El español is the first language spoken in twenty countries around the world.

Mandarin Chinese has the most native speakers. Does it surprise you that Spanish has the second most native speakers on the planet? Between 470 and 500 million speak Spanish as a first language.

On the Internet el español is the third most commonly used language after English and Mandarin.

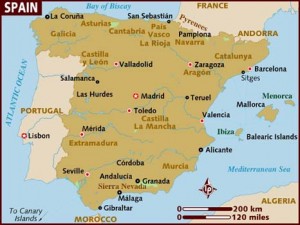

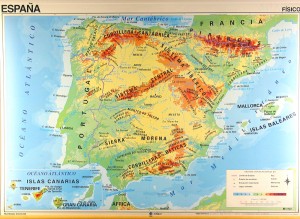

Spanish is the official language of Spain, the country after which it is named and where it originated, and is widely spoken in Gibraltar, although English is the official language there. It is also commonly spoken in Andorra, although Catalan is the Andorran official language. If you ever go to an event such as Competa feria, you’ll find that Spanish is the only language spoken by the natives.

Spanish is spoken in small communities in other European countries, such as the United Kingdom, France and Germany. While there are many people in countries like the UK that know basic spanish describing words, the number of natives that are fluent speakers is much lower. It is an official language of the European Union. Spanish is the native languageof 1.7% of the Swiss population, representing the largest minority after the 4 official languages of Switzerland.

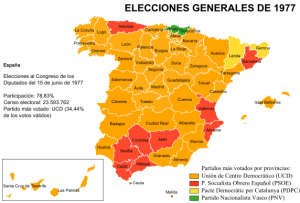

Latin America has the most Spanish speakers. Of all the countries with a majority of Spanish speakers, only Spain and Equatorial Guinea are outside the Americas.

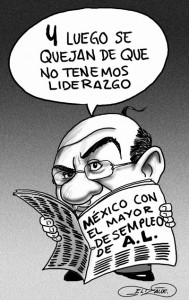

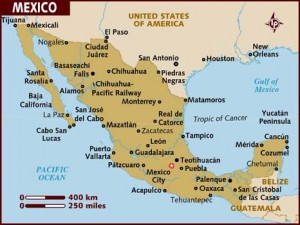

Mexico has the most native Spanish speakers of any country. Spanish is the official language—either in fact or by law—of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Venezuela.

English is the official language of Belize, but Spainish is spoken by 43% of the population there.

Trinidad, Tobago and Brazil have implemented Spanish language teaching into their education systems. In Brazil many border towns and villages (especially in the Uruguayan-Brazilian and Paraguayan-Brazilian border areas), have a mixed language known as Portuñol.

Spanish, also called castellano, is a Romance language that originated in Castilla (Castile), a region of Spain.

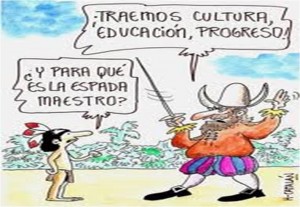

The Ibero-Romance group of languages evolved from several dialects of Latin in the land the Romans called Hispania after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century. It had definitely become a separate language by the ninth century CE and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castilla into central and southern Iberia.

The Spanish vocabulary was influenced by its contact with Basque and by other related Ibero-Romance languages and later absorbed many Arabic words during the seven hundred years that los Moros, the Moors, were in the Iberian Peninsula. Español also adopted many words from non-Iberian languages, particularly Occitan, French, Italian and Sardinian. In modern times, Spanish has adopted and adapted many English words.

Spanish is the most popular second language learned in the US. From the last decades of the 20th century, the study of Spanish as a foreign language has grown significantly, in part because of the growing populations and economies of many Spanish-speaking countries, and the growing international tourism in these countries.

