar. The keys for the first seven tracks are Ab, Db and then at track number eight, Jack O’Diamonds, John Lee gets his guitar in standard tuning and from there on out, the keys become C, D, G.

John Lee Hooker’s recording career began in 1948 when his agent placed a demo, made by Hooker, with the Bihari brothers, owners of the Modern Records label. The company initially released an up-tempo number, Boogie Chillen’,which became Hooker’s first hit single.

Though they were not songwriters, the Biharis often purchased or claimed co-authorship of songs that appeared on their labels, thus securing songwriting royalties for themselves, in addition to their own streams of income. This is not an isolated instance of this disreputable practice. Unscrupulous record company owners and producers signed their names to all kind of songs that they had nothing to do with writing.

The Bihari brothers, Jules, Lester and Saul, used a number of pseudonyms for songwriting credits: Jules was credited as Jules Taub; Joe as Joe Josea; and Sam as Sam Ling. One song by John Lee Hooker, Down Child, is solely credited to Taub, with Hooker receiving no credit at all. Another, Turn Over a New Leaf is credited to Hooker and Ling.

John Lee Hooker recorded over 100 albums. He lived the last years of his life in Long Beach, California. In 1997, he opened a nightclub in San Francisco’s Fillmore District called John Lee Hooker’s Boom Boom Room, after one of his hits.

He fell ill just before a tour of Europe in 2001 and died on June 21 at the age of 83, two months before his 84th birthday.

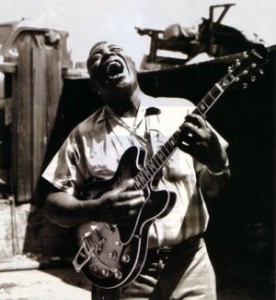

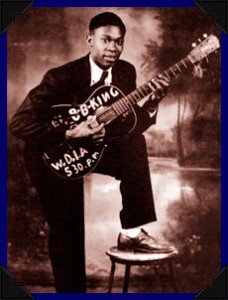

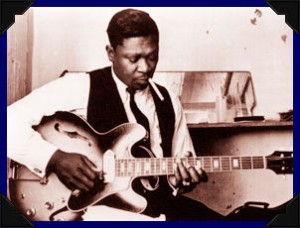

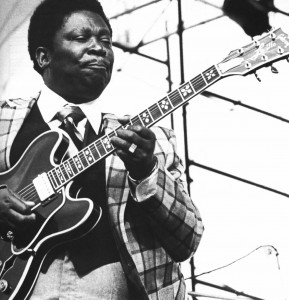

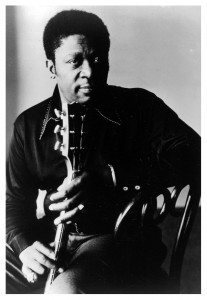

If John Lee Hooker seemed the most remote Delta blues player from contemporary life, B. B. King seemed the closest, and once again it’s right there in the music. Riley B. King played a fluid single note style of guitar that influenced everyone and he learned it, not by following the Delta blues musicians, but by listening to records, just as we all learned from him by listening to his hits. “I believe I listened harder than anyone in the history of listening.”

B.B. King once had 30,000 records and he was a disc jockey. He acquired his first guitar when he was twelve; it was a cherry red Stella that he bought secondhand for fifteen dollars. King’s mother and Booker White’s mother were cousins, so the boy heard White when he visited twice a year, and he learned some music and philosophy from Reverend Archie Fair who taught him a few chords and explained that music could be something more than a sexual, physical thing, that it could express a higher power. It seems that every musician in the Delta struggled at some point between playing for the church and playing for the dancers.

He joined a group called The Famous St. John Gospel Singers, which was influenced by the Golden Gate Quartet and the Dixie Hummingbirds. but B., as his friends call him, found that he made the most money on the street corners when he played the blues.

One day King looked into a ten-cent vending machine that played a film clip of the most famous band at that time, Benny Goodman’s, and there in the middle of all that swing was a black guitar player, Charlie Christian, who was playing single note lines and beautiful harmonies. This was a significant moment in B.B. King’s perception of himself and his work.

King has developed one of the world’s most identifiable guitar styles. He borrowed from Blind Lemon Jefferson, T-Bone Walker and others, integrating his precise and complex vocal-like string bends and his left hand vibrato. The result of listening to those 30,000 records has been that B.B. King has mixed blues, jazz, swing, mainstream pop and jump into a unique sound. He says, “When I sing, I play in my mind; the minute I stop singing orally, I start to sing by playing Lucille.”

