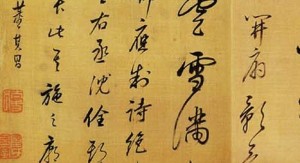

The Chinese very early saw that a sophisticated, loose and elegant style of writing was a clear sign of intellectual prowess and ethical refinement.

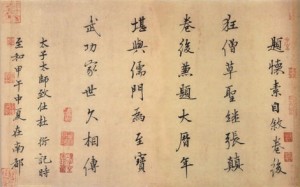

The written language has changed very little from its origins more than three thousand years ago. There are several characters here that are written the same way they are today.

All of the countries around China, Japan, Korea, Viet Nam, Singapore, saw her as the Middle Country, the giant in their midst, so that even today China may be written as the “center.” Center country.

See how the line is drawn through the center of the rectangle on the left?

There are other ways to write “China” but this is the one that is easiest and most often used.

“Sun” was originally drawn as a circle with a dot in the middle, and it evolved into this character.

And this is moon.

Putting the sun and moon together made a brilliant light, so the meaning of this combination of sun and moon is “bright, enlightened” (ming).

You can see the word “ming” on this coin. The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) was a brilliant time of exploration, new ideas.

This means “bright mirror still water.” It is a four character summary of a Chinese Taoist text used for meditation in Zen Buddhism to suggest a calm and clear state of mind. The first character is ming which can be mei in Japanese. Meikyoo shisui.

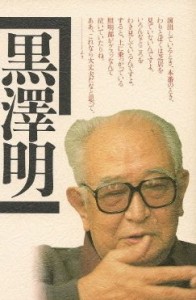

When ming is used in Japanese as a given name, it can be pronounced Akira and it is the “first” name of director Kurosawa Akira.

This character ben is a pictograph of a tree with the root emphasized. It means root, origin, source.

When the root character is put together with the character for sun, it means Japan, the origin of the sun because to the Chinese Japan was to the east and so was the land of the rising sun. In Japanese these characters are pronounced Nihon. Sun root.

Míng bái means “understand” or “clear.” The second character means “white, bright, clear.”

This is how the character for woman evolved.

And this is child. See how her arms are stretched out?

The Chinese write woman and child together to mean good (hao).

This is how you say “hello” in Chinese: Ni hao. You good?

If you put woman under a roof, the meaning is peace, tranquility.

If you put a child under a roof, the meaning is “letter,” because children learned their letters under a roof.

If you put a pig under a roof, the meaning is “family” or “home.”

Putting a woman next to a home is the Chinese way of writing “to marry a man.”

A woman with a broom is a wife.

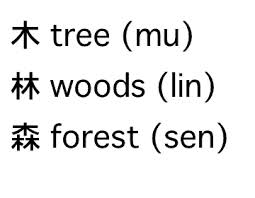

The character for tree or wood is very straightforward.

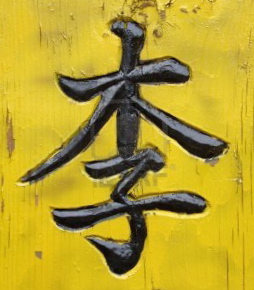

A child under a tree is how Chinese write “plum.”

This character plum is pronounced LI (lee). It is the second most common surname in China, but the most common surname on planet Earth, because we have many Lees here and they have many, many Lees there.

Two trees are a wood and three trees mean “forest.”

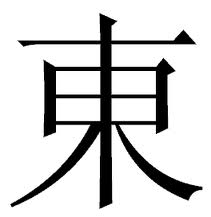

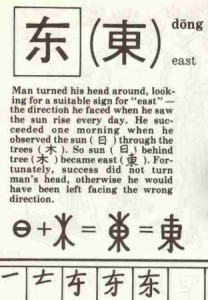

When you see the sun rise through a tree, that means “east.”

The Chinese have simplified their written language so that the character to the left above is how “east” is written today. Traditionalists like me regret the passing of the old beautiful ways, but we have to recognize that this makes life simpler for a billion plus people. You do lose a sense of the etymology of the words, though. It is rather as if in English we would spell history histree thus losing the idea of “story.”

