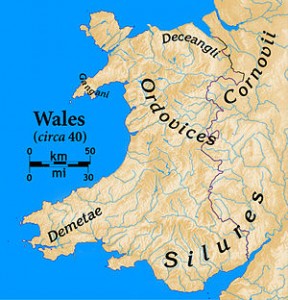

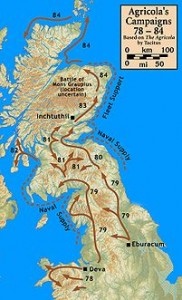

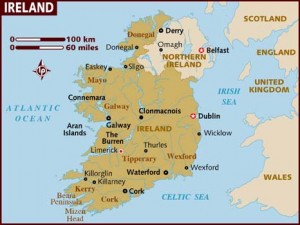

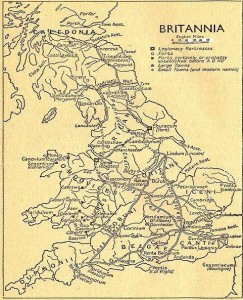

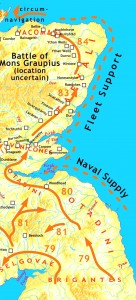

In just seven short years (circa 78-85 CE), Gnaeus Iulius Agricola advanced the military occupation of Britain from his initial campaigns against the Ordovices in North Wales, through the territories of the powerful Brigantes of northern England, and the tribes of lowland Scotland and the eastern Highlands, possibly as far north as Inverness on the Moray Firth. Agricola more than doubled the area of the Roman province of Brittania which, up until then, had taken his ten predecessors a period of thirty-five years to conquer and control.

GNAEUS IULIUS AGRICOLA DUX (the DUX was the leader, the general, the commander in a campaign. The word survives in “duke,” “il Duce,” and “Doge,” the leader in Venice)

Under the DUX was the LEGIO (legion) a group of about five thousand men. A DUX could command several legions, with a legate actually in charge of each legion. The words “legion” and “legate” come from LEGERE, to choose, to levy.

The usual legion commander was the LEGATUS LEGIONIS, the legate.

A COHORS (cohort) was about five hundred men. A legion had ten cohorts.

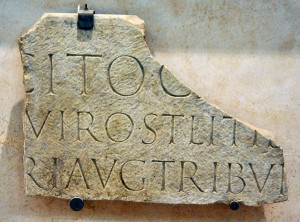

A VEXILLATIO (vexillation) was a group of soldiers under one standard or flag (the study of flags is called vexillology). This plaque was found in Hadrian’s Wall and it says, “Vexillatio Legionis II Augustus et XX Valeria Victrix Fecerunt. (Vexillations from Legion II Augustus and Legion XX Valeria Victrix made this.)

VEXILLATIO LEG XX V V FECIT [The vexillation of Legion 20 Valeria Victrix made (this).] Referring to a part of a wall or building.

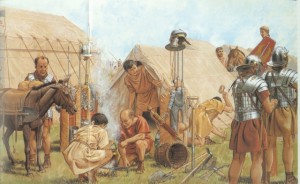

The CONTUBERNIUM (tent group) was eight men who shared a tent.

TRIBUNI (military tribunes) were interns, aristrocratic young men who needed a little military time before beginning their civil careers. Agricola began as a tribune. Tribunes were like young second lieutenants gathered around a senior officer.

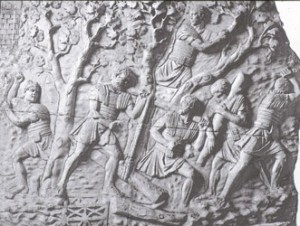

CENTURIONES (centurions) were the sergeants/captains, the backbone of the Roman army. A centurion commanded about eighty men. Notice how his head ornament is lateral instead of axial, as all other helmet decorations were. This was a distinguishing characteristic, easily seen in battle.

PRAEFECTI (prefects) were third in command of a legion, although a prefect could command an entire legion at times. Later we will meet a praefectus (prefect) who commanded a wing of the cavalry.