King was born (16 September 1925) in a small cabin on a cotton plantation outside of Berclair, Mississippi, to Albert King and Nora Ella Farr on September 16, 1925. In 1930, when King was four years old, his father abandoned the family, and his mother married another man. Because Nora Ella was too poor to raise her son, King was raised by his maternal grandmother Elnora Farr in Kilmichael, Mississippi. He sang in the gospel choir at Elkhorn Baptist Church.

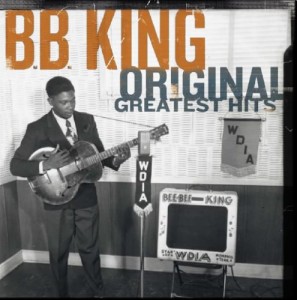

In 1948 B.B. King performed on Sonny Boy Williamson’s radio program on KWEM in West Memphis, where he began to develop a local audience for his sound. King’s appearances led to steady engagements at the Sixteenth Avenue Grill in West Memphis and later to a ten-minute spot on the legendary Memphis radio station WDIA. King’s Spot became so popular, it was expanded and became the Sepia Swing Club.

He worked at WDIA as a singer and disc jockey, gaining the nickname Beale Street Blues Boy, which was later shortened to Blues Boy and finally to B.B. It was there that he first met T-Bone Walker. ”Once I’d heard him for the first time, I knew I’d have to have an electric guitar myself. ‘Had’ to have one, short of stealing!”, he said.

In 1949, King began recording under contract with Los Angeles-based RPM Records. Many of his early recordings were produced by Sam Phillips who later founded Sun Records. ”My very first recordings [in 1949] were for a company out of Nashville called Bullet, the Bullet Record Transcription company,” King recalls. “I had horns that very first session. I had Phineas Newborn on piano; his father played drums, and his brother, Calvin, played guitar with me. I had Tuff Green on bass, Ben Branch, on tenor sax, his brother, Thomas Branch, on trumpet, and a lady trombone player. The Newborn family were the house band at the famous Plantation Inn in West Memphis.”

In the 1950s, B.B. King became one of the most important players in rhythm and blues music, with an impressive list of hits including 3 O’clock Blues, You Know Love You, Woke Up This Morning, Please Love Me, When My Heart Beats like a Hammer, Whole Lotta Love, You Upset Me Baby, Every Day I Have The Blues, Sneakin’ Around, Ten Long Years, Bad Luck, Sweet Little Angel, On My Word of Honor, and Please Accept My Love.

B.B. King made 342 appearances and 3 recording sessions in 1956 alone. In 1962, King signed to ABC-Paramount Records which was later absorbed into MCA Records and thence into his current label, Geffen Records. In November 1964, King recorded the Live At The Regal album at the Regal Theatre in Chicago, Illinois.

Big Brother and the Holding Company played on the same bill with B.B. King several times.

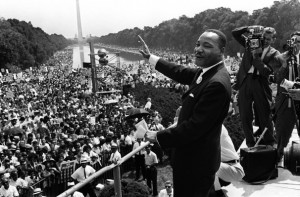

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on 4 April 1968 and we all gathered at Jimi Hendrix’ Generation Club in New York on 7 April to hold a wake for Reverend King. Marci Hooper was there. Noel Redding or Mitch Mitchell was filming with a Super 8 camera. Buddy Guy and Paul Butterfield were there. So was Joni Mitchell. We did Down On Me, Catch Me Daddy, Piece of My Heart and some other tunes. Jimi was at the soundboard. There is a film of this on YouTube somewhere.

B.B. King sat backstage and talked about the tragedy in beautiful, moving terms and then went out to play his set. B’s music was always full of feeling but this night it was something else, sanctified and holy. The music really was serving a higher power that night. This was the most inspiring gig we ever played… by far. B.B. King was the perfect person to lead us through this time.

I’ve left out a lot of the great Delta blues musicians here. People like Mississippi John Hurt, Furry Lewis, Kid Bailey, Arthur Crudup, all great players and true blues people. The sound of the Mississippi Delta in the 1920s, 1930s is still with us today.

__________________________________________________

Sam Andrew

(San Antonio, Texas, 1955, When and where I first heard the music of T-Bone Walker and Charlie Christian.)

_________________________________________________

Superb work and most enjoyable and informative. Cheers