To Ergaleio: sign on a shop in Athens says “The Tool” written out in Greek with tools.

Many, many hand axes have been found in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania.

Such axes were made by Homo Erectus, the first tool making creature.

These people loved making handaxes. They made them for practical use, yes, but also for the sheer creative joy of it. They made hand axes that were far too large for normal use, just because they liked the form. At least that’s what it looks like from this distance. They made Acheulian hand axes in all sizes and varieties. These were the first tools that are recognizable as such.

This is a hand axe that was found near Gray’s Inn Road, London. It is 350,000 years old.

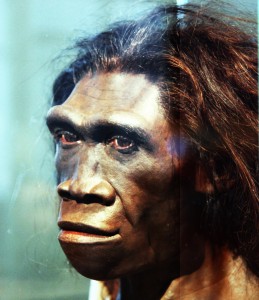

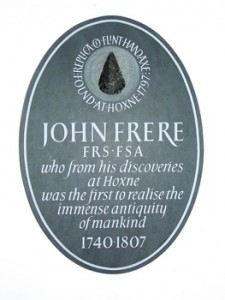

John Frere (10 August 1740 – 12 July 1807) was an English antiquary and a pioneering discoverer of paleolithic tools in association with large extinct animals such as elephants.

He used the Gray’s Inn hand axe and one he found in Hoxne, Suffolk, to illustrate the antiquity of human culture at a time when many people thought the world was 6,000 years old. Actually, many people still do think that the world is 6,000 years old and they carry around misspelled signs to insist upon their belief.

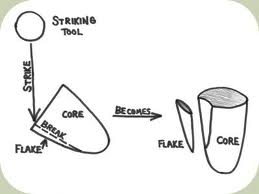

Hand axes were made from flint or any other stone that would take a sharp edge. Flakes were hammered off using another stone, and the flakes themselves were used to make smaller tools such as scrapers and knives.

This is called flint knapping or pressure flaking and it is a technique that can make a tool of great precision and beauty.

About 25,000 years ago, people learned how to control the shape of the flake from the parent block so that long, narrow blades could be made into knives, chisels and gravers.

Maybe those two feet long Acheulian hand axes were made simply as the source for these flake blades.

Bone and antler tools were shaped by abrasion and cutting.

They could be polished with sandstone, so there is ample evidence of several step manufacture here that required planning ahead.

A soft stone could be hollowed out

and a lamp made using animal fat and a wick of twisted vegetable matter.

This is a wooden sickle (Thebes, 1300 BCE) with a flint blade in the shape of a cattle jawbone. Perhaps jawbones were originally used to harvest cereal crops.

The silica in the strong stems of the crop often wore down the flints, leaving behind a deposit or gloss.

A tool kit from 14,000 years ago could contain a sickle for harvesting wild wheat or barley, a cluster of flint spearheads, a flint core for making more spearheads, some smooth stones (maybe slingshots), a large stone for striking flint pieces off the flint core, a cluster of gazelle toe bones which were used to make beads. Leaves and herbs were often carried as medicine.

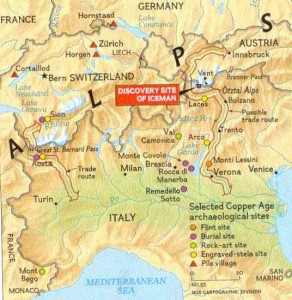

Remember Ötzi who was found in the ice in Italy near Bolzano?

He is a well-preserved natural mummy of a man who lived about 5,000 years ago. The mummy was found in September 1991 in the Ötztal Alps (hence Ötzi) near the Similaun mountain and Hauslabjoch on the border between Austria and Italy. He is Europe’s oldest natural human mummy, and has offered an unprecedented view of Chalcolithic Europeans. His body and belongings are displayed in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy.

Seventy objects found with Ötzi. They include a cape of woven grass; a bearskin cap; a goat-hide coat; leather leggings and loincloth; shoes with bearskin soles and deerskin uppers, filled with grass; an unfinished longbow, and a deerskin quiver containing 14 arrows (only two of which were finished); a backpack frame of hazel and larchwood; a copper axe with a wooden haft and leather bindings; a dagger with a flint blade and an ashwood shaft in a woven grass sheath; and some containers of sewn birchbark.

The axe’s haft is 60 centimeters (24 in) long and made from carefully worked yew with a right-angled crook at the shoulder, leading to the blade.