Güero means ‘pale’ in Spanish, so it is a slang word (honky) for a gringo. Canelo means ‘cinnamon,’ and so el güero canelo means ‘cinnamon paleface,’ or, as we would say, ‘strawberry blonde,’ that is, a person with blonde hair tending to red. Sometimes if I see that a server in a coffeeshop is Hispanic, I order a güero doble (a double honky) instead of a double Americano. Sometimes they get it, and sometimes they don’t, but it’s really fun when they do.

Spanish is the most widely understood language in the Western Hemisphere, with significant populations of native Spanish speakers ranging from the tip of Patagonia to as far north as New York, Chicago and Toronto. Since the early 21st century, it has taken the place of French as the second-most-studied language and the second language in international communication, after English.

Spanish, or castellano, the language of the region of Castilla differs from Galician, Basque and Catalan. The Spanish Constitution of 1978 uses the term castellano for the official language of the whole Spanish State, in contrast to las demás lenguas españolas. Article III states:

El castellano es la lengua española oficial del Estado. (…) Las demás lenguas españolas serán también oficiales en las respectivas Comunidades Autónomas…

The Spanish Royal Academy on the other hand, currently uses the term español in its publications but from 1713 to 1923 called the language castellano.

The Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (a language guide published by the Spanish Royal Academy) states that, although the Spanish Royal Academy prefers to use the term español in its publications when referring to the Spanish language, both terms, español and castellano, are regarded as synonymous and equally valid.

The Spanish Royal Academy Dictionary posits two etymologies for the word español: it derives the term from the Provençal word espaignol, and that in turn from the Medieval Latin word Hispaniolus, ‘from—or pertaining to—Hispania’. Other authorities attribute it to a supposed medieval Latin term *hispani?ne, with the same meaning.

The Romans came to Hispania during the Second Punic war (wars with Carthage) beginning in 210 BCE. Previously, Paleohispanic languages not related to Latin were spoken in the Iberian Peninsula. These languages included Basque (still spoken today), Iberian and Celtiberian. Traces of these languages, especially Basque, can be found in the Spanish vocabulary today, mainly in place names.

The first documents (Glosas Elianenses) to record the language that became castellano or español are from the 9th century. The most important influence on the Spanish (Castilian) lexicon came from neighboring Navarro-Aragonese, Leonese, Aragonese, Catalan, Portuguese, Galician, Mirandese, Occitan, Gason and later French and Italian—but also from Basque, Arabic and to a lesser extent the Germanic languages. Many words were borrowed from Latin through the influence of written Latin and the liturgical language of the Church.

Vulgar Latin evolved into español in the north of Iberia, in an area defined by Álava, Cantabria, Burgos, Soria and La Rioja. The dialect was later brought to the city of Toledo, where the written standard of Spanish was first developed, in the 13th century.

Español (castellano) then developed a strongly differing variant from its close cousin, Leonese, and, according to some authors, was distinguished by a heavy Basque influence. This distinctive dialect progressively spread south with the advance of the Reconquista, and so gathered a sizable lexical influence from the Arabic of Andalusia, much of it indirectly, through the Romance Mozarabic dialects.

The written standard for this new language began to be developed in Toledo, in the 13th to 16th centuries, and Madrid, from the 1570s.

Luís Vaz de Camões is the poet of Portugal, so he comes from a place that is vacant on the Spanish map. I just like this drawing, and, not incidentally, his epic poem Os Lusíadas. I will write about Camões later in a web log about the Portuguese language.

The evolution of the sound system in español from Vulgar Latin is echoed by similar changes in other Western Romance languages, including lenition (softening) of intervocalic consonants (thus Latin v?ta ? Spanish vida).