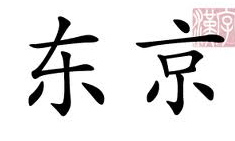

Tokyo means “east capital,” and the Japanese write it like this.

But the Chinese now write it like this.

You know what I mean? We lose a bit of history here.

“West” (xi) was originally a drawing of a nest because birds nest when the sun goes down. This still looks a bit like a bird in a nest, doesn’t it?

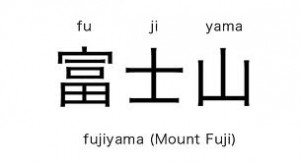

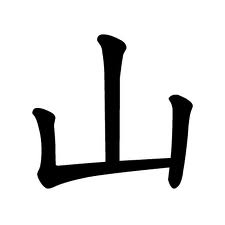

“Mountain” is a drawing of a mountain. Shang. Shan.

There is a province in China called Shanxi. Now you know why it is called that. Because it is a mountain in the west.

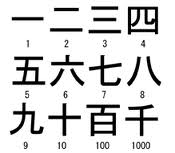

North East South West

The Japanese pronounce mountain “san” and their beautiful mountain is called Fujisan. ”Yama” is the native Japanese word for “mountain,” so they say Fujiyama or Fujisan, but never Fujiyamasan, as I said when I first went to Japan at age six. I was saying Mount Mount Fuji in effect. Rather like someone saying “We’re going to the El Sombrero tonight.”

When the Japanese adopted the Chinese writing there was trouble making a fit, because Chinese is an extremely analytical language and Japanese is as inflected as Latin, so the Japanese created no less than three different systems of writing so they could add endings and prefixes to Chinese words.

Adding to the complexity was the fact that the Japanese often adopted the Chinese word as well as the writing of it, so that there are many, many pairs like “yama” and “san” in Japanese. Almost every noun, it seems, has a native Japanese word and then a Chinese borrowed word for its name.

The character for child above is called zi in Chinese, as we have seen, but in Japanese it can be SHI, SU, ko, -go and most nouns have this many pronunciations.

This character, by the way, is the ending for women’s names which was very common until the advent of womens’ liberation. Women were called Yuriko, Yukiko, Hanako, Yoko, Chisuko, Tomiko, where the -ko was written with this character which means “child.” Now many women have dropped this -ko.

My friend Yukiko made this beautiful flower arrangement.

This character for heart is a fairly accurate anatomical drawing of the heart and it is pronounced xin in Chinese. In Japanese the pronunciation is SHIN, close enough to xin. The native word in Japanese for heart is kokoro and -gokoro in combinations.

This is the old way of writing “love” in Chinese and the Japanese still write it this way. Note that heart is there in the middle of the character which is pronounced ai in Chinese.

In China they now write “love” this way, so it lost its heart.

Too bad.

Here are some “heart” words. This one is “think, recall,” pronounced SHI, omo(u) in Japanese.

“Bad, evil.” Pronunced AKU, waru(i) in Japanese.

“Breath.”

“Sad, sorrowful.” Pronounced bei in Chinese and HI, kanashii in Japanese. The top part of this character means “not,” so not heart = sad.

Grass or herb can be written this way. The line at the top of this character with two other lines through it is used in many words relating to plants. This is called “the grass radical.”

The character for young has the grass sign, probably because grass is spring and youth.

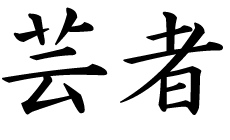

This kanji (kanji = han letter, Chinese letter) is gei which means “art(s),” especially the popular arts like music, weaving, origami, crafts.

A geisha is an art person.

This character also has the grass crown. This is “flower” which is KA or hana in Japanese. When I go to Hana on Maui, I always think of this character because there are so many flowers. The pronunciation is hua in Chinese. This was originally a man falling head over heels with the grass symbol added on top.

This is bamboo. Zhú.

Tea. Chá. You probably know the word chai. Same difference.

Cha iro is Japanese for tea color, brown.

