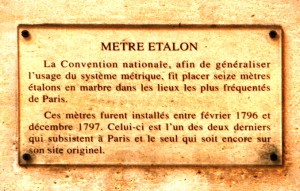

36, rue de Vaugirard Paris

Metre Standard: The national Convention, in order to spread the use of the metric system, put sixteen marble metre standards in the most frequented places in Paris. These metres were installed between February 1796 and December 1797. Here is one of the last two that exist in Paris and it is the only one still in its original place.

The late eighteenth century was a time of revolution.

The preceding century was an age of science. The leisure classes had laboratories in their homes and did all manner of experiments and tests. The result was an air of skepticism and inquiry into all things.

After all of this examination of received notions, the nations of Europe and the Americas were ready for radical changes in their lives. People wanted to put their laws, traditions, religions, customs on a more rational, humane and logical basis.

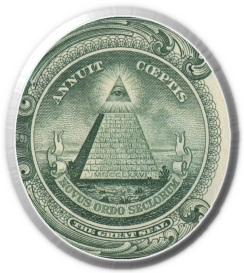

On the back of the dollar bill and on the Great Seal of the United States is written Novus ordo seclorum, a line from the fourth Eclogue of Virgil, which means “a new order of the ages,” and so it was. Things were changing in radical ways, particularly in France, Great Britain and America.

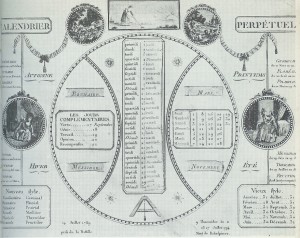

So, in this “new order of the ages,” the first thing to be put on a rational basis was time. The Revolution was a new beginning in human history. The Gregorian Calendar was concerned chiefly with the holy days of saints long dead, and perhaps even non existent. I had this holy card when I was a child. It depicts St. Christopher (which, after all, means no more than “Christ bearer”) carrying a German child across a river, the Rhine? The Danube? Both of these rivers arise near Lake Constance in the Alps and are easily fordable there, even carrying a small, holy looking boy.

One of our recent Popes declared Saint Christopher to be nonexistent, which was very hard on the dashboard/icon sales people. Anyway, the point is that the Gregorian calendar was identified with the nobility and the clergy of the Ancien Régime, and it was time to put the calendar on a real and rational basis, because this is a Revolution and we have to redo everything, including a lot of things that were working just fine.

So, now the savants and philosophes are going to make a calendar that is rational and which will accurately describe what the different parts of the year actually feel like. The new calendar would have twelve months of thirty days each which would be called

vendémiaire month of the wine harvest September/October

brumaire month of fog October/November

frimaire month of frost November/December

nivôse month of snow December/January

pluviôse month of rain January/February

ventôse month of wind February/March

germinal month of germination March/April

floréal month of flowering April/May

prairal month of meadows May/June

messidor month of the harvest June/July

thermidor month of heat July/August

fructidor month of fruits August/September

Each month was divided into three ten-day weeks (décades) with a holiday in the middle of each week called quintidi. There would be a festival (sans-culottide) of five days, six in leap years, to ensure that each year begin anew on the autumnal equinox.

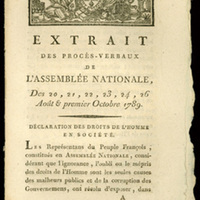

The Revolutionary calendar was born in October 1793 and began with the year II.

This calendar was abolished early in the year XIV in time to start 1806 on January I.

The initial big idea in the French Revolution was that the age of reason had arrived. It was time to look at all the old ideas, the nobility, the church, clergy, the status of women, slavery, the calendar, language, weights, measures, everything, and to make sense of these things, to make them reasonable, simpler, more scientific.

People took the idea of liberty, equality and fraternity seriously. Marie-Olympe de Gouges wrote: ”Why are Black people enslaved? The color of people’s skin only suggests a slight difference. There is no discord between day and night, the sun and the moon and between the stars and dark sky. All is varied; it is the beauty of nature. Why destroy nature’s work?“

There were those in the Assemblée Nationale who believed in rights for blacks and who worked for the abolition of slavery.