The diphthongization of Latin stressed short e and o—which occurred in open syllables in French and Italian, but not at all in Catalan or Portuguese—is found in both open and closed syllables in Spanish, as shown in the following table:

| Latin | Spanish | Ladino | Aragonese | Asturian | Galician | Portuguese | Catalan | Occitan | French | Italian | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| petra | piedra | piedra (or pyedra) | piedra | piedra | pedra | pedra | pedra | pedra/pèira | pierre | pietra | piatr? | ‘stone’ |

| terra | tierra | tierra (or tyerra) | tierra | tierra | terra | terra | terra | tèrra | terre | terra | ?ar? | ‘land’ |

| moritur | muere | muere | muere | muerre | morre | morre | mor | morís | meurt | muore | moare | ‘dies (v.)’ |

| mortem | muerte | muerte | muerte | muerte | morte | morte | mort | mòrt | mort | morte | moarte | ‘death’ |

Ladino is the Sephardic equivalent of Yiddish, and I will talk about this language/dialect later.

El español is marked by the palatalization of the Latin double consonants nn and ll (thus Latin annum ? Spanish año, and Latin anellum ? Spanish anillo).

The consonant written ?u? or ?v? in Latin and pronounced [w] in Classical Latin had probably become a bilabial fricative /?/ by the time of Vulgar Latin.

In early español (but not in Catalan or Portuguese) /?/ merged with the consonant written ?b? (a bilabial with plosive and fricative allophones). In modern español, there is no difference between the pronunciation of orthographic ?b? and ?v?.

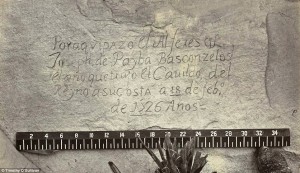

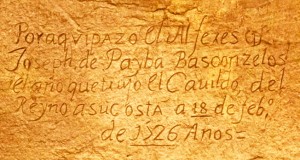

I once photographed a door in Mexico that had many graffiti with misspelled words that were fascinating. The most common misspellings were those which confused b and v and between z and s. ’La bida es sueño.’ ‘Ben conmigo.’ Or, consider this inscription in New Mexico from almost three hundred years ago:

It says, “Por aqui pazó el Alfexes Joseph de Payba Basconzelos el añ0 que tuyo el Cauildo del Reyno a su costa a 18 de feb, de 1726 =

In today’s Spanish, this would be: Por aqui pasó el Alférez José de Payba Basconzelos (Vasconcelos) el año que tuvo el Cauildo del Reino a su costa a 18 de febrero, 1726.

And the English would be something like: By here passed Second Lieutenant Joseph de Payba Vasoncelos, the year that he had the Council of the Kingdom at his cost on 18 February 1726.

An alférez is a second lieutenant, a subaltern, an ensign (in the navy). It’s the first rank that an officer achieves. The Spanish word was derived from the Arabic ?????? (al-f?ris), meaning “horseman” or “knight” or “cavalier”. I remember how proud I was when my father became a second lieutenant.

The initial Latin f- into h- came whenever it was followed by a vowel that did not diphthongize.

The h-, still preserved in spelling, is now silent in most varieties of the language, although in some Andalusian and Caribbean dialects it is still aspirated in some words.

This is the reason why there are modern spelling variants Fernando and Hernando (both Spanish for “Ferdinand”), ferrero and herrero (both Spanish for “smith”), fierro and hierro (both Spanish for “iron”), and fondo and hondo (both Spanish for “deep”, but fondo means “bottom” while hondo means “deep”).

Hacer (Spanish of “to make”) is the root word of satisfacer (Spanish of “to satisfy”), and hecho (“made”) is the root word of satisfecho (Spanish of “satisfied”). In Latin hacer was facere, to do, to make.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, español underwent a dramatic change in the pronunciation of its sibilant consonants known in Spanish as the reajuste de las sibilantes, which resulted in the distinctive velar [x] pronunciation of the letter ?j? and—in a large part of Spain—the characteristic interdental [?] (“th-sound”) for the letter ?z? (and for ?c? before ?e? or ?i?). Thinko thentavos. What cinco centavos sounds like in castellano.

The Gramática de la lengua castellano written in Salamanca in 1492 by Elio Antonio de Nebrija was the first grammar written for a modern European language.