At the top of this character is the “grass” radical and it is used to write this word: plant.

This is the grass radical combined with the character for music which makes the word “medicine.” Grass (herb) and music to mean medicine gives an insight into the Chinese view of healing at the time this character was formulated.

The Chinese write “brave” or “hero” this way to imply that the person is in the jungle (grass component) in a large space.

Because the pronunciation is “ying” they use this character to write England. Ying guó. Brave country. England is a brave country, but the ideogram seems chosen more for its sound than for meaning.

Characters are often chosen for their sounds, especially if they are complimentary.

“America” is called mei koku (beautiful country) in Japan and mei guo in China because those names sound like “America.” Mei guo ren is an American, a beautiful country person.

“Paris” was often written in China with two characters that sound like Pa ri and mean “greatly desire village.” There are a lot of puns and rebuses involved in writing of foreign names.

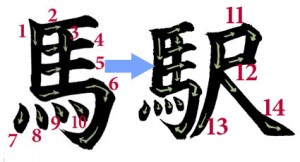

The character for “horse” evolved somewhat like this.

In Chinese this horse character is pronounced ma and in Japanese BA, uma.

Many of the characters for animals have four legs.

This horse radical is used to write to run, to gallop.

This is a station, like a railway station or a bus station. It dates from when horses were the main mode of transportation. Pronunciation is EKI. This is a useful word to be able to read if you live in Japan.

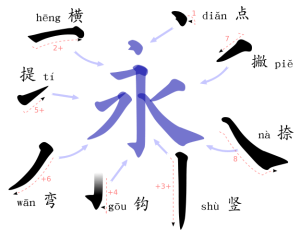

This will give you some idea of the stroke order involved in making these characters. The order of drawing the strokes is very well established. Learning it, I believe, was what led me to become an artist. The stroke order in Chinese writing is logical and well thought out.

In Chinese, fish have legs. Well, they did before the Chinese Communists simplified the written language and did away with legs altogether, replacing them with a single stroke. The Japanese and the people of Taiwan still write the character for fish with the legs.

It evolved in something like this manner.

In China now, “goldfish” is written like this. The character on the left means “gold.” The character on the right is how the Chinese write fish now. One stroke for the old four strokes. More efficient, more convenient, but something is lost.

This is the year of the goldfish.

Person is written like this.

So mermaid or merman is written like this. A person fish.

This is the character for eternity and it contains every kind of stroke used in Chinese calligraphy.

In Japanese for “I am happy,” you can say “Shiawase da.”

The first character on the left is called by the Japanese KOO, saiwa(i), sachi or shiawa(se). It means good fortune or happiness.

If you really want to express happiness, you write the character twice… double happiness.

You see this double happiness character everywhere, especially in San Francisco, because everyone wants to be doubly happy and fortunate.

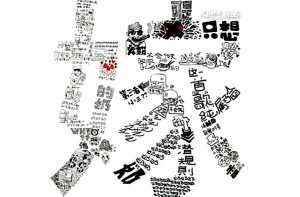

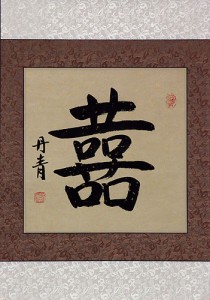

Artists challenge themselves to see how loosely, elegantly and artistically they can make this word double happiness and yet still have it be understoo0d.

Can you still read the two happinesses here?

Of course this is a wonderful message for weddings and anniversaries because there are two characters for two people. Looks a bit like kissing, doesn’t it?

My friend Peggy Pettigrew Stewart is a glass artist and she may want to consider using some variation of this beautiful image in her work.

Double your pleasure, double your fun, double your happiness everyone.

When characters were written on bones and bronze, double happiness looked like this.

Here it is in jade. Can you still read it?

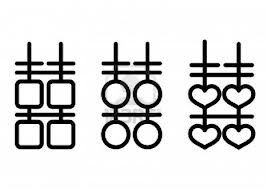

And some modern silly versions.

We’ll see you next week?

_______________________________________