The 9.5 centimetres (3.7 in) long axe head (blade) is made of almost pure copper, produced by a combination of casting, cold forging, polishing, and sharpening. It was let into the forked end of the crook and fixed there using birch tar and tight leather lashing. The blade part of the head extends out of the lashing and shows clear signs of having been used to chop and cut. At the time, such an axe would have been a valuable possession, important both as a tool and as a status symbol for the bearer.

Ötzi’s knife measured 5.2 in in total length. The handle was made of ash, the blade was flint and the sheath of woven lime wood bast. A string was attached to the back of the knife.

Ötzi also had a tool designed for flint knapping, also called a retoucher, because one could pressure flake the knife blade or the projectile points with it, and so sharpen them.

It consisted of a piece of lime tree branch, which was pointed on one side. On the pointed side a hole was drilled, into which a bone plug (stag antler) was inserted with which the knapping was done.

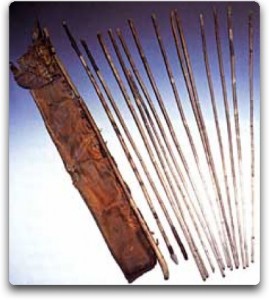

A quiver of arrows was also discovered alongside Ötzi. It was made of leather, and held 14 arrows made of viburnum sapwood. Two of the arrows were completed. They had flint tips, held with birch tar and bindings. The other 12 arrows were unfinished. In the quiver several pieces of antler were also discovered.

Ötzi was also carrying an unfinished yew bow. The stave was 72 inches long.

Ötzi also carried two birch bark containers possibly used to carry some other items. They were about 5.9 in to 6.0 inches in diameter and about 7.8 inches in height. They were stitched together using tree fiber. Tests have shown that one of them contained maple leaves as well as spruce needles and charcoal, probably an ember for fire making. The leaves were most likely medicinal.

He had a long belt with a pouch on the side. In the pouch he had several flakes of flint, a 2.8 in long bone awl, and a small drill. The majority of the pouch was filled with tinder fungus. Some traces of iron pyrites were also found, indicating that he was perhaps using a flint and steel method of fire lighting. We will leave Ötzi for now, but I plan to see him when I next pass through Bolzano.

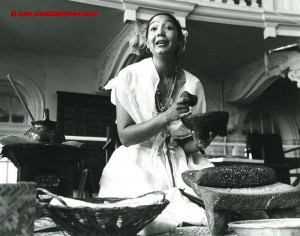

This is a metate, also referred to as a “piedra de moler” (grinding stone), this tool is related in lineage to the molcajete, and was used by the Mayans and Aztecs.

The metate is used to grind corn and for mashing ingredients to make salsas, purees, and chocolate. La mano is the cylindrical part that you hold in your hands.

There is an idiom in Mexican Spanish, “Echar comal y metate” which literally could mean “throw the tortilla oven and the corngrinder,” but it really means what we mean when we say “chew the fat.” It means chismear which is to gossip. It would be natural to do a lot of talking while grinding and baking.

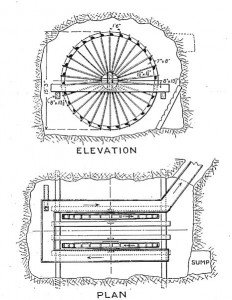

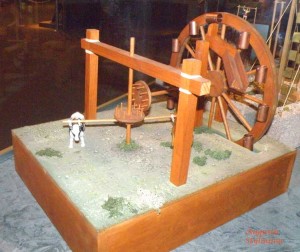

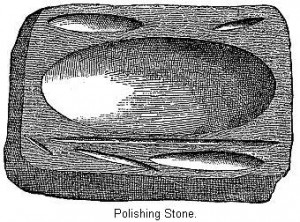

A quern is a hand-mill for grinding corn or other grains. The simplest kind consists of a large stone with a cavity in the upper surface to contain the corn which is then pounded, rather than ground, by a smaller stone.

The more usual form of quern consists of two circular flat stones, the upper one pierced in the centre, and revolving on a wooden pin inserted in the lower. A handle is attached to the outer edge and used to turn the stone while corn is dropped into the central opening.