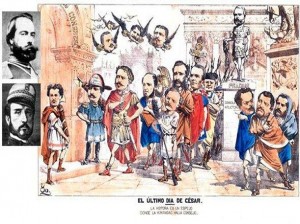

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, author of Don Quixote, is so well known that castellano is often called la lengua de Cervantes.

In the twentieth century, Spanish was introduced to Equatorial Guinea, the Western Sahara and to areas of the United States that had not been part of the Spanish empire, such as Spanish Harlem.

Spanish is an inflected language, with two genders and about fifty conjugated forms per verb. People often choose español in school because they consider it an ‘easy’ language, and only find out later that the verb system is more involved than, say, French or German or Italian. There is actually a preterite subjunctive form that is routinely used in Spanish (Yo quisiera, hubiera) that has long disappeared from French.

The syntax in castellano is often termed right-branching, meaning that subordinate or modifying constituents (such as adjectives) tend to be placed after their head words.

The language uses prepositions (rather than postpositions or inflection of nouns) for case, and usually—though not always—places adjectives after nouns, as do most other Romance languages.

Español is generally a subject verb object language although variations are common, and it allows the deletion of subject pronouns when they are unnecessary because of the verb ending, which is most of the time.

Spanish is a “verb-framed” language, meaning that the direction of motion is expressed in the verb while the mode of locomotion is expressed adverbially (subir corriendo or salir volando). English is ”satellite-framed,” that is, the English equivalents of these examples—’to run up’ and ‘to fly out’ have the mode of locomotion expressed in the verb and the direction in an adverbial modifier).

Subject/verb inversion is not required in questions, and thus the recognition of a declarative or an interrogative phrase may depend entirely on intonation.

The sounds of castellano consist of five vowel phonemes (/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/) and 17 to 19 consonant phonemes (the exact number depending on the dialect).

The main allophonic variation among vowels is the reduction of the high vowels /i/ and /u/ to glides—[j] and [w] respectively—when unstressed and adjacent to another vowel.

Mid vowels /e/ and /o/, determined lexically, alternate with the diphthongs [je]and [we] respectively when stressed, in a process that is better described as morphophonemic rather than phonological.

The consonant phonemes, /?/ and /?/ are often marked with an asterisk (*) to indicate that they are preserved only in some dialects. In most dialects they have been merged, respectively, with /s/ and /?/, in the mergers called, respectively, seseo and yeísmo.

The phoneme /?/ is in often put in parentheses () to indicate that it appears only in words borrowed from another language.

The letters ?v? and ?b? normally represent the same phoneme, /b/, which is realized as [b] after a nasal consonant or a pause, and as [?] elsewhere, as in ambos [?ambos] (‘both’) envío [em?bi.o] (‘I send’), acabar [aka??a?] (‘to finish’) and mover [mo??e?] (‘to move’).

The Royal Spanish Academy considers the /v/ pronunciation for the letter ?v? to be incorrect and even affected.

Some Spanish speakers maintain the pronunciation of the /v/ sound as it is in other western European languages. The sound /v/ is used for the letter ?v? in Spanish by a few second-language speakers in Spain whose native language is Catalan, in the Balneares, around Valencia, and in southern Catalunya.

In the US the pronunciation of the /v/ sound is also common because of the influence of English phonology, and the /v/ is also occasionally used in Mexico. Some parts of Central America also use /v/, which the Royal Academy attributes to the proximity of local indigenous languages.

The /v/ pronunciation was uncommon, but considered correct well into the twentieth century in Spain.

The Spanish rhythm is a syllable-timed language meaning that each syllable has approximately the same duration regardless of stress.

The tuning or intonation of español varies significantly according to dialect, but generally conforms to a pattern of falling tone for declarative sentences and wh-questions (who, what, why, etc.), and rising tone for yes/no questions.

There are no syntactic markers to distinguish between questions and statements, and thus the recognition of declarative or interrogative depends entirely on intonation.

Stress most often occurs on any of the last three syllables of a word, with some rare exceptions at the fourth-last or earlier syllables.