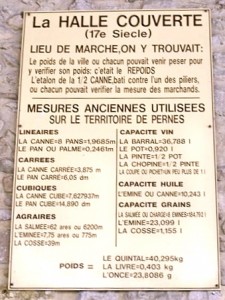

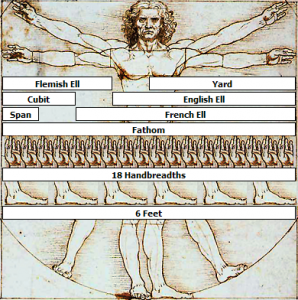

The savants (scientists) in the eighteenth century were also apalled by the lack of uniformity in the weights and measures of their societies. Everything was local and peculiar because it was under the local aristocrat’s control. Measures differed from nation to nation, yes, but also within nations and sometimes even from town to town there were different ideas about what a pint, an ell, a cubit, an inch, a yard was. This diversity made scientific communication very difficult but it was even more disastrous for commerce.

The savants noted that in the Ancien Régime there were eight hundred terms for measurement that covered an amazing 250,000 different units of weights and measures.

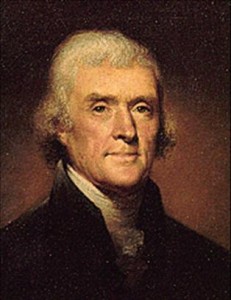

Thomas Jefferson urged Americans to adopt the decimal metric system in weights and measures and in money. We adopted the metric system for money (10 dimes = a dollar, and so on), but we kept the medieval inch, foot, yard, mile, bushel, peck, and all the rest. The result has been havoc ever since.

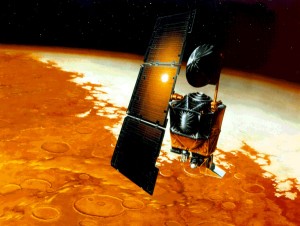

In 1999 a NASA investigation into the failure of the Mars Climate Orbiter showed that one team used “American” units (e.g., inches, feet and pounds) while the other used metric units for a key spacecraft operation. This information was critical to the maneuvers required to place the spacecraft in the proper Mars orbit. The result was a trajectory error of sixty miles. The savants during the French Revolution had created the metric system to avoid just this kind of scientific miscommunication.

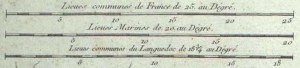

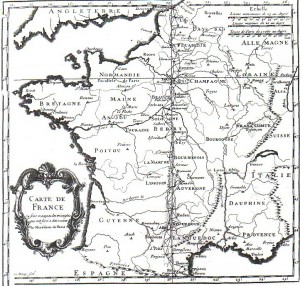

Here are some French measure names from the Ancien Régime: arpent (acre), aune (ell), lieue ancienne (this is an old French league defined as 10,000, a myriad, feet and it was the official French league until 1674.), lieue de Paris (defined in 1674 as exactly 2000 toises. After 1737, it was also called the “league of bridges and roads” (des Ponts et des Chaussées), Lieue de postes (This league is 2200 toises. It was created in 1737.), ligne (line), perche d’arpent (a “rod,” roughly seven metres), pied du roi (foot), point (point), pouce (inch, “thumb”), toise (fathom, used in France, but not in England, as a measure on land as well as at sea, six feet).

The pas (step) had the same value that it had for Julius Caesar who reckoned miles as mille passus, a thousand steps. “Mile” comes from “mille.”

Lieue de 25 au degré (linked to the circumference of the Earth, with 25 lieues (leagues) making up one degree of a great circle. It was measured by Picard in 1669 to be 2282 toises).

Lieue tarifaire. This league is 2400 toises. It was created in 1737.

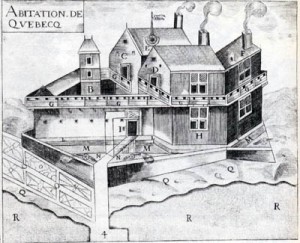

The perche du roi was the rod used in Québec and Louisiana.

The vergée was an area measurement of five perches on each side. This word “vergée” is not only the origin for “verge,” yard, but also for the origin of, “I am on the verge of loving you insanely.”