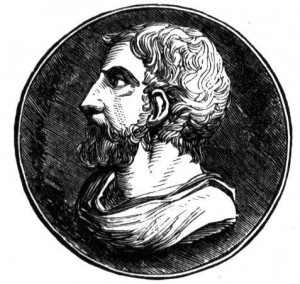

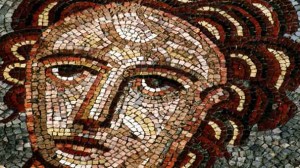

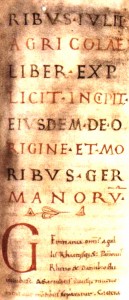

I am reading a book that Cornelius Tacitus wrote about his father in law, Gnaeus Julius Agricola. Tacitus was born in 55 CE, probably in southern Gaul, which the Romans called Provincia and the French today call Provence. Tacitus’ father was a wealthy man who belonged to the second tier of the Roman élite, the Equestres (knights).

Tacitus was sent to Rome to study rhetoric, which at that time meant of course public speaking, but “rhetoric” also connoted a general cultural education that included everything that a magistrate needed to know.

“… this book,” writes Tacitus, ”intended to do honor to Agricola, my father-in-law, will, as an expression of filial regard, be commended, or at least excused.” (“Agricola” means “farmer.” Iulius Agricola in English would be Julius Farmer.)

Agricola served his military apprenticeship in Britain to the satisfaction of Suetonius Paulinus, who was governor from 58–61CE, a painstaking and judicious officer, who, to test Agricola’s merits, selected him to join his staff as one of his military tribunes.

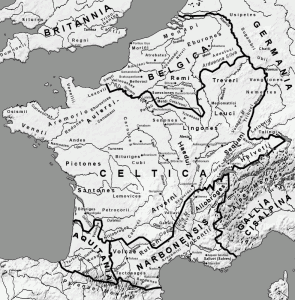

Gnaeus Julius Agricola was born on 13 July 40 CE in Fréjus, France (Forum Iulii, Gallia Narbonensis), then Roman Provincia.

“Fréjus” is actually a corruption of “Forum Iulii.”

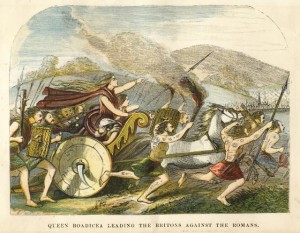

In the year 60, when King Prasutagus of the Iceni died. Governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus was campaigning on the island of Mona (Anglesey, Wales), a stronghold of British resistance to Rome.

The Icenian king Prasutagus, celebrated for his long prosperity, had named the emperor his heir, together with his two daughters; an act of deference which he thought would place his kingdom and household beyond the risk of injury. The result was contrary – so much so that his kingdom was pillaged by centurions, his household by slaves, as though they had been prizes of war.

This was an intolerable situation and Prasutagus rebelled against Roman rule.

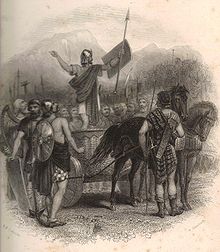

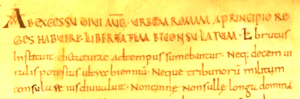

His atque talibus in vicem instincti, Boudicca generis regii femina duce (neque enim sexum in imperiis discernunt) sumpsere universi bellum, ac sparsos per castella milites consectati, expugnatis praesidiis ipsam coloniam invasere ut sedem servitutis, nec ullum in barbaris ingeniis saevitiae genus omisit ira et victoria. (Tacitus, beginning of chapter 16, Agricola)

Urged on by such matters, under the command of the royal Boudica (and sex didn’t matter in choosing leaders), there was universal war, hunting down of Romans in outposts, storming the forts, and even an attack on the whole colony itself, with no omitting of the savagery characteristic of barbarians.

When the Romans executed her husband, Boudica assumed command of the Iceni. She proved a strong and sagacious leader.

Boudica led a revolt which lasted for several months in 60-61 CE. The Boudican forces burned and destoyed three major towns: Londinium (London), Verulamium (St. Albans), and Camulodunum (Colchester).

“Femina duce” Women were held in high respect by the Celts, but the Romans came, whipped Boudica, and raped her daughters.

“colonia” refers to Camulodunum (Colchester) where the Roman veterans had been harrassing the native population.

“Camulodunum” always sounded a lot like “Camelot” to me.

Colchester/Camulodunum is reputed to be the oldest town in Britain and could be seen as the capital city before the Romans came.

