Ants

The word ant is derived from ante of Middle English which in turn is derived from æmette of Old English and is related to the Old High German ?meiza, hence the modern German Ameise.

Many of the shots below, particularly the better ones were taken by Dr. Alex Wild, whose work may be found at www.alexanderwild.com

Dr. Wild is a biologist at the University of Illinois where he studies the evolutionary history of various groups of insects. Alex conducts photography as an aesthetic complement to his scientific work. We highly recommend a visit to his site and note that all of his photographs are copyrighted.

All of these words come from West Germanic *amaitjo, and the original meaning of the word was “the biter” (from Proto-Germanic *ai-, “off, away” + *mait- “cut”).

The family name Formicidae is derived from the Latin form?ca (“ant”) from which the words in other Romance languages such as the Portuguese formiga, Italian formica, Spanish hormiga, Romanian furnic? and French fourmi are derived.

It has been hypothesized that a Proto Indo European word *morwi- was used (Sanskrit vamrah, Latin form?ca, Greek ?????? mýrm?x, Old Church Slavonic mraviji, Old Irish moirb, Old Norse maurr).

From the Greek ?????? mýrm?x, we get the scientific name for the study of ants, myrmecology. This is the Croatian version of the word.

For every human in the world there are one million ants and a human weighs a million times more than an ant, so that works out to the same presence on earth for humans and ants. Taken altogether, they weigh as much as we do taken altogether.

The ant’s sense of smell is as acute as the dog’s. Ants have survived on earth for more than 100 million years. Not many other animals can make that statement. There are more than 12,000 species of ants all over the world. An ant can lift twenty times her own body weight.

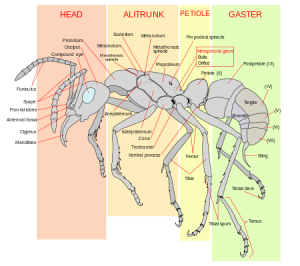

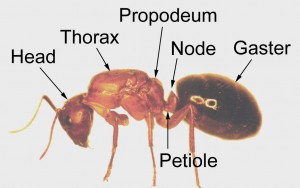

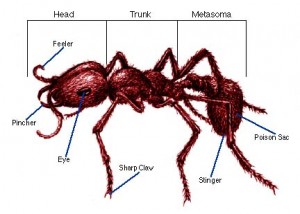

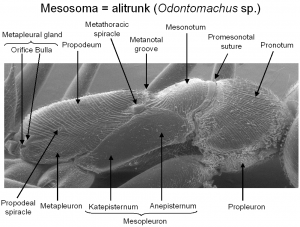

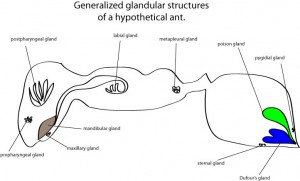

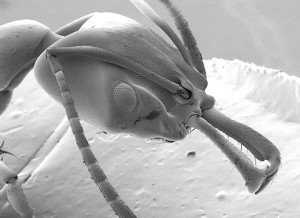

Ants have elbowed antennae, metapleural glands, and a constriction of their second abdominal segment into a node-like petiole. The head, mesosoma and metasoma are the three distinct body segments. The petiole forms a narrow waist between their mesosoma and gaster (metasoma).

Ants have an exoskeleton, an external covering that provides a protective casing around the body and a point of attachment for muscles, in contrast to the internal skeletons of humans.

Insects do not have lungs. Oxygen and other gases such as carbon dioxide pass through their exoskeleton via tiny valves called spiracles.

Insects also lack closed blood vessels; instead, they have a long, thin, perforated tube along the top of the body ( the “dorsal aorta”) that functions like a heart, and pumps hemolymph toward the head, thus driving the circulation of the internal fluids. The nervous system consists of a ventral nerve cords that runs the length of the body, with several ganglia and branches along the way.