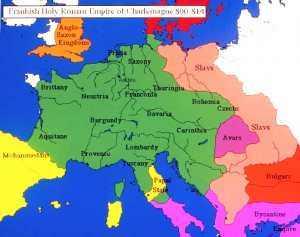

Before the Revolution French units of measurement were based on the Carolingian system, introduced by Charlemagne (800 – 814 CE) which in turn were based on ancient Roman measures.

Charlemagne brought a consistent system to measures across the entire empire. However, after his death the empire fragmented and many rulers introduced their own variants of the units of measure.

Some of Charlemagne’s units of measure, such as the pied du roi (the king’s foot) remained virtually unchanged for about a thousand years, while others, such as the aune (the ell, used to measure cloth) and the livre (pound) varied dramatically from locality to locality. By the time of the revolution, the number of units of measure had grown to the extent that it was almost impossible to keep track of them.

The aune (ell), mainly but not always, a cloth measure, varied often within the same town, and often depended on whether the item measured were wool or silk. Insane, but lucrative for wily merchants.

Flood levels at the pont Wilson at Tours in both metre and pied royal.

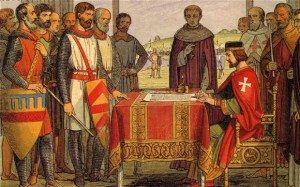

In England the Magna Carta decreed that “there shall be one unit of measure throughout the realm.” Charlemagne and successive kings had tried but failed to impose such a unified system of measurement in France.

Now came the juridical revolution of August 1789, when the French nobility were obliged to renounce all privileges, including the authority over weights and measures. This was the time of la Grande Peur, the great fear, and on the morning of the fifth of August, the Assembly abolished the feudal system eliminating many clerical and noble rights and privileges. The August decrees were finally completed a week later.

The first stipulation put forth by savants, legislators and pamphleteers was the expectation that the new weights and measures would apply equally throughout France.

In March 1790, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, perhaps with more than a little help from his friend, Condorcet, put forth the most thoughtful and cogent proposals for the new standards of measurement.

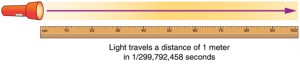

The legislature should derive its fundamental measure from nature, the common heritage of all humanity, which would transcend the interests of any single nation. The various units of the new measurement (length, area, capacity, weight, volume) should be derived from one source and have one system. A grave, as the gram was then called, would be one cubic centimeter of rainwater weighed in a vacuum at the melting point of ice. Everything, then, was to depend on the final answer: how long is the metre on which every other measure was to be based?

All the savants wanted the new measure to be decimal. Simon Stevin, the Flemish engineer, had “invented” the decimal point in the Renaissance. (The Chinese, Arabs and Indians might have a lot to say about this.) John Locke and Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban argued for the virtues of a decimal system.

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier, who was soon to lose his head in the outrageous excesses of the Revolution, strongly advocated that decimal measurement be adopted. At the height of the French Revolution, he was accused by Jean-Paul Marat of selling adulterated tobacco and of other crimes, and was eventually guillotined a year after Marat’s death.

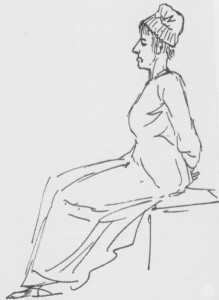

Sketch by Jacques-Louis David of Marie-Antoinette on her way to the guillotine. Stupid, crazy, ridiculous, out of control years. So, right in the middle of all this reason and logic comes one of the most irrational, illogical episodes. One is reminded of the Chinese curse: May you live in interesting times.

The decimal system is natural, because, of course, we have ten digits on our hands, and ten more on our toes.

The only other numbering system which could rival decimal for naturalness would be the Celtic (and Mayan) vigesimal counting system based on 20. The French don’t say eighty, although they have a word for eighty from Lain (octante). They say quatre vingts (four twentys) because they still remember their Celtic ancestors who counted in twentys. To say 75 in French, you don’t say “septante-cinq” which would seem to be logical, you say soixante-quinze, which is sixty ( 3 twentys) fifteen, again because of the Celts.

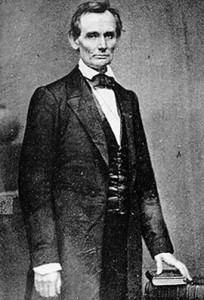

When Abraham Lincoln said “four score and seven years ago,” which was archaic even when he spoke it, he was speaking vigesimally. Not long ago many of us counted in twenties.