“in barbaris ingeniis”: an attributive phrase, meaning (the savagery) “with which barbarians are familiar.”

“ira et victoria” : Fury and the consciousness of victory.

“It is not as a noble, but as one of the people that I am avenging lost freedom,” cried Boudica. Tacitus

The massacre of the Ninth Legion refers to Boudica’s defeat of a large vexillation (soldiers under one flag) of the Legio IX Hispana during the revolt against Roman rule in Britain launched by this queen of the Iceni of Norfolk. Attempting to relieve the besieged colonia of Camulodunum (Colchester, Essex), legionaries of the Legio IX Hispana led by Quintus Petillius Cerealis, were attacked by a horde of British tribes, led by the Iceni. Approximately eighty percent of the Roman soldiers were killed in this battle.

After the final suppression of the revolt of the Iceni, and his apprenticeship with Suetonius Paulinus, Agricola left Britain and was made governor of the province of Aquitania in Gallia (Gaul).

Agricola was consul, and Tacitus but a youth, when Agricola betrothed to the historian his daughter, “a maiden even then of noble promise.” After Agricola’s consulate he gave her to Tacitus in marriage. This estimable and beloved woman is not named in any source, which is typical of the Romans who named their women from clans. Julia was from the clan of the Iulii, Claudia from that of the Claudii, and so on.

Agricola returned to Britain after the Roman civil war of 69 CE among Vitellius, Otho and Vespasian. Agricola was appointed legatus, commander, of the 20th Legion (Legio XX Valeria Victrix). The boar was the symbol of Quirinus, who was seen as the personification of the deified Romulus.

Later Agricola also assumed command of Legio IX in the east of Britain, quartered in Eburacum (York).

Legio XX was stationed for much of its 300 year existence in the west at Chester.

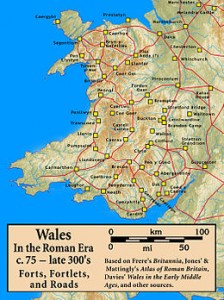

Agricola arrived in Britain, and surprised his soldiers and the Britons as well by fighting the Ordovices when summer, the fighting season, was almost over.

News of Boudica’s Rebellion in 60 forced Suetonius Paulinus to abandon his conquest of Mona (Anglesey). Presumably Agricola had participated in that action, and was now, twenty years later, intent on finishing the job. His decision to attack Mona was swiftly made. There was no naval support because Agricola’s men were excellent swimmers and they also knew the shallows and waded over to Mona. The enemy, who had been looking for a fleet, were completely surprised.

Thus, in his first, short, campaigning season in Britain, Agricola had, in effect, conquered Wales.

“A liking sprang up for our style of dress, and the toga became fashionable. Step by step they (the Britons) were led to things which dispose to vice, the lounge, the bath, the elegant banquet. All this in their ignorance they called civilisation, when it was but a part of their servitude.” (Tacitus, always conscious of the double edged sword that was Roman culture.)

In his second summer (79 CE), Agricola advanced his Legio XX up from Gloucester by the western route, and the Ninth legion from York (Eburacum) in the east.

He conquered the Brigantes in Northern England.

Cartimandua was Queen of the Brigantia, the largest of the Celtic tribes in Britannia. (The name “Bridget” comes from these people.)

Cartimandua’s kingdom was a vast tribal federation located in the neck of Britannia and its seat was at the massive fortification of Stanwick. (Stanwick is the red dot near Wellingborough.)

Cartimandua reigned between 43 – 70 CE. She made peace with the conquering Romans and was allowed to rule as a client-queen.

Because of her friendship with the Romans, Cartimandua refused to join the rebellion of Queen Boudica in 61 CE.

Later, bound by her client-queen relationship with Agricola, she refused aid to Caractacus, king of the Catuvellaunii, and instead surrendered him to the Romans.

Although she was married to Venutius, Cartimandua was a Celtic queen and wielded power in her own right.

A struggle for power broke out between Cartimandua and Venutius and became a civil war among the Brigantes.

Cartimandua asked for and received aid from the Romans to restore peace among her people.

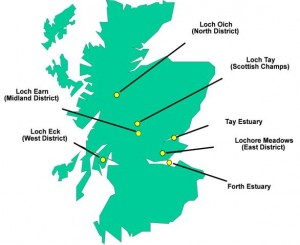

In 79 CE, Agricola marched into Scotland on the eastern side.