- In words that end with a consonant, stress most often falls on the last syllable, with the following exceptions: The grammatical endings -n (for third-person-plural of verbs) and -s (whether for plural of nouns and adjectives or for second-person-singular of verbs) do not change the location of stress. Thus regular verbs ending with -n and the great majority of words ending with -s are stressed on the penult. Although a significant number of nouns and adjectives ending with -n are also stressed on the penult (e.g. joven, virgen, mitin), the great majority of nouns and adjectives ending with -n are stressed on their last syllable (e.g. capitán, almacén, jardín, corazón).

- Preantepenultimate stress (stress on the fourth-to-last syllable) occurs rarely, and only on verbs with clitic pronouns attached (guardándoselos ’saving them for him/her/them’).

There are numerous minimal pairs which contrast solely on stress such as sábana (‘sheet’) and sabana (‘savannah’), as well as límite (‘boundary’), limite (‘[that] he/she limits’) and limité (‘I limited’), or also líquido (‘liquid’), liquido (‘I sell off’) and liquidó (‘he/she sold off’).

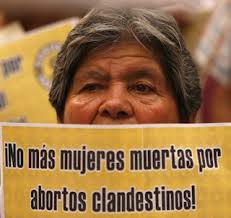

As of 2006, 44.3 million people of the U.S. population were Hispanic by origin, and 38.3 million people, 13 percent, of the population more than five years old speak Spanish at home.

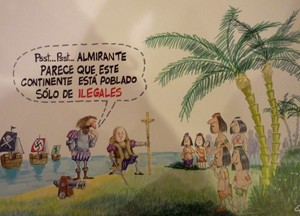

The Spanish language has a long history in the United States due to Spanish and later, Mexican administration over territories in the southwest of the US as well as Florida which was Spanish until 1821.

Spanish is by far the most widely taught second language in the US, and with over 50 million total speakers, the United States is now the second largest Spanish-speaking country in the world after Mexico.

English is, of course the official language of the US, but Spanish is often used in public services and notices at the federal and state levels.

Spanish is used in administration in the state of New Mexico, and has a strong influence in major metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles, Miami, San Antonio, New York, San Francisco, Dallas, Phoenix, and, really, everywhere. Chicago, Las Vegas, Boston, Houston, Baltimore-Washingont, D.C., all due to 20th and 21st century immigration patterns.

Spanish is the official in in Equatorial Guinea, and is the predominant language when native and non-native speakers (around 500,000 people) are counted, while Fang is the most spoken language by number of native speakers there.

In Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony, an unknown number of Sahrawis are able to read and write in Spanish.

The Sawrawi Press Service, official news service of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic of Western Sahara, has been available in Spanish since 2001, and RASD TV, the official television channel of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, has a website available in Spanish.

Western Sahara’s only film festival, The Sahara International Film Festival, is largely funded by Spanish donors and Spanish films are popular.

There is a Spanish literature community among the Sahrawi people, but the Cervantes Institute has denied support and Spanish-language education to Sahrawis in Western Sahara and the Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria.

A group of Sahrawi poets known as Generación de la Amistad saharaui produces Sahrawi literature in Spanish.

The integral territories of Spain in North Africa, which include Ceuta and Melilla, the Plazas de soberanía and the Canary Islands archipelago located just off the northwest coast of mainland Africa have many Spanish speakers.

Morocco is quite close to Spain, of course, and approximately 20,000 people there speak Spanish as a second language, while Arabic is the legal official language and French is widely spoken.

A small number of Moroccan Jews also speak the Sephardic Spanish dialect Haketia (related to the Ladino dialect spoken in Israel).

Spanish is spoken by some communities in Angola because of the Cuban influence from the Cold War and in the south of Sudan among South Sudanese natives that relocated to Cuba during the Sudanese wars and returned in time for their country’s independence.