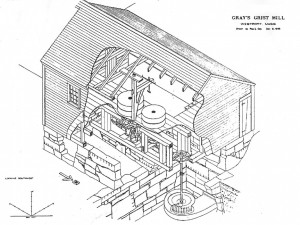

Millstones come in pairs. The base or bedstone is stationary. Above the bedstone is the turning runner stone which actually does the grinding.

The runner stone spins above the stationary bedstone creating the “scissoring” or grinding action of the stones.

A runner stone is generally slightly concave, while the bedstone is slightly convex. This helps to channel the ground flour to the outer edges of the stones where it can be gathered up.

The runner stone is supported by a cross-shaped metal piece (rind or rynd) fixed to a “mace head” topping the main shaft or spindle leading to the driving mechanism of the mill which can be powered by wind, water, animal, man.

The Greeks invented the two main components of watermills, the waterwheel and toothed gearing, and were the first to operate undershot, overshot and breastshot waterwheel mills.

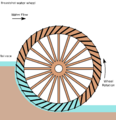

Undershot water wheel developed for watermilling since the 1st century BCE.

Overshot water wheel used for watermilling also since the 1st century BCE.

Breastshot water wheel used for watermilling since the 3rd century CE.

The first water-driven wheel is probably the Perachora wheel (3rd c. BCE), in Greece.

The earliest written reference is in the technical treatises Pneumatica and Parasceuastica of the Greek engineer Philo of Byzantium(ca. 280?220 BC).

Those portions of Philo of Byzantium’s mechanical treatise which describe water wheels and which have been previously regarded as later Arabic interpolations, actually date back to the Greek 3rd century BCE original.

The sakia gear is, already fully developed, for the first time attested in a 2nd century BCE Hellenistic wall painting in Ptolemaic Egypt.

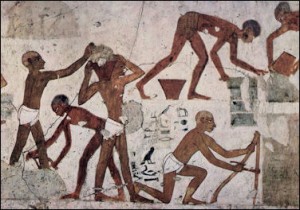

People needed to clear the land for crops, so you would think that the earliest dwellings would be made of timber.

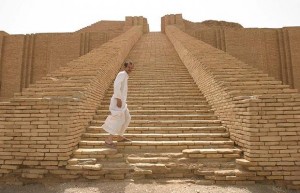

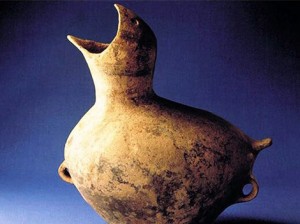

In Mesopotamia, however, the earliest building material was sun-dried brick bricks which before 5,000 BCE were molded by hand and looked like stones or even loaves of bread.

Brick molds were made very early.

Mud in almost liquid form was packed down into the molds which were then removed so that the new brick could sit in the hot sun to dry.

Brick molds were used at least as far back as 6,000 BCE in Anatolia (Turkey).

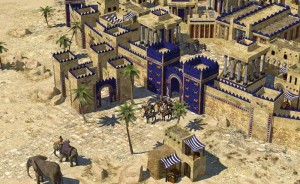

And now I must describe how the soil dug out to make the moat was used, and the method of building the wall. While the digging was going on, the earth that was shoveled out was formed into bricks, which were baked in kilns as soon as sufficient number were made; then using hot bitumen for mortar, the workmen began at revetting the brick each side of the moat, and then went on to erect the actual wall. In both cases they laid rush-mats between every thirty courses of bricks. – Herodotus, i. 179 (of Babylon). The method of making bricks used to take days, but thanks to companies that supply cement brick machine, what used to take days now takes just a few hours.

The floor of the dwelling was made of a carefully laid layer of clay and it was soon discovered that clay could be hardened by firing which ushered in the age of pottery.

The earliest cooking vessels were probably made of wood or a hollowed out stone or gourds or shells.

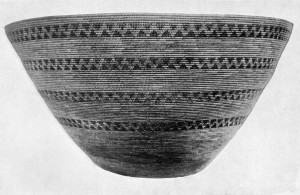

Right up into the 19th century, native Americans like the Miwoks of the San Francisco bay area boiled water in tightly woven baskets for the processing of acorns.

The earliest pottery we know already shows advanced techniques such as the addition of sand or crushed rock to prevent shrinkage during drying and also to prevent breakage.

Potters seldom used just one clay mixture and they paid a great deal of attention, of course, to the properties of the finished product.

People had burnished the walls and floors of their brick and clay houses and they likewise burnished their pottery by rubbing it with a stone.