An ant worker is less than one millionth the size of a human being, but if you weighed all of the ants in the world they would be about the same poundage as all of the human beings in the world. Ants feast on insects and spiders and they clean up ninety percent of their dead bodies dragging them back to their nests for food. Ants spread seeds around the world and they move more soil than earthworms. They live deep in the ground and high up in the trees. Whilst this is true, some homeowners may have seen some ants in their backyards. Ants can become a nuisance when there seems to be an infestation of them. They don’t cause a lot of damage, but they can distrupt the soil around plants. This can have an impact on the growth of the plant. If these ants seem to be causing some problems, homeowners could always visit https://www.lawncare.net/service-areas/michigan/ to see if they could remove this problem. Hopefully, that will keep plants safe. Ants, termites, stingless bees and polybiine wasps make up an astonishing eighty percent of the insect biomass. (Photo: Alex Wild www.alexanderwild.com)

Ants are as social as humans, which probably accounts for their success as a species. An ant colony is a superorganism, a social unit. As long as the queen lives, the gene pool is secure. The individual worker, warrior, caregiver is nonreproductive and completely expendable. The colony is immortal, churning out queens and males year after year. Solitary insects are pioneers. They can go to strange places and live for a long time. Ant colonies take time to grow and they move slowly but once they get going it is difficult to halt their progress.

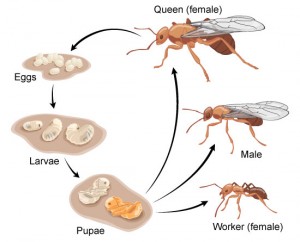

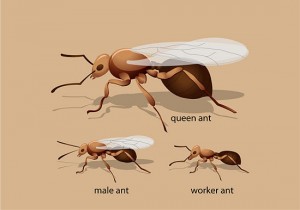

An ant begins as an egg, which if fertilized will be female (diploid). If the egg isn’t fertilized, it will be male (haploid). There is a complete metamorphosis, larval and pupal stages before adulthood. The larva is largely immobile and is fed and cared for by workers. Food is given to the larvae by trophallaxis. The feeding ant regurgitates liquid food from her crop, the “social stomach.” Adults also share food this way. Larvae may also be fed solid food such as pieces of insects brought back to the nest.

The larvae molt several times and then begin the pupal development. Their appendages are free, unlike butterflies at the same stage. Whether the larva becomes a queen, a worker, and what caste she belongs to is determined in some species by what kind of food she is given. Larvae and pupae need to be kept at fairly constant temperatures to ensure proper development, and so often, are moved around among the various brood chambers within the colony.

A new worker spends her first few days of adult life caring for the queen and young. She then graduates to digging and other nest work, and later to defending the nest and foraging. These changes are sometimes fairly sudden, and define what are called temporal castes. An explanation for the sequence is suggested by the high casualties involved in foraging, making it an acceptable risk only for ants who are older and are likely to die soon of natural causes.

Ant species in general have a system in which only the queen and breeding females have the ability to mate. Colonies of these ants are called queen-right.

Some ant nests have multiple queens while others may exist without queens. Workers with the ability to reproduce are called “gamergates” and colonies that lack queens are then called gamergate colonies.

The winged male ants, called drones, emerge from pupae along with the breeding females and these males do nothing in life except eat and mate.

Most ants are univoltine, producing a new generation each year. During the species-specific breeding period, new reproductives, females and winged males leave the colony in what is called a nuptial flight. The males generally fly up into the heavens before the females.

Males then look around to find a common mating ground, for example, a landmark such as a pine tree to which other males in the area converge. Males secrete a mating pheromone that females follow. Females of some species mate with just one male, but in some others they may mate with as many as ten or more different males.

After they mate, females then seek a suitable place to begin a colony. They break off their wings and begin to lay and care for eggs. The females store the sperm they obtain during their nuptial flight to selectively fertilise future eggs.

The first workers to hatch are weak and smaller than later workers, but they begin to serve the colony immediately. They enlarge the nest, forage for food, and care for the other eggs.

Species that have multiple queens may have a queen leaving the nest along with some workers to found a colony at a new site, a process akin to swarming in honeybees.

Anthropomorphized ants have long been used in fables and children’s stories to represent industriousness and cooperative effort.

In the Book of Proverbs in the Bible, ants are held up as a good example for humans for their hard work and cooperation. Note Aesop’s version of this in his fable The Ant and the Grasshopper, a story that I think about quite frequently.

In the Qur’an, Sulayman (Arabic: ???????) is said to have heard and understood an ant warning other ants to return home to avoid being accidentally crushed by Sulayman and his marching army.

In parts of Africa, ants are considered to be the messengers of the deities.

In Hopi mythology, ants are considered as the very first animals.