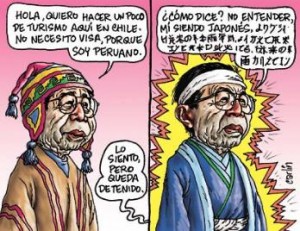

There are important variations— phonological, grammatical and lexical—in the spoken Spanish of the various regions of Spain and throughout the Spanish-speaking areas of the Americas.

The variety of español with the most speakers is Mexican Spanish which is spoken by more than twenty percent of the world’s Spanish speakers. One of its main features is the reduction or loss of unstressed vowels, mainly when they are in contact with the sound /s/.

In Spain, northern dialects are popularly thought of as closer to the standard, although positive attitudes toward southern dialects have increased significantly in the last 50 years.

The speech of Madrid, which has typically southern features such as yeísmo and s-aspiration, is the standard variety for use on radio and television, and is the variety that has most influenced the written standard for Spanish.

The phoneme /?/ (spelled ?z?, or ?c? before ?e? or ?i?)—a voiceless dental fricative as in English thing—is maintained in northern and central Spain, but is merged with the sibilant /s/ in southern Spain, the Canary Islands, and all of Latin-American Spanish. A person from the north of Spain says thielos (cielos ‘heavens’) but in the south of Spain and in South America, they say sielos.

This merger (/?/ to s) is called seseo in Spanish. The phoneme /?/ (spelled ?ll?)—a palatal lateral consonant sometimes compared in sound to the lli of English million—tends to be maintained in less-urbanized areas of northern Spain and in highland areas of South America, but in the speech of most other Spanish-speakers it is merged with /?/ (“curly-tail j“)—a non-lateral, usually voiced, usually fricative, palatal consonant—sometimes compared to English /j/ (yod) as in yacht, and spelled y in Spanish. This merger is called yeísmo in Spanish. And the debuccalization (pronunciation as [h], or loss) of syllable-final /s/ is associated with southern Spain, the Caribbean, and coastal areas of South America.

Almost all speakers of Spanish make the difference between a formal and a familiar second person singular, and so have two different pronouns meaning “you”: usted in the formal, and either tú or vos in the familiar (and each of these three pronouns has its associated verb forms), with the choice of tú or vos varying from one dialect to another.

The use of vos (and/or its verb forms) is called voseo. In a few dialects, all three pronouns are used—usted, tú, and vos—denoting respectively formality, familiarity, and intimacy.

In voseo, vos is the subject form (vos decís, “you say”) and the form for the object of a preposition (voy con vos, “I’m going with you”), while the direct and indirect object forms, and the possessive, are the same as those associated with tú: Vos sabés que tus amigos te respetan. ”Vos te acostaste con el tuerto.” ”Lugar que odio […] como te odio a vos.” ”No cerrés tus ojos.”

The verb forms of general voseo are the same as those used with tú except in the present tense (indicative and imperative) verbs.

The forms for vos generally can be derived from those of vosotros (the traditional second-person familiar plural) by deleting the glide /i?/, or /d/, where it appears in the ending: vosotros pensáis ? vos pensás; vosotros volvéis ? vos volvés, pensad! (vosotros) ? pensá! (vos), volved! (vosotros) ? volvé!

The use of the pronoun vos with the verb forms of tú (e.g. vos piensas) is called “pronominal voseo“. And conversely, the use of the verb forms of vos with the pronoun tú (e.g. tú pensásor tú pensái) is called “verbal voseo“.

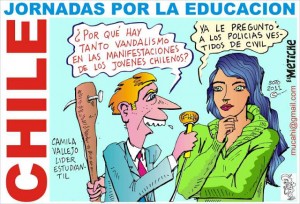

In Chile, for example, verbal voseo is much more common than the actual use of the pronoun vos which is often reserved for deeply informal situations.

Although vos is not used in Spain, it occurs in many Spanish-speaking regions of the Americas as the principal spoken form of the second-person singular familiar pronoun, although with wide differences in social consideration.