In the beginning, a base of the pot was molded over a shape of a hemisphere, perhaps the bottom of an old pot, and then rings of clay were added.

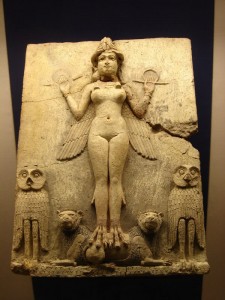

The first potter was the sumerian-babylonian Aruru the great, the almighty gentle mother god of the earth and birth, who created humanity from clay. She molded mankind out of clay using a god as pattern and breathed life into him with her divine exhalation. In Sumerian mythology, Aruru (also known as Ninmah, Nintu, Ninhursaga, Belet- ili or Mami) was the almighty mother goddess of the earth and birth.

She created the first man out of clay (adamah = the female soil). She confected seven mother-vessels for women and seven for men. « The shapes of humanity are formed by Aruru » as say the Assyrians.

This is the Sumer tree of life (qaballah). In Sumerian and Babylonian mythology, Adamu was the first man.

The gods tricked Adamu and his descendants out of immortality – not wanting man to be immortal like the gods – by telling him that the magic food of eternal life was poisonous to him, and as such Adamu didn’t eat it and so didn’t become immortal.

The word “ceramics” comes from the Greek keramikos (?????????), meaning “pottery”, which in turn comes from keramos (???????), meaning “potter’s clay.” This is the Ishtar gate which is made of glazed ceramics.

The Ishtar gate is now at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

The potter’s wheel was probably invented in Mesopotamia by the 4th millennium BCE.

The oldest pottery vessels come from East Asia, with finds in China and Japan, then still united by a land bridge, from between 20,000 and 10,000 BCE, although the vessels were simple utilitarian objects. This pottery fragment is from a layer dating approximately 20,000 years old in the Xianrendong cave in south China’s Jiangxi province.

For thousands of years, small ceramic lamps were used to illuminate homes and temples. Hundreds of these lamps have been excavated, most of which are no more than a simple saucer-like vessel. Earlier lamps were wheel-thrown, while later lamps were formed from clay rolled into a sheet and pressed into a mold. Wicks were generally made of flax or hemp and were draped over the edge of the lamp. Olive oil was the preferred fuel, but other vegetable, nut and animal oils were also used.

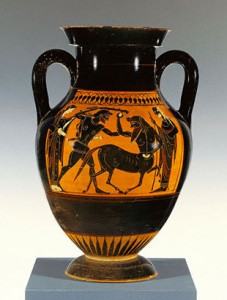

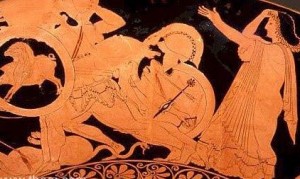

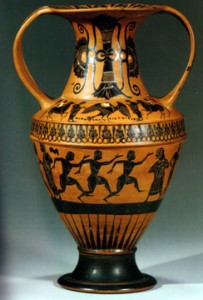

Corinthian and Attic ware was superior to anything being produced in the west at this time and there are several reasons for this.

The potter’s wheel was no longer low and close to the ground. Now it was a large flywheel raised about a foot and a half and was turned by an assistant seated opposite the potter.

Once the object had been shaped and dried it was put back on the wheel, smoothed and shaved to give it a very fine surface.

The red and black were made by a sophisticated process that involved a very fine clay material and an elaborate sequence of firing.

The clay slip that was used for the black was clay, water and an alkali (probably leach from wood ash). This mixture was allowed to stand so that the crude parts sank to the bottom and only the fine particles were suspended and they were poured off and the water evaporated out. This was then used to paint on the pot or plate.

The object was then put in the kiln and fired to around 1000 degrees centigrade when the openings in the furnace were closed which blackened the entire surface of the pot.

When the kiln had cooled down to 800 degrees or so, the apertures were reopened. The areas that had been painted with the slip stayed black but the unpainted parts slowly lost the black and turned red.

This is all easy to say and very difficult to do. There was a lot of trial and error, and only in recent years have potters been able to duplicate this process.