The Mayans also had the vigesimal system for counting.

Many other systems were proposed… 12 for divisiblity, 11 because eleven is a prime number and can’t be divided Every number was considered, but the decimal system seemed the most logical because, well, every morning when you look down at your feet, there are ten toes.

The last big debate among the savants was the nomenclature of prefixes, what were these new measures to be called? In May 1790, citoyen Auguste-Savinien Leblond proposed the name “mètre,” “a name so expressive that I would almost say it was French.” One reason for the expressiveness might be that “mètre” sounds a lot like “maître” (master, expert, capable, basic).

The proposal for Greek and Latin prefixes (giga-, mega-, kilo-, hecto-, deca-, milli-, centi-) first appeared in a report by the Commission of Weights and Measures in May 1793.

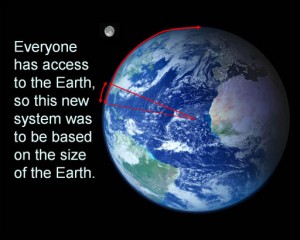

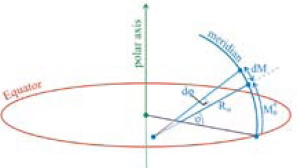

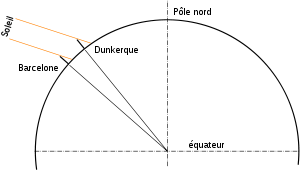

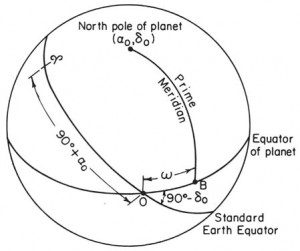

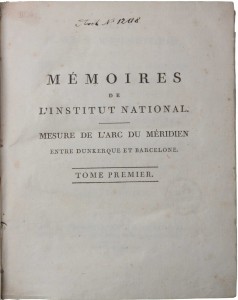

Now the thing to do was find out how long the mètre actually was. What was one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the equator?

The savants knew that a measure of length taken from a quarter of a meridian divided by ten million would be close to the length of the aune of Paris, that is, about three feet, comfortably on a human scale and familiar to everyone. Indeed, this is what makes the meter easy for us Americans today. The meter is close to the yard which is close to one half the length of the human body.

The meter/yard is roughly the distance from your nose to the end of the finger on your outstretched hand.

It wouldn’t be necessary to measure the entire quarter of a meridian to find the length of a meter, but merely an arc, a part of it.

1. The selected arc would have to be as long as at least ten degrees of latitude so that there could be an accurate extrapolation to the whole quarter meridian.

2. The selected arc would have to be over the 45th parallel, halfway between the pole and the equator.

3. The two end points of the “sample,” the selected arc, would have to be located at sea level, and,

4. the meridian sample would have to cross a region already fairly well surveyed so that the measurement could proceed rapidly.

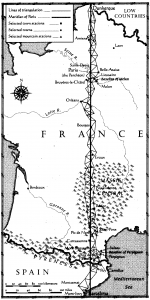

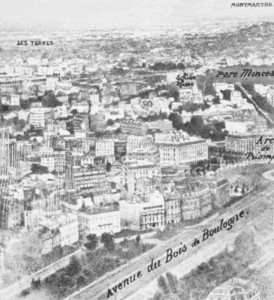

One meridian arc in the entire world met these requirements, the one that ran from Dunkerque (Dunkirk) to Barcelona through Paris.

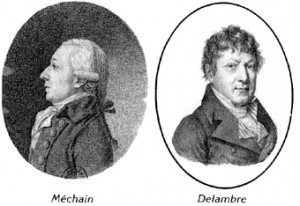

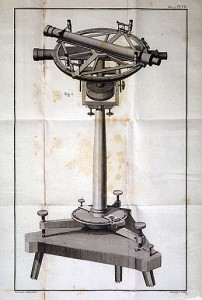

In July of 1792 two astronomers left Paris to find the answer to how long the mètre was. Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Delambre headed north from the capital to Dunkerque.