Ant bites are often said to have curative properties. The sting of some species of Pseudomyrmex is claimed to give fever relief, and ant bites are used in the initiation ceremonies of some Amazon Indian cultures as a test of endurance. (This is an Alex Wild photograph, copyright, all rights reserved.)

Ants communicate with each other using pheromones, sounds, and touch. The use of pheromomes as chemical signals is more developed in ants than in other hymenoptera. Ants perceive smells with their long, thin, and mobile antennae. The paired antennae provide information about the direction and intensity of scents.

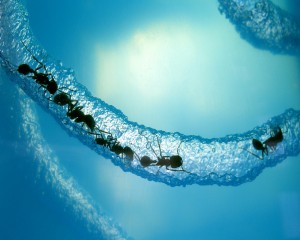

Most ants live on the ground, so they use the soil surface to leave pheromone trails that may be followed by other ants. In species that forage in groups, a forager that finds food marks a trail on the way back to the colony; this trail is followed by other ants, these ants then reinforce the trail when they head back with food to the colony. (Photo copyright: Alex Wild www.alexanderwild.com)

When the food source is gone, no new trails are marked by returning ants and the scent slowly dissipates. When an established path to a food source is blocked by an obstacle, the foragers leave the path to explore new routes. If an ant is successful, it leaves a new trail marking the shortest route on its return. Successful trails are followed by more ants, reinforcing better routes and gradually identifying the best path.

An injured or crushed ant emits an alarm pheromone that sends nearby ants into an attack frenzy and attracts more ants from farther away.

Some ant species use “propaganda pheromones” to confuse enemy ants and make them fight among themselves.

Pheromones are produced by Dufour’s glands, poison glands and glands on the hindgut, pygidium, rectum, sternum, and hind tibia. Pheromones also are exchanged, mixed with food, and passed by trophallaxis, transferring information within the colony.

Trophallaxis (regurgitation) allows other ants to detect what task group (foraging or nest maintenance, for example) to which other colony members belong. (Photo copyright: Dr. Alex Wild www.alexanderwild.com)

In ant species with queen castes, when the dominant queen stops producing a specific pheromone, workers begin to raise new queens in the colony. The latest movement in myrmecology is the study of these pheromones using very delicate instruments.

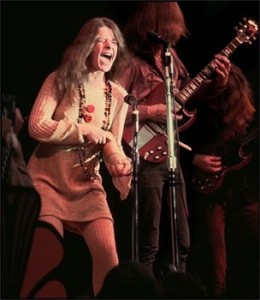

Janis Joplin is stridulating here.

She is rubbing a comb over a ribbed guïro.

If she were doing this quicker and it were a higher pitch, it would sound like a grasshopper, a cricket, a cicada… all stridulating insects. It’s not unlike the most unwelcome of insectual pests, locusts, which are wholly unpleasant and often swarm in the thousands and even millions, as explained here – https://www.evolutiondarlington.com/what-are-locusts-and-why-do-they-swarm/.

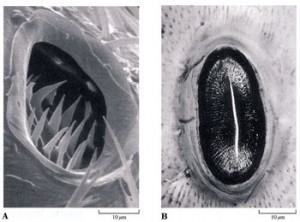

Some ants produce sounds by stridulation, using the gaster segments and their mandibles. Sounds may be used to communicate with colony members or with other species. See how much like a guïro the ant’s sounding board looks?

You can just about hear ant stridulation in one or two species, although you can hear it very well in crickets and cicadas. I have always loved the sound which seems to be hypnotic in the way that chanting is.

Ants stridulate to communicate.

It’s a Ugandan jumping spider who has taken on the ant shape to confuse predators who won’t eat stinging ants. (Alex Wild took this photograph, which is copyrighted: www.alexanderwild.com)

Ants attack and defend themselves by biting and, in many species, by stinging, often injecting or spraying chemicals such as formic acid.

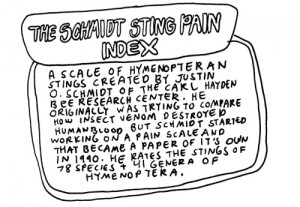

Bullet Ants (Paraponera) in Central and South America, are considered to have the most painful sting of any insect, although it is usually not fatal to humans. This sting is given the highest rating on the Schmidt Sting Pain Index.

The sting of Jack jumper ants (less than a centimeter long with bright orange pincers) can be fatal and an antivenom has been developed for it.