The third year of his campaigns (79 CE) opened up new tribes as far perhaps as the Tay estuary.

The enemy did not dare to attack the invaders, harassed though the Romans were by violent storms. There was even time for the erection of forts.

Not a single fort established by Agricola was either stormed by the enemy or abandoned by capitulation or flight. Sorties were continually being made, since these positions were secured from protracted siege by a year’s supply of food and weapons.

Winter brought with it no dangers, and each garrison could hold its own, as the enemy, who had been accustomed often to repair summer losses by winter successes, found himself repelled alike both in summer and winter.

Nec Agricola umquam per alios gesta avidus intercepit: seu centurio seu praefectus incorruptum facti testem habebat.

(Aricola allowed his men to shine. The centurion and the prefect both found in him an impartial witness of their every action.) The prefect here was probably the commander of a wing (ala) of cavalry.

In the fourth summer (80 CE) of his time as Dux Brittaniae, Agricola secured the peoples and land that he had conquered.

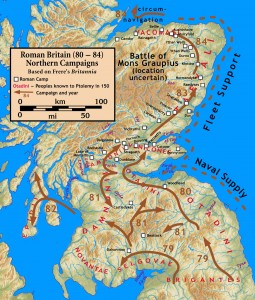

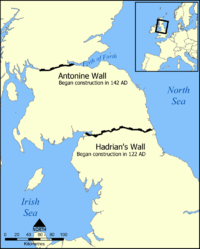

Agricola stopped at this point because the Clota (Clyde) and Bodotria (Forth) nearly cut the land in two (81 CE). Much later, the Romans built Antonine’s Wall which was merely a joining of the garrisons that Agricola had first put here to join the two rivers in cutting the land.

This is as far as the Romans went into Scotland and even today there is a big difference between the people who live between Hadrian’s and Antonine’s walls and the people who live north of Antonine’s wall. They are two Scotlands. The people in the north remained Catholic and Celtic. In the south of Scotland (south of the Antonine Wall) people spoke English and were Protestant.

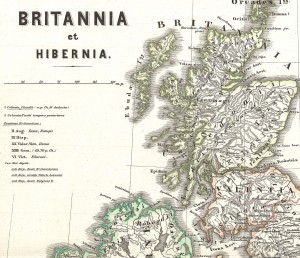

“In that part of Britain which looks toward Ireland, Agricola posted some troops, hoping for fresh conquests rather than fearing attack, inasmuch as Ireland, being between Britain and Spain and conveniently situated for the seas round Gaul, might have been the means of connecting with great mutual benefit the most powerful parts of the empire.” The knowledge of geography, even at this date, was shaky. It was thought at first that Britain might be a peninsula.

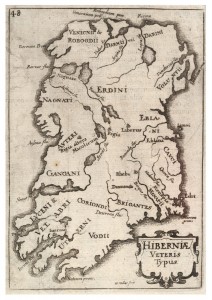

In chapter 24, Tacitus writes that Ireland’s extent is small when compared with Britain, but exceeds the islands of “our” seas (Sardinia, Sicily). Notice that the Brigantes have territory in Ireland also.

“In soil and climate, in the disposition, temper, and habits of its population, Ireland differs but little from Britain.”

“I have often heard Agricola say that a single legion with a few auxiliaries could conquer and occupy Ireland, and that it would have a salutary effect on Britain for the Roman arms to be seen everywhere, and for freedom, so to speak, to be banished from its sight.”

Meanwhile, Agricola was campaigning in the north when the Caledonii took the opportunity to attack the forts to the rear of Agricola’s campaigning column.

Seeking to confront the Caledonii, and without knowing from which glens they would emerge, Agricola split his forces into three separate battlegroups.

The Caledonians, correctly identifying the weakest, most exposed Roman battlegroup gathered their forces together and attacked and almost conquered Legio IX, the Ninth legion. This attack was fought off only with difficulty and reliance on a relief column led by Agricola.

Sometime after 108 CE, Legio IX disappeared from the records. The popular version of events is that the Ninth ~ numbering about 5,000 men ~ was sent to vanquish the Picts in Caledonia and mysteriously never returned. The real reason that the Ninth “disappeared” is probably much more mundane in that they were likely disbanded, but who knows? At any rate, a popular film The Eagle has been made about this question, with the usual Hollywood distortions.