The cautious, scrupulous Pierre-François-André Méchain traveled to the south, destination Barcelona. The idea was nothing less than the making of a new measure, the meter, which would be one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the equator. This meter was to be the “one unit of measure throughout the realm,” as the Magna Carta had put it. All other measurements would flow from the meter, centimeter, millimeter, kilometer, gram, kilogram, hectare and so on.

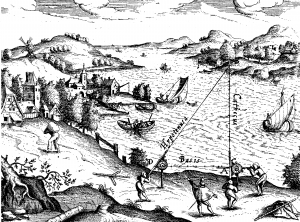

The two men, Delambre and Méchain, wanted to measure that part of the meridian arc which ran from Dunkerque through Paris to Barcelona.

The unit of measure that they thus obtained would be naural, from the earth itself, and would belong to the whole world, since it came from the world.

For seven years Delambre and Méchain measured along the meridian, trying to find out exactly what one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the equator would look like. In the meantime a “provisional metre” was used so that the metric system could be introduced in France and elsewhere. There was a vague idea that the eventual metre would be something like three feet (three pieds du roi).

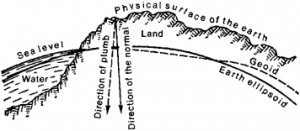

This is geodesy or geodetic surveying, the theory and practice of determining the position of points on the earth’s surface and the dimensions of areas so large that the curvature of the earth must be taken into account. Geodetic surveying is distinguished from plane surveying, the operations of which are executed without regard to the earth’s curvature.

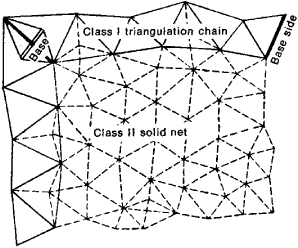

In geodetic surveying, two points, called stations, many miles apart are selected, and the latitude and longitude of each is determined by astronomical means. The line between these two points, the base line, is measured with a high degree of accuracy. The position of a third station is determined by the angle it makes with each end of the base line. This process, called triangulation, is continued until the whole area to be surveyed is mapped.

Where the curvature of the earth is great or where there are hills or high trees between stations, towers are built, or tall structures such as churches are used, so that one station may be seen from another. This geodetic station is on Mallorca.

Ken Alder, an associate professor of history at Northwestern University, has written a book The Measure of All Things about Delambre and Méchain and their trials and tribulations with measuring one ten-millionth of the distance from the north pole to the equator through Paris, and this “through Paris” is an important qualification because, as it turns out, not all meridians are created equal which is the crux of a very big problem.

In his research for this excellent book, Dr. Alder discovered, apparently for the first time, an error that Pierre-François-André Méchain made while doing his survey near Barcelona.

Méchain, despite his cautious, precise and almost overly exact approach to his work, made the error in the early years of the expedition and then covered it up, which was not like him at all. (There were extenuating circumstances. Spain was at war with revolutionary, godless France and Méchain was not allowed to reclimb Mont-Jouy near Barcelona harbor and recheck his work.)

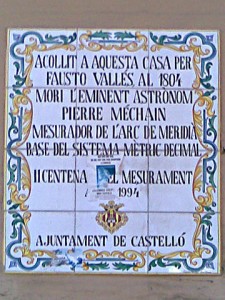

From the Spanish wikipedia: En 1787 Méchain colaboró con J.D. Cassini y Legendre en la medida precisa de la longitud entre Paris y Greenwich Estos tres científicos visitaron en numerosas ocasiones a William Herschel en su observatório astrónico, Slough (Inglaterra) en el mismo año. Fue destinado a España, para precisar las medidas de este meridiano. Durante una breve estancia en Barcelona, notó un pequeño desvío de tres segundos en un arco del meridiano de Dunkerque-Barcelona. A su llegada a Castellón, se incorporó a un gabinete local liderado por Fausto Vallés encargado de fijar el meridiano 0 de la tierra, a partir del cual nacería al metro.

(In 1787 Méchain collaborated with J.D. Cassini and Adrien-Marie Legendre on the precise measurement of the longitude between Paris and Greenwich. These three savants (scientists) visited William Herschel, above, on numerous occasions at his astronomical observatory at Slough (England) in the same year. Méchain was headed for Spain to determine with precision the measurements of this meridian. During a brief stay at Barcelona, he noted a small deviation of three seconds in the arc of the meridian from Dunkerque to Barcelona. Upon his arrival in Castellón, he joined a local cabinet led by Fausto Vallés charged with fixing meridian 0 of the earth, from which was born the meter.)