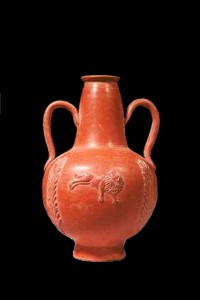

Pottery was produced in enormous quantities in ancient Rome, mostly for utilitarian purposes. It is found all over the former Roman empire and beyond. Monte Testaccio, a huge waste mound in Rome, was made almost entirely of broken amphorae used for transporting and storing liquids and other products, mostly Spanish olive oil, which was landed nearby and used as the main fuel for lamps, as well as for use in the kitchen and washing in the baths.

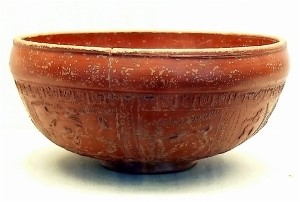

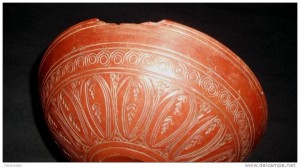

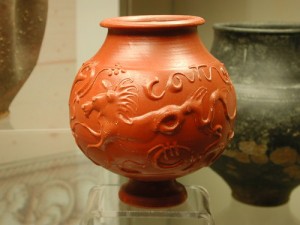

The major class of fine Roman pottery is the red-gloss ware often made in Italy and Gaul and widely traded, from the 1st century BCE to the late 2nd century CE, and traditionally known as terra sigillata.

Sigilla is Latin for the little figures that are, for example, in a cameo ring. There was actually a holiday called Sigillaria where people in Rome exchanged these little figures.

Sigilla is the origin of our word “seal,” probably because of the similarity between a cameo ring and a seal ring. The word sigilla is a Latin plural, but the singular sigillum was never used.

This terra sigillata bowl was made in Valladolid, Spain.

The usual way of making relief decoration on the surface of an open terra sigillata vessel was to throw a pottery bowl whose interior profile corresponded with the desired form of the final vessel’s exterior.

The internal surface was then decorated using individual positive stamps (poinçons), usually themselves made of fired clay, or small wheels bearing repeated motifs, such as the ovolo (egg-and-tongue) design that often formed the upper border of the decoration.

Sometimes the maker used a stylus to add details and embellish the work.

When the decoration was complete in intaglio on the interior, the mould was dried and fired in the usual way, and was subsequently used for shaping bowls. As the bowl dried, it shrank sufficiently to remove it from the mould, after which the finishing processes were carried out, such as the shaping or addition of a foot-ring and the finishing of the rim.

The details varied according to the form. The completed bowl could then be slipped, dried again, and fired.

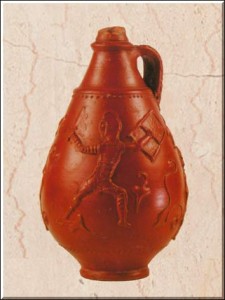

Jugs and jars, were seldom decorated in relief using moulds, though some vessels of this type were made at La Graufesenque by making the upper and lower parts of the vessel separately in moulds and joining them at the point of widest diameter.

Relief-decoration of tall vases or jars was usually achieved by using moulded appliqué motifs (sprigs) and/or barbotine decoration (slip-trailing).

The latter technique was particularly popular at the East Gaulish workshops of Rheinzabern, and was also widely used on other pottery types.

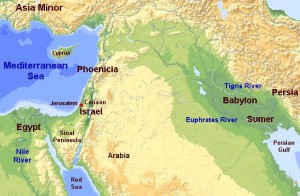

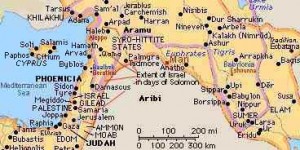

By about 5,000 BCE there were farming villages throughout the Tigris-Euphrates valley, the Levant, Anatolia, mainland Greece and on, perhaps, a few islands in the eastern Mediterranean.

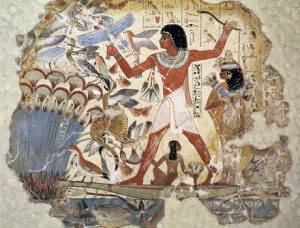

A little after 5,000 BCE in this same area, there came a whole set of technological advances that were to influence the whole life of humankind. People in these early farming communities decorated the walls of their homes. They decorated their tools. They decorated themselves too. There was a sense of liveliness and even of merriment in the culture.

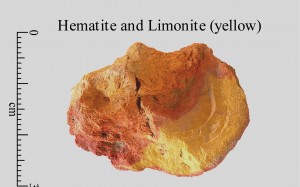

The search was on for colors. Yellow ochre or limonite and red ochre or hematite are ores of iron.