Fire Ants (Solenopsis) are unique in having a poison sac containing piperidine alkaloids. Their stings are painful and can be dangerous to hypersensitive people.

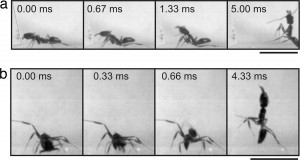

Trap-jaw ants of the genus Odontomachus are equipped with mandibles called trap-jaws, which snap shut faster than any other predatory appendages within the animal kingdom.

One study of Odontomachus bauri recorded peak speeds of between 126 and 230 km/h (78 – 143 mph), with the jaws closing within 130 microseconds on average.

The ants were also observed to use their jaws as a catapult to eject intruders or fling themselves backward to escape a threat.

Before striking, the ant opens its mandibles extremely widely and locks them in this position by an internal mechanism. Energy is stored in a thick band of muscle and explosively released when triggered by the stimulation of sensory organs resembling hairs on the inside of the mandibles. The mandibles also permit slow and fine movements for other tasks.

Trap-jaws also are seen in the following genera: Anochetus, Orectognathus, and Strumigenys, plus some members of the Dacetini tribe, which are viewed as examples of convergent evolution. (Photo: Alex Wild. All rights reserved.)

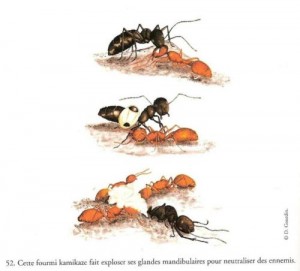

A Malaysian species of ant in the Camponotus cylindricus group has enlarged mandibular glands that extend into their gaster. When disturbed, workers rupture the membrane of the gaster, causing a burst of secretions containing acetophenones and other chemicals that immobilize small insect attackers. The worker subsequently dies.

Suicidal defences by workers are also noted in the Brazilian ant Forelius pusillus where a small group of ants leaves the security of the nest after sealing the entrance from the outside each evening.

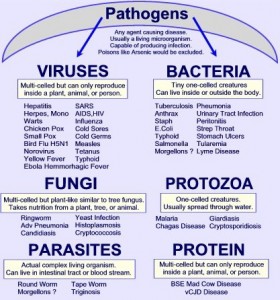

In addition to defence against predators, ants need to protect their colonies from pathogens.

Some worker ants maintain the hygiene of the colony and their activities include necrophory (undertaking), the disposal of dead nest-mates.

Oleic acid has been identified as the compound released from dead ants that triggers necrophoric behavior in Atta mexicana while workers of Linepithema humile react to the absence of characteristic chemicals (dolichodial and iridomyrmecin) present on the cuticle of their living nestmates to trigger similar behavior.

Nests may be protected from physical threats such as flooding and overheating by elaborate nest architecture.

Workers of Cataulacus muticus, an arboreal species that lives in plant hollows, respond to flooding by drinking water inside the nest, and excreting it outside.

Camponotus anderseni, which nests in the cavities of wood in mangrove habitats, deals with submergence under water by switching to anerobic respiration.

Many animals can learn by imitation, but ants may be the only group besides mammals where interactive teaching has been observed. (Photo: Alex Wild www.alexanderwild.com)

An experienced forager of Temnothorax albipennis will lead a new nest-mate to freshly discovered food by the process of tandem running.

The leading tutor teaches the follower. The leader is acutely sensitive to the progress of the follower and slows down when the follower lags and speeds up when the follower gets too close.

Experiments with colonies of Cerapachys biroi suggest that an individual may choose nest roles based on her previous experience.

A generation of identical workers was divided into two groups whose outcome in food foraging was controlled. One group was continually rewarded with prey, while it was made certain that the other failed. As a result, members of the successful group intensified their foraging attempts while the unsuccessful group ventured out fewer and fewer times. A month later, the successful foragers continued in their role while the others had moved to brood care.

Ants generally build complex nests, but some species are nomadic and do not build permanent structures.

Ants may form underground nests or build them in trees. These nests may be found in the ground, under stones or logs, inside logs, hollow stems, or even acorns.

Materials used for construction include soil and plant matter, and ants carefully select their nest sites.

Temnothorax albipennis avoid sites with dead ants since these may indicate the presence of pests or disease. They are quick to abandon established nests at the first sign of threats.