When my brother Bill and I lived in Paris (1962-1964), one of the places we lived was on rue Legendre, named for Adrien-Marie Legendre, one of these scientists assigned to find the measurement of the longitude between London and Paris.

A year or two ago in a sentimental moment, I visited this street and took a photo of the nameplate which reads merely Adrien-Marie Legendre, mathématicien. This is how rue Legendre looked in great grandmother’s day.

And how it looks now. Bill and I lived there somewhere in between these two images. We lived there with some “putains allemandes” (German whores) as our landlady (évidemment une commère) so kindly called them. (They were simply two young women who visited us and we spoke about German etymology and dialects across France and the motherland.) I really loved Kristin, as one of them was called and I am sorry I have lost contact with her. She was very intelligent and good company.

We never spoke Kristin’s language or ours. All of our conversation was French. Later I visited Germany, and worked there for a while, and upon my return to Paris spoke to Kristin’s parents in German (“Ich bin in der Nähe von Kassel gewesen.” I was near Kassel.), and she said, “Unglaublich! Er hat vorher kein Wort gesprochen.” (Unbelievable, he didn’t know a single word before.) It was the first time either of us had heard the other speak our native language.

Our mutual friend Ulrich Roski, with whom I attended the Sorbonne, and who later became a television and music celebrity in Germany, talked about our relationship in a book he wrote published only in Germany.

Anyway, when I hear the name Legendre, this is what comes to mind. My brother Bill, Ulrich, Kristin and many other close friends. For years after I returned to the United States, Ulrich and I wrote to each other in Latin.

Ulrich was a better scholar than I, by far, and I wish I would have reconnected with him before he died in 2003.

Ulrich Roski with his daughter Sandra.

Pierre-François-André Méchain was of course obsessed with his geodetic surveying error and nearly driven mad by his knowledge that he had betrayed the noble cause of Science by a mistake the thickness of two pieces of paper. He died in an attempt to correct himself. If only he had known that there was no correction possible.

So, the meter, which was thought to be from and of the earth, is an error, an error that has been repeated with its every new redefinition,

including our modern view of the meter in terms of distance traveled by light in a fraction of a second.

But, so what? For one thing, the error is small, very small. For another, how can you really measure a quarter of a meridian anyway? And then derive one ten-millionth of it? And then who cares? Isn’t it enough that we have a convenient, user friendly measure that everyone agrees on? Isn’t that the main thing? So what if the meter is the mismeasure of almost everything.

I suspect that none of these considerations would matter at all to Pierre-François-André Méchain. He was a very emotional man, inclined to self doubt and agonies of indecision, and completely devoted to being precise.

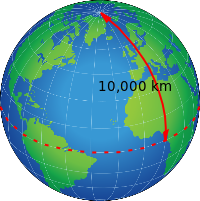

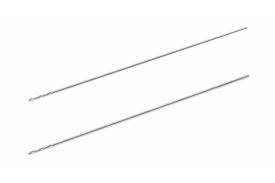

How small is the error? Today’s satellite surveys show that the length of the meridian from the North Pole to the equator is 10,002,290 meters. This means that the meter calculated by Delambre and Méchain is about 0.2 millimeters short, roughly the thickness of two sheets of paper. These are two drill bits, each 0.2 millimeters thick.

And who says the satellite surveys are correct, for that matter? These are today’s measurements? What will tomorrow’s say? Precision is a non ending quest. Perfect for people with obsessive compulsive disorders.

By the way, in writing this I kept spelling Méchain “méchant,” which is French for “malicious, wicked, naughty.”

Do you suppose that this qualifies as a Freudian slip?

It’s not as if Méchain were the big, bad wolf

or anything like that.

To be a little more, pardon the expression, precise, Pierre-François-André Méchain maybe should have been a little more like a wolf. Instead he was so lamblike, real, exposed, passionate, giving that he could not forgive himself for an error that would not have bothered a man like, just to take one example, Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Delambre, who was much more, to use our idiom, “well adjusted,” and who was conducting his triangulations one after the other in the north, peacefully and productively, nearing his goal and waiting for Méchain to finish his work so that they could take their joint calculations to the Académie.