Ores of copper are malachite, the green mineral, and the blue mineral, azurite.

Copper occurs as a metal in ore deposits and it was easy to find the green pigment which was used as eye shadow.

Brightly colored minerals, the red and yellow ochres and the blue and green ores of copper were ground to a fine powder with a mortar and pestle and then using animal fat as a binding medium, people began to make rouge and mascara.

Perhaps the search for these colors is what first led people to find out about copper and iron about seven thousand years ago.

Copper was not like other “stones” that people knew. It couldn’t be chipped or flaked but it could be hammered into shape. Only a little bit of hammering, though, would make the copper brittle and it would break. It was soon found that heating the copper to where it was red hot would allow the metal to be hammered some more and then it could be heated again. This process is called annealing. Annealing is the process by which you heat steel to create different metals and can be one common process when it comes to commercial heat treating of different metals. These different metal-altering processes discovered some time ago, are still commonly used today in various industries. Stainless steal is a by-product of steal which is a great example. There are two methods to heat such a solid metal. But which is better and cost-effective? Is it tempering vs annealing? There are only two documented ways to heat such a material.

Copper the metal is rare in ore deposits and the ore deposits themselves are scarce, and could be found mainly in the mountains of eastern Turkey and Syria, in the Zagros mountains (western Iran), in Sinai, in the mountains of the Arabian desert east of the Nile and on Cyrprus whose very name means “copper.”

Copper occurs as native copper in these places and was known to some of the oldest civilizations on record. It has a history of use that is at least 10,000 years old, and estimates of its discovery place it at 9000 BCE.

A copper pendant was found in northern Iraq that dates to 8700 BC. There is evidence that gold and iron from meteors (but not from iron smelting) were the only metals used by humans before copper.

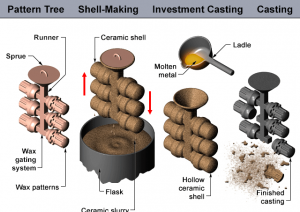

The history of copper metallurgy is thought to have followed the following sequence: 1) hammering and working of naturally occurring copper 2) annealing, 3) smelting, and 4) the lost wax method.

In southeastern Anatolia, all four of these metallurgical techniques appear more or less simultaneously at the beginning of the Neolithic c. 7500 BCE.

Agriculture was independently invented in several parts of the world (including Pakistan, China, and the Americas) and, similarly, copper smelting was invented locally also in several different places.

Smelting was probably discovered independently in China before 2800 BCE, in Central America perhaps around 600 CE, and in West Africa about the 9th or 10th century CE.

Investment casting was invented in 4500–4000 BCE in Southeast Asia. Carbon dating has established copper mining at Alderly Edge in Cheshire UK at 2280 to 1890 BC.

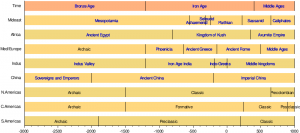

The Bronze Age (bronze is copper with a little bit of tin added) began in southeastern Europe around 3700–3300 BCE, in northwestern Europe about 2500 BCE.

Copper was the metal first used to make tools and weapons. (Remember Ötzi’s axe blade?) Pure copper is, however, soft and not ideally suited to the purpose. It was discovered that, by alloying copper with tin, a much more durable metal could be produced: bronze.

The Bronze Age ended with the beginning of the Iron Age, 2000–1000 BC in the Near East, 600 BC in Northern Europe. The transition between the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age was formerly termed the Chalcolithic period (copper-stone), with copper tools being used with stone tools, but the term has gradually fallen out of favor because in some parts of the world the Calcholithic and Neolithic have the same beginning and end.

Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc, is of much more recent origin. It was known to the Greeks, but became a significant supplement to bronze during the Roman Empire.

Pottery and glass will last through conditions that would soon destroy leather and wood, so we know far more about glass than we do about how leather was used, for example.

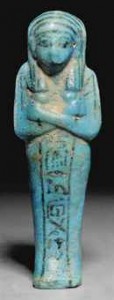

Around 2,000 BCE, Egyptian faïence, the oldest glazed soapstone ornaments, was beginning to be replaced by a completely “synthetic” material, glass.

White sand was mixed with natron, a naturally occurring form of sodium carbonate, and shaped and heated so that the whole mass was fused.