The army ants of South America and the driver ants of Africa do not build permanent nests, but instead, alternate between nomadism and stages where the workers form a temporary nest from their own bodies, by holding each other together. This is called a bivouac. (Photo copyright: Alex Wild www.alexanderwild.com)

The weaver ants (Oecophylla) build nests in trees by attaching leaves together, first pulling them together with bridges of workers and then inducing their larvae to produce silk as they are moved along the leaf edges. Some species of Polyrhacis nest similarly.

Other ant species build nests in and on buildings. Interior spaces in walls, windows, and even electric appliances such as clocks, lamps, and radios in the interior of buildings may be used as sites for nests.

Ants are usually predators, scavengers, and indirect herbivores, but a few have evolved specialised ways of obtaining nutrition.

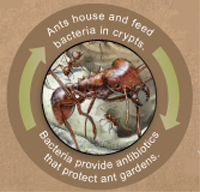

Leafcutter ants (Atta and Acromyrmex) feed exclusively on a fungus that grows only within their colonies. They collect leaves which are taken to the colony, cut into tiny pieces and placed in fungal gardens.

The largest of these ants cut stalks, smaller workers chew the leaves and the smallest tend the fungus. Leafcutter ants are sensitive enough to recognise the reaction of the fungus to different plant material, apparently detecting chemical signals from the fungus.

If a particular type of leaf is found to be toxic to the fungus, the colony will no longer collect it. The ants feed on structures produced by the fungi called gongylydia. The white clumps are gongylydia.

Symbiotic bacteria on the exterior surface of the ants produce antibiotics that kill bacteria introduced into the nest that may harm the fungi.

Ants when they forage for food travel distances of up to 200 metres (700 ft) from their nest and scent trails allow them to find their way back even in the dark.

Day-foraging ants in hot, dry places can easily die from the heat, so the ability to find the shortest route back is essential.

Diurnal desert ants of the genus Cataglyphis (Sahara desert ants, for example) navigate by keeping track of direction as well as distance travelled. Distances travelled are measured using an internal pedometer that keeps count of the steps taken and also by evaluating the movement of objects they see.

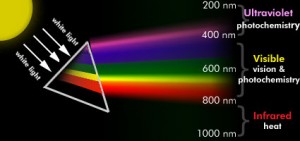

Ants measure direction by using the position of the sun.

They can also make use of visual landmarks when available as well as olfactory and tactile cues to navigate.

Some species of ant are able to use the earth’s magnetic field for navigation. The compound eyes of ants have cells that detect polarised light from the Sun, which is used to determine direction.

These polarization detectors are sensitive to the ultraviolet region of the light spectrum.

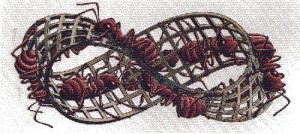

In some army ant species, a group of foragers who become separated from the main column sometimes may turn back on themselves and form a circular ant mill. The workers may then run around continuously until they die of exhaustion.

Such wheels have been observed in other ant species, notably when a group has fallen into or been overcome with water, whereby the group rotates in a partially submerged circle on the surface of the water, which might allow for survival of a brief flooding.

Worker ants do not have wings and reproductive females lose their wings after their mating flights. Therefore, unlike their wasp ancestors, most ants travel by walking.

Jerdon’s jumping ant (Harpegnathos saltator) is able to jump by synchronising the action of its mid and hind pairs of legs.

There are several species of gliding ant including Cephalotes atratus; this may be a common trait among most arboreal ants. Ants with this ability are able to control the direction of their descent while falling. (Photo copyright Alex Wild. www.alexanderwild.com)

Some ants can form chains to bridge gaps over water, underground, or through spaces in vegetation.

Some species, such as fire ants, also form floating rafts that help them survive floods. These rafts may also have a role in allowing ants to colonise islands.

Polyrhacis sokolova, a species of ant found in Australian mangrove swamps, can swim and live in underwater nests. Since they lack gills, they go to trapped pockets of air in the submerged nests to breathe.

Ants have different kinds of societies. Bulldog ants are among the biggest of ants. They are eusocial, that is very social, but their behavior is poorly developed compared to other species. Each individual hunts alone, using her large eyes instead of chemical senses to find prey. (Photo: Alex Wild, all rights reserved)

Species such as Tetramorium caespitum attack and take over neighboring ant colonies. Others invade colonies to steal eggs or larvae, which they either eat or raise as workers or slaves.