It can be said that there are zones of exclusive use of tuteo in the following areas: almost all of Mexico, the West Indies, Panama, most of Peru and Venezuela, coastal Ecuador and the Caribbean coast of Colombia.

Tuteo (the use of tú) as a cultured form alternates with voseo as a popular or rural form in Bolivia, in the north and south of Peru, in Andean Ecuador, in small zones of the Venezuelan Andes (and most notably in the Venezuelan state of Zulia), and in a large part of Colombia. Some researchers claim that voseo can be heard in some parts of eastern Cuba, while others assert that it is absent from the island.

In Chile, tuteo is used as the second-person pronoun with an intermediate degree of formality alongside the more familiar voseo. This is also the case in the Venezuelan state of Zulia, on the Caribbean coast of Colombia(Monteria, Sincelejo, Cartagena, Barranquilla, Riohacha and Valledupar), in the Azuero Peninsula in Panama, in the Mexican state of Chiapas, and in parts of Guatemala.

Areas of generalized voseo include Argentina, Costa Rica, eastern Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Uruguay and the Colombian departments of Antioquia (the second largest in population), Caldas, Risaralda, Quindio, and parts of The Valle del Cauca department.

Ustedes serves as the formal and informal second person plural in over 90% of the Spanish-speaking world, including all of Latin America, the Canary Islands, and some regions of Andalusia.

In Sevilla, Cádiz and other parts of western Andalusia, the familiar form is constructed as ustedes vais, using the traditional second-person plural form of the verb. Most of Spain maintains the formal/familiar division with ustedes and vosotros respectively.

Usted is the usual second-person singular pronoun in a formal context, used to convey respect toward someone who is a generation older or is of higher authority (“you, sir”/”you, ma’am”). It is also used in a familiar context by many speakers in Colombia and Costa Rica, and in parts of Ecuador and Panama, to the exclusion of tú or vos. This usage is sometimes called ustedeo in Spanish.

Once upon a time, when people wanted to be polite, they addressed each other as Vuestra Merced (Your Mercy or Your Grace). In time, Vuestra Merced became usted, and that is why usted takes the singular third person form of the verb. Usted trabaja.

In Central America, especially in Honduras, usted is often used as a formal pronoun to convey respect between the members of a romantic couple. Usted is also used in this way, as well as between parents and children, in the Andean regions of Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela.

The Real Academia Española prefers the pronouns lo and la for direct objects (masculine and feminine respectively, regardless of animacy, meaning “him”, “her”, or “it”), and le for indirect objects (regardless of gender or animacy, meaning “to him”, “to her”, or “to it”). This usage is sometimes called “etymological”, as these direct and indirect object pronouns are a continuation, respectively, of the accusative and dative pronouns of Latin, the mother language of Spanish.

Most speakers adhere to the tradition, and deviations from this norm (more common in Spain than in the Americas) are called leísmo, loísmo or laísmo, according to which respective pronoun—le, lo, or la—has expanded beyond the etymological usage (that is, the use of le as a direct object, or lo or la as an indirect object).

Vocabulary can differ, sometimes radically, in different Spanish speaking countries. Most Spanish speakers can recognize other Spanish forms, even in places where they are not commonly used, but Spaniards generally do not recognize specifically American usages. For example, Spanish mantequilla, aguacate and albaricoque (respectively, ‘butter’, ‘avocado’, ‘apricot’) correspond to manteca, palta, and damasco, respectively, in Argentina, Chile (except manteca), Paraguay, Peru (except manteca and damasco), and Uruguay.

The words coger (‘to take’), pisar (‘to step on’) and concha (‘seashell’) are considered extremely rude in parts of Latin America, where the meaning of coger and pisar is also “to have sex” and concha means “vulva”.

The Puerto Rican word for “bobby pin” (pinche) is an obscenity in Mexico, but in Nicaragua it simply means “stingy”, and in Spain refers to a chef’s helper.