Blue glaze was applied to this synthetic core. The fusion of the quartz and soda with the admixture of a little lime to make the concoction stable is pretty much how we still make glass today.

The Mesopotamian makers didn’t even know that they needed to add lime to ensure a stable glass, because the lime was already there in the other raw materials.

The synthetic (glass) core (for taking the blue glaze) could be overheated and molten and many examples have survived where the heating ceased just before the core melted and became a shapeless form.

It is probable that the discovery of glass came from seeing the faïence and core (glass) melt into a blob too many times.

A little before 2,000 BCE, true glasses appeared in Mesopotamia, but the glassmakers weren’t sure at first just what they had.

Instead of molding the new material while it was hot, they treated glass at first as if it were a precious decorative stone and mostly cut and polished it while it was cold.

There were many experiments and we soon see a small amount of lead in the glazes on the faïence.

The effect of lead in a glaze or a glass is to give it a greater clarity and brilliance. Who was the first person to add lead to glass? We don’t know, but she may have been a potter since she would have been used to adding lead to her ceramics glazes. From about 1,500 BCE on, lead is not used as a metal (which is too soft for weapons and too, er, “ugly” for jewelry) but as an ingredient in glass, pottery and even bronzes. Lead is a medium. Only now, in the first decades of the 21st century are we finally ridding ourselves of this very useful but very poisonous material.

Lead, aside from adding brilliance, materially altered the cooling behavior of the glass. Glass without lead will shrink and crack as it cools, but the addition of a large quantity of lead will significantly decrease shrinkage, allowing the maker to, say, apply a glaze to an earthenware surface.

The Mesopotamians probably became fully aware of the benefits of lead a bit before 1,000 BCE. The Gate of Ishtar has that shining, glorious beauty because the ceramic tiles were glazed with lead.

In Egypt and Mesopotamia (which, always remember, is not a culture but a geographical place of many cultures) glassmaking became increasingly sophisticated.

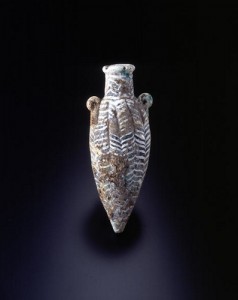

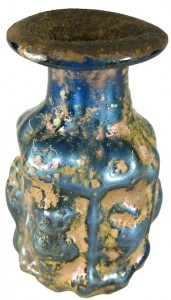

Small glass bottles in both areas were made by dipping a friable core of sand and some organic adhesive into a crucible of molten glass and then the friable core was broken out.

Another way to make a small bottle began with that disposable core and then bits of broken glass and finely ground glass material covered the core. The whole was then inserted into the hot oven for fusion

In both methods the core was extracted at the end of the operation leaving a hollow glass bottle.

Copper ores gave a turquoise hue to the final product, and cobalt blue (another copper ore) gave a darker shade.

Iron ores, as we have seen, provided yellows and reds, and the addition of tinstone resulted in a white, opaque glass.

Threads of differently colored glass could be roped in delicate patterns on the surface of the new object and, while still hot and plastic, could be rolled gently over the flat surface, making beautiful , fluid patterns that would last forever.

The glass unguent bottle was a familiar object in the wealthier homes of Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The small bottles had other uses. In Cyprus, people have found many small glass containers shaped like the dried head of an opium poppy.

Not just any opium poppy, but one that has been slit and bears the scar where the papaverous juice has flowed out to relieve the pains of our passage through this life.

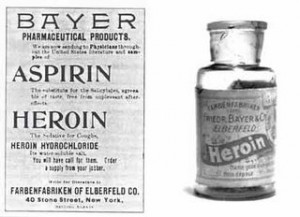

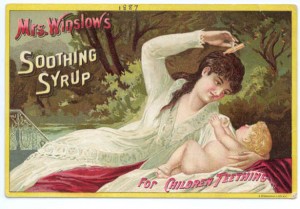

This was the aspirin bottle of that time. Opium was taken, and still is taken, to relieve hangovers, headaches, menstual cramps and a myriad of other ills.

Opium was even used to keep the baby quiet.

Many, many of these scar faced glass bottles have been found in graves to alleviate the longueurs of a passage to another world.

Talking of other worlds, I’m going to visit one now and do some playing.

Bon voyage till next week.

____________________________________________

What a wonderful read! I learned so much.