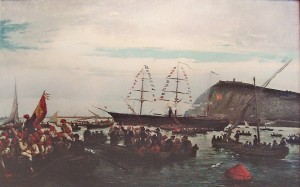

It seemed for a while as if Méchain had given up on his southern measurements entirely. He sailed to Livorno, which for some inexplicable reason, is known as “Leghorn” in English, and there in Genova (Genoa) made friends with Giuseppe Slop de Cadenburg, the director of the astronomical observatory in the nearby university town of Pisa, ten miles north in Toscano (Tuscany), who proved a sympathetic listener to Méchain’s tale of woe.

Perhaps a quote from Méchain will make clear his state of mind: ”Even I, who can claim some experience and competence in geodesy, who know a bit about what methods to use and when to take precautions, even I work in constant fear: I mistrust myself. I continually solicit the views and intelligence of my colleagues at the Academy and the Bureau of Longitudes, and nothing pains me more than when they respond that they rely entirely on me, and that no one is better placed than I to judge what must be done, to choose the right methods, and to carry them through. At such times I feel as if they are spitting in my face. Nothing comes easily, nothing is simple, when one seeks precision. All it takes to be convinced of this is to do a little observing of one’s own.”

On 20 September 1804, Pierre-François-André Méchain died of malaria, probably contracted while he was triangulating in the Albufera marshes near Valencia.

This man was his own worst enemy, tortured, honest, intellectual, precise to a fault, and that cliché never fit anyone more aptly.

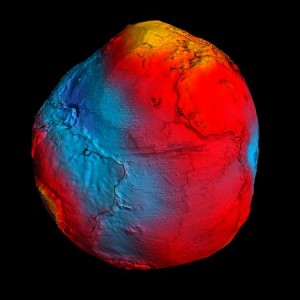

Not all meridians are equal. The earth, as you may have suspected, is lumpy, not perfectly spherical at all, misshapen, a work in progress. Far from being a perfect sphere, the earth is not even an oblate spheroid. It is a piece of mud and rock, different in all places, an organic being, unfinished, very difficult to measure, and not at all the same in different places.

The meridian at Rome is not the same length as the meridian that runs through Paris. We know that now. They didn’t know that then and they assumed that all meridians were equal since the earth was a perfect sphere. They searched for perfect uniformity then, but now we know that perfect uniformity is an expensive illusion, as are so many other illusions.

Méchain did not know that the earth was not a perfect sphere. Neither did Delambre nor anyone else in the world at that time.

The very planet we live on is pimply and imperfect. Pierre-François-André Méchain did not know that. He was an atheist, a scientist, but he still had the faith that we live on a perfect planet with a uniformly perfect shape and that faith was his undoing. He never could understand why his measurements went wrong. They were wrong because the earth is “wrong.”

It wasn’t Méchain’s fault that his measurements were off. What was his fault was that he tried to cover up his “error.” He wasn’t honest about his findings.

Honesty in science is a sine qua non. Sine qua non = ”without which nothing.” Science, knowledge, cannot exist without honesty.

Méchain came from a humble family, but by dint of hard work and study, patient observation and fastidious calculation he had risen to the utmost pinnacle of astronomy in France. Méchain had discovered eleven comets mainly through a kind of obsinacy about being accurate.

Méchain was something of a martyr to the endless and fruitless quest for perfection, not out of a search for personal glory, but for the real aim of devotion to science, to the pure pursuit of knowledge. He was the real thing, the real scientist. It’s just that he was so emotional and tormented by self doubt that he carried his own self destruction around with him. It’s not an unfamiliar pattern, is it?

Méchain’s partner, Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Delambre, noted that Méchain sometimes seemed to be late on his mission, melancholy and a martyr to the endless quest for precision.

Delambre also said, “From this day forth, my most cherished occupation will be to extract from this archive everything that may contribute to the glory of a colleague with whom I was honorably bound in a long common labor. And if I have not succeeded today in painting a picture of the departed astronomer worthy of his merits and the feelings I have for him, I am at least certain that whatever I publish of his work will do far more for his memory than even the most eloquent oration.”

Thank you for reading.

See you next week.

___________________________________________