Amazon ants are incapable of feeding themselves and need captured workers to survive. Captured workers of the enslaved species Temnothorax have evolved a counter strategy, destroying just the female pupae of the slave-making Protomognathus americanus, but sparing the males (who don’t take part in slave-raiding as adults).

Ants know their relatives through their scent, which comes from hydrocarbon-laced secretions that coat their exoskeletons. If an ant is separated from its original colony, it will eventually lose the colony scent. Any ant that enters a colony without a matching scent will be attacked.

(Photo copyright: Alex Wild www.alexanderwild.com)

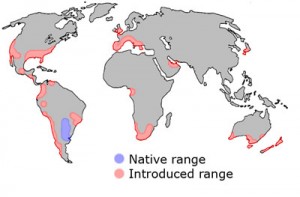

Ants attack each other even if they are of the same species because the genes responsible for pheromone production are different between them. The argentine ant, however, does not have this characteristic, due to lack of genetic diversity, and has become a global pest because of it.

Parasitic ant species enter the colonies of host ants and establish themselves as social parasites; species such as Strumigenys xenos are entirely parasitic and do not have workers, but instead, rely on the food gathered by their Strumigenys perplexa hosts.

This form of parasitism is seen across many ant genera, but the parasitic ant is usually a species that is closely related to its host. A variety of methods are employed to enter the nest of the host ant. A parasitic queen may enter the host nest before the first brood has hatched, establishing herself prior to development of a colony scent. Other species use pheromones to confuse the host ants or to trick them into carrying the parasitic queen into the nest. Some simply fight their way into the nest. (Photo: Alex Wild)

A conflict between the sexes of a species is seen in some species of ants with these reproductives apparently competing to produce offspring that are as closely related to them as possible.

The sperm of the male ant appears to be able to destroy the female DNA within a fertilized egg, giving birth to a male that is a clone of its father. Meanwhile the female queens make clones of themselves to carry on the royal female line.

An extreme of sexual conflict is seen in Wasmannia auropunctata where the queens produce diploid daughters by thelytokous parthenogenesis (giving virgin birth to female clones) and males produce clones by a process whereby a diploid egg loses its maternal contribution to produce haploid males who are clones of the father.

Ants are partners with many other beings including other ant species, other insects, plants, and fungi.

Also, many other animals and even some plants prey upon them.

There are arthropods who spend part of their lives within ant nests, either preying on them, their larvae, their eggs, consuming the food stores of the ants, or hiding from predators. These are inquilines and they may bear a close resemblance to ants. (Alex Wild, photographer, all rights reserved. www.alexanderwild.com)

The nature of this mymyrmecomorphy, ant mimicing, varies, with some cases involving Batesian mimicry where the mimic reduces the risk of predation. (Alex Wild, copyright)

Other cases show Wasmannian mimicry, normally seen only in inquilines. (www.alexanderwild.com copyright Alex Wild)

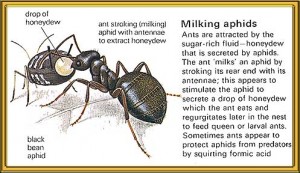

Then, in a sense, ants prey on other animals, sometimes rather benignly. Aphids and other hemipteran insects secrete a sweet liquid called honeydew. The sugars in honeydew are a high-energy food source, which many ant species collect, almost as we collect milk from cows.

The aphids secrete the honeydew in response to ants tapping them with their antennae. The ants in turn keep predators away from the aphids and will move them from one feeding location to another. A human being can tap an aphid with a hair of the head and the same secretion will happen.

Many colonies will take the aphids with them when they move to a new area, thus ensuring a continued supply of honeydew.

Ants also tend mealybugs to harvest their honeydew which can allow mealybugs to become a serious pest of pineapples if ants are present to protect them from their natural enemies.

Ant loving (myrmecophilous) caterpillars of the butterfly family, Lycaenidae (blues, coppers, or hairstreaks) are herded by the ants, led to feeding areas in the daytime, and brought inside the ants’ nest at night.

The caterpillars have a gland which secretes honeydew when the ants massage them. Some caterpillars produce vibrations and sounds that are perceived by the ants.

Other caterpillars have evolved from ant-loving to ant-eating: these myrmecophagous caterpillars secrete a pheromone that makes the ants act as if the caterpillar is one of their own larvae. The caterpillar is then taken into the ant nest where it feeds on the ant larvae.