Legio IX was called “Hispana” because Julius Caesar founded it in Spain in 65 BCE.

And now in his work, Tacitus introduces a little diversion because of its inherent interest. On the west coast of Scotland, at Vindogara, probably modern Irvine in Ayrshire, in 82 CE, a cohort of Usipi, that had been recruited in Germania and transferred to Brittania, murdered their centurion and the Roman soldiers who had joined them to teach them discipline.

The Usipi deserted, sailed around the coast of Britain, and escaped to the Continent. This tribe lived in Germania where the Lippe and the Rhine flow together. The Usipi’s voyage in three liburnians around the south of Britain finally demonstrated to Agrigcola that Britain was indeed an island.

The liburnia, so called because the Romans copied the ship design from the pirates of Liburnia, had only two rows of oars, and the Romans came to prefer it because of its great speed and maneuverability.

The Usipi mutineers lost their ships through bad seamanship. The Suebi and the Frisii, taking them for pirates, attacked them and sold them into slavery. So ends this digression in Tacitus’ history.

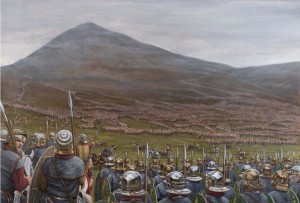

The battle of Mons Graupius was a Roman military victory in 83 CE. The exact location of the battle remains a matter of debate.

Agricola had sent his fleet ahead to panic the Caledonians, and, with light infantry reinforced with British and German auxiliaries, he reached the site, which he found occupied by the enemy.

Even though the Romans were outnumbered in their campaign against the tribes of Britain, they often had difficulties in getting their foes to face them in open battle. The Caledonians were the last to be subdued. After many years of avoiding the fight, the Caledonians were forced to join battle when the Romans marched on the main granaries of the Caledonians, just as they had been filled from the harvest. The Caledonians had no choice but to fight, or starve over the next winter.

Non Romans did much or most of the fighting on the Roman side. The legions were held back, and it was considered a better victory if they didn’t have to enter combat at all. The allied auxiliary infantry (meaning Britons and Germans who sided with Agricola) numbered 8,000 and was in the center of the battle line.

Three thousand cavalry were on the flanks and the legionaries were in front of their camp as a reserve. The Roman army was 17,000 – 30,000 strong, and the Caledonians, stationed on higher ground up the slope of the hill in horseshoe formation, were about 30,000.

After an exchange of missiles, Agricola ordered the auxiliaries to close with the enemy. The Caledonians were cut down and trampled on the lower slopes of the hill. Those at the top attempted an outflanking movement, but were themselves outflanked by Roman cavalry. The Caledonians were then routed and they fled for the shelter of nearby woodland, but were relentlessly pursued by well-organized Roman units.

According to Tacitus, 10,000 Caledonian lives were lost at a cost of only 360 auxiliary troops. This is most likely an exaggeration. Roman accounts of enemy dead were often suspect, especially with such a huge difference in numbers. Twenty thousand Caledonians retreated into the woods, where they fared considerably better against pursuing forces. Roman scouts were unable to locate the remaining Caledonian forces the next morning.

After the battle of Mons Graupius in the north of Scotland, it was proclaimed that Agricola had finally conquered all the tribes of Britain, which is not strictly true, as the Caledonians and their allies remained a threat.

Tacitus’ statement Perdomita Britannia et statim missa (Britain was completely conquered and immediately let go) reflects his bitter disapproval of Emperor Domitian’s failure to unify the whole island under Roman rule after Agricola’s successful campaign.

In the absence of any archaeological evidence and with the very low estimate of Roman casualties, the decisive victory reported by Tacitus may be an invention, either by Tacitus himself, or by Agricola.

Agricola had been governor for an unusually long period and his recall to Rome was overdue, thus he was not recalled on account of his fabricating battle statistics. G. Iulius Agricola was awarded triumphal honors on his return to Rome and was offered another governorship in Syria, so it would seem unlikely that Emperor Domitian was trying to hold him back.