The last big earthquake in Mexico was on a Thursday, and there was a joke about Plácido Domingo who happened to be in the country at that time. Plácido Domingo means ‘calm Sunday’ and the joke was that after the quake he had changed his name to Pinche Jueves (‘Fuck Thursday’).

Taco means “swearword” (among other things) in Spain, “traffic jam” in Chile and “heels” (shoe) in Argentina and Peru, but is known to the rest of the world as a Mexican dish.

Pija in many countries of Latin America and Spain itself is a slang word for “penis”, while in Spain the word also signifies “posh girl” or “snobby”.

Coche, which means “car” in Spain, central Mexico and Argentina, for the vast majority of Spanish-speakers actually means “baby-stroller” or “pushchair”, while carro means “car” in some Latin American countries and “cart” in others, as well as in Spain.

Papaya is the slang term for “vagina” in parts of Cuba and Venezuela, where the fruit is instead called fruta bomba and lechosa, respectively.

In Argentina, one says “piña” when talking about ‘punching’ someone, whereas in other countries, “piña” refers to a pineapple.

Although Portuguese and Spanish are very closely related, particularly in vocabulary (89% lexically similar according to the Ethnologue of Languages), syntax and grammar, there are some differences that don’t exist between Catalan and Portuguese.

Spanish and Portuguese are widely considered to be mutually intelligible. However most Portuguese speakers can understand spoken Spanish with little difficulty, but Spanish speakers face more difficulty in understanding spoken Portuguese. The written forms are considered to be mutually intelligible.

Ladino, also known as Judaeo-Spanish, is essentially medieval Spanish and closer to modern Spanish than any other language, is spoken by many descendants of the Sephardim who were driven out of Spain in the fifteenth century.

Ladino is to Spanish as Yiddish is to German.

Ladino speakers are currently almost exclusively Sephardic Jews, with family roots in Turkey, Greece or the Balkans. Most Ladino speakers now live in Israel and Turkey, and the United States, with a few pockets in Latin America.

Ladino lacks many of the words that came into Spanish from the Americas during the colonial period, and it retains many archaic features which have since been lost in standard Spanish. It contains, however, other vocabulary which is not found in standard Spanish, including vocabulary from Hebrew, French, Greek and Turkish, and other languages spoken where the Sephardim settled.

Judaeo-Spanish is in danger of extinction because many native speakers today are elderly olim (immigrants to Israel) who have not transmitted the language to their children or grandchildren. However, Ladino is experiencing a minor revival among Sephardic communities, especially in music. In the case of the Latin American communities, the danger of extinction is also due to the risk of assimilation by modern Castilian.

Haketia, the Judaeo-Spanish of northern Morocco is related to Ladino. This language also tended to assimilate with modern Spanish, during the Spanish occupation of the region.

Ladino is also known as Judezmo, Dzhudezmo, or Spaniolit. In Amsterdam, England and Italy, those Jews who continued to speak ‘Ladino’ were in constant contact with Spain and therefore they basically continued to speak the Castilian Spanish of the time.

In the Sephardic communities of the Ottoman Empire, however, Ladino not only retained the older forms of Spanish, but borrowed so many words from Hebrew, Arabic, Greek, Turkish, and even French, that it became more and more distant from standard Spanish. Ladino was nowhere near as diverse as the various forms of Yiddish, but there were still two different dialects, which corresponded to the different origins of the speakers.

‘Oriental’ Ladino was spoken in Turkey and Rhodes and reflected Castilian Spanish, whereas ‘Western’ Ladino was spoken in Greece, Macedonia, Bosnia, Serbia and Romania, and preserved the characteristics of northern Spanish and Portuguese.

The vocabulary of Ladino includes hundreds of archaic Spanish words which have disappeared from modern day Spanish, and also includes many words from different languages that have been substituted for the original Spanish word, from the various places Ladino speaking Jews settled.

These foreign words derive mainly from Hebrew, Arabic, Turkish, Greek, French, and to a lesser extent from Portuguese and Italian.

Ladino was written in the Hebrew alphabet, in