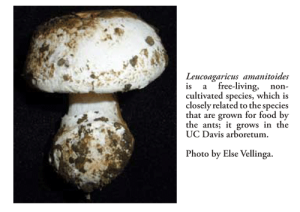

The tribe Attini, fungus growing ants, which includes leafcutters cultivates certain species of fungus in the Leucoagricus or Leucoprinus genera of the Agariceae family.

The ants and the fungus depend upon each other for survival.

The ant Allomerus decemarticulatus has evolved a three-way association with the host plant, Hirtella physophora (Chrysobalanaceae), and a sticky fungus which is used to trap their insect prey. Comme d’habitude dans les dossiers sur les espèces on s’attaque à celles qui ont quelque chose d’époustouflant voir d’extraordinaire et bien les Allomerus decemarticulatus sont extraordinaires dans le fait qu’elles construisent des pièges qui leur servent à attraper leurs proies. (As usual with species one is attracted to those who are somewhat bizarre or even extraordinary and Allomerus decemarticulatus are extraordinary in that they build traps for catching their prey.)

C’est une fourmi arboricole qui creuse des petits trous appelés “domaties” dans les branches d’une plante.

Les fourmis attendent à l’entrer de ces trous un insecte y mettant ses pattes … Et l’attrapent ! (Allomerus decemarticulatus is a tree ant who digs little holes called “domaties” in the branches of a plant, Hirtella physophora. The ants wait by the entry to these holes and when the insect puts its legs there… they catch it!).

Lemon ants make devil’s gardens by killing surrounding plants with their stings and leaving a pure patch of lemon ant trees, (Duroia hirsuta).

This modification of the forest provides the ants with more nesting sites inside the stems of the Duroia trees.

Although some ants obtain nectar from flowers, pollination by ants is somewhat rare. Some plants have special nectar exuding structures, extrafloral nectaries that provide food for ants, who in turn protect the plant from more damaging insects. (Photo: Alex Wild)

Species such as the bullhorn acacia (Acacia cornigera) in Central America have hollow thorns that house colonies of stinging ants (Pseudomyrmex ferruginea) who defend the tree against insects, browsing mammals, and epiphtic vines.

Studies suggest that plants also obtain nitrogen from the ants. In return, the ants obtain food from protein- and lipid-rich Beltian bodies. (Photo: Alex Wild www.alexanderwild.com)

Another example of this type of ectosymbiosis comes from the Macaranga tree, which has stems adapted to house colonies of Crematogaster ants.

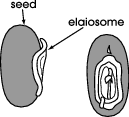

Seed dispersal by ants (myrmecochory) is widespread and estimates suggest that nearly 9% of all plant species may have such ant associations. The ants are collecting a protein rich material attached to the seed. They do not eat the actual seed, which is later discarded in the ant midden. This makes a perfect seedbed. This symbiotic relationship is called myrmecochory.

Elaiosomes (Greek élaion “oil” and sóma “body”) are fleshy structures that are attached to the seeds of many plant species. The elaiosome is rich in lipids and proteins and may be variously shaped. Many plants have elaiosomes that attract ants, which take the seed to their nest and feed the elaiosome to their larvae. After the larvae have consumed the elaiosome, the ants take the seed to their waste disposal area, which is rich in nutrients from the ant frass and dead bodies, where the seeds germinate. (Photograph: Alex Wild www.alexanderwild.com)

Some plants in fire-prone grassland systems are particularly dependent on ants for their survival and dispersal because the seeds are transported to safety below the ground.

A convergence (mimicry?), is seen in the eggs of stick insects. They have an edible elaiosome-like structure and are taken into the ant nest where the young hatch.

Most ants are predatory and some prey on and obtain food from other social insects including other ants. Some species specialise in preying on termites (Megaponera and Termitopone) while a few Cerapachyinae prey on other ants. While no one is sad to see the demise of termites thanks to the ants, ants aren’t particularly welcome either and are both pests most people will want to rid their properties of – you can view website of specialist exterminators and get in touch with them to begin this process.

Some termites, including Nasutitermes corniger, form associations with certain ant species to keep away predatory ant species.