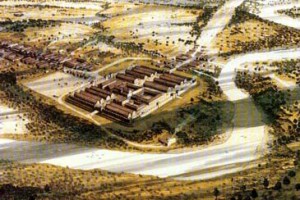

Contrary to Tacitus’ account, archaeological evidence indicates that Domitian did not immediately abandon all efforts to subjugate the remainder of Britain. The construction of a series of forts beyond the Forth,

and in particular the legionary fortress of Inchtuthil were intended to control the territory over which Agricola had advanced.

Over the next few decades, however, the Romans conducted a staged withdrawal towards the eventual frontier demarcated by Hadrian’s Wall.

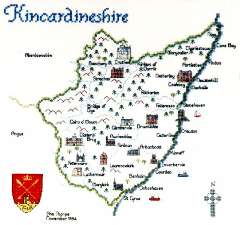

The actual location of the battle of Mons Graupius has caused a lot of healthy debate.

Most of the proposed sites span Perthshire to north of the River Dee, probably near to where Big Brother and the Holding Company played in Glenfarg (2006), about three quarters of the way from Edinburgh to Perth.

A number of authors speculate that the battle occurred in the Grampian Mounth within sight of the North Sea.

In particular, some believe that the high ground of the battle may have been Kempstone Hill, Megray Hill or other knolls near the Raedykes Roman camp.

These sites in Kincardineshire fit the historical descriptions of Tacitus and have also yielded Roman archaelogical finds.

In addition these points of high ground are near the Elsick Mounth, an ancient trackway used by Romans and Caledonians for military maneuvers.

“Agricola was born on the Ides of June in the third consulship of Gaius Caesar; he died in his fifty-fourth year on the tenth day before the Kalends of September in the consulship of Collega and Priscinus.” (13 June 40 to 23 August 93)

“You were fortunate, indeed, Agricola, in your glorious life, but no less so in your timely death. Those who were present at your final words attest that you met your death with a cheerful courage, as though doing your best to absolve the emperor (Domitian) of guilt.”

Thus Tacitus (with a final dig at Domitian) on his father-in-law’s life and death. The entire book Agricola can be seen as a funeral oration to his wife’s father.

Tacitus was a man who wanted to get it right. He was ernest, sincere, very intelligent, and he sought to write his story sine ira et studio, without anger and without zeal (partisanship).

It is through Tacitus’ eyes that we see the first century of the Empire.

When he failed, as he sometimes did, to live up to his promise to preach “the gospel of things as they were,” it was never from a desire to bear false witness.

His view of life was pessimistic and he always knew that the Roman conquest of the world was perhaps not so beneficial for the conquered.

We Americans, of all people, should recognize the desire in the Romans to conquer the world, because of an innate feeling that their/our way of life should be shared among all the nations, that we somehow have found the key to a higher, more organized, “better” life path, that, if only they, the barbarians, would accept it, it would help all peoples to live better lives.

Tacitus was the first person to examine closely this naïve assumption. Sometimes he bought it, sometimes he didn’t, but it makes him an interesting historian to read, two thousand years down the road. I would like to hear what Tacitus would say about such institutions as, for example, the Peace Corps, Starbucks, the Mormon effort and missionaries in general.

Romans were a proselytizing people and so are we, who feel that if we are not converting people to our view of life, that we are somehow failing, or, worse, that our view of life may not be the correct one.

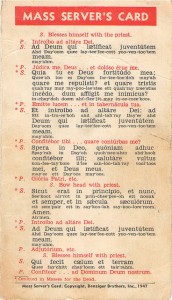

I was raised in the Catholic Church, which is of course, very Roman. The Church inherited the Roman urge toward domination, conquest, triumph, seeking converts, martyrdom, self sacrifice in pursuit of a worthy goal, study, organization, hierarchy, militarism, and a whole (pardon the expression) host of other good and not so good life orientations.

Even though today I am an agnostic, I look at this Church with great interest, just as Tacitus would have, because she is a living, breathing continuation of the Roman Empire.

Tacitus towers above the historians of Rome as Thucydides towered above those of Greece.

Tacitus used the Latin language more creatively and more freely than any author before him. He never indulged in simple minded nostalgia. He knew he had to live his life well in the time that it was given to him, and that there was no going back.

Ab actu ad posse valet illatio. Study of the past will shed light on the future.

Sam Andrew

_________________________________________