The tropical wasp Mischocyttarus drewseni coats the pedicel of its nest with an ant-repellant chemical. (The pedicel is the part at the top that attaches the nest to a tree or a building.) It is suggested that many tropical wasps may build their nests in trees and cover them to protect themselves from ants.

Stingless bees (Trigona and Melipona) use chemical defences against ants.

Stingless bees, sometimes called meliponines, are a large group of bees (approximately 500 species) belonging in the family Apidae, and are closely related to common honey bees, carpenter bees, orchid bees and bumblebees. Their name is slightly misleading as male bees and bees of other species, such as those in the family Andrenidae, can not sting. Meliponines have stingers, but they are highly reduced and cannot be used for defense.

Flies in the Old World genus Bengalia (Calliphoridae) prey on ants and are kleptoparasites, snatching prey or brood from the mandibles of adult ants.

Wingless and legless females of the Malaysian phorid fly (Vestigipoda longiseta) live in the nests of ants of the genus Aenictus and are cared for by the ants. Most of what you see in the lower of the two photoes above are larvae of army ants of the genus Aenictus. The odd one out is the whiter ‘larva’ in the centre-which is not a larva at all, but a fully adult female of the phorid fly Vestigipoda longiseta.

Fungi in the genera Cordyceps and Ophiocordyceps infect ants. Ants react to their infection by climbing up plants and sinking their mandibles into plant tissue. The fungus kills the ants, grows on their remains, and produces a fruiting body. It appears that the fungus alters the behaviour of the ant to help disperse its spores in a microhabitat that best suits the fungus. This behavior is induced when the fungus takes partial control over the ant’s brain. (Photo: Alex Wild www.alexanderwild.com)

Strepsipteran parasites also manipulate their ant host to climb grass stems, to help the parasite find mates.

A nematode (Myrmeconema neotropicum) that infects canopy ants (Cephalotes atratus) causes the black-coloured gasters of workers to turn red. The parasite also alters the behaviour of the ant, causing them to carry their gasters high. The conspicuous red gasters are mistaken by birds for ripe fruits such as Hyeronima alchorneoides and eaten. The droppings of the bird are collected by other ants and fed to their young, leading to further spread of the nematode. (Photo: Alex Wild)

South American poison dart frogs in the genus Dendrobates (tree climbers) feed mainly on ants, and the toxins in their skin may come from the ants.

This Central American species (Dendrobates) occurs from southeastern Nicaragua to northwestern Colombia. Though mostly distributed in humid lowlands and premontane rainforests from 0-800 m elevation, some montane morphs can be found up to 1200 m elevation. Type locality is the Pacific island of Taboga in the Bay of Panamá. In 1932, that morph was introduced to the Hawaiian Island of O’ahu.

Army ants forage in a wide roving column, attacking any animals in that path that are unable to escape. The name army ant (legionary ant, marabunta) applied to over 200 ant species, in different lineages, due to their aggressive predatory foraging groups, known as “raids”, in which huge numbers of ants forage simultaneously over a certain area, en masse.

Another shared feature is that, unlike most ant species, army ants do not construct permanent nests; an army ant colony moves almost incessantly over the time it exists. All species are members of the true ant family, but several groups have independently evolved the same basic behavioral and ecological syndrome. This syndrome is often referred to as “legionary behavior”, and is another example of convergent evolution. (Photo: Alex Wild www.alexanderwild.com)

In Central and South America, Eciton burchellii is the swarming ant most commonly attended by “ant-following” birds such as antbirds and woodcreepers. The objective of the army-ant-following birds is simple: to devour the grasshoppers, katydids, crickets and other insects that think they are escaping death by flying away from the swarm.

Birds indulge in a peculiar behaviour called anting that, as yet, is not fully understood. Here birds rest on ant nests, or pick and drop ants onto their wings and feathers; this may be a means to remove ectoparasites from the birds.

Anteaters, aardvarks, pangolins, echidnas, and numbats have special adaptations for living on a diet of ants. These adaptations include long, sticky tongues to capture ants and strong claws to break into ant nests.

Brown bears (Ursus arctos) have been found to feed on ants. About 12%, 16%, and 4% of their fecal volume in spring, summer, and autumn, respectively, is composed of ants.

The life of ants is as strange as anything in science fiction. They are fascinating animals. During the writing of this I have imagined myself as an ant being raised from an egg in a colony. I have dreamed that I became an ant.

Thank you and I’ll see you next week.

_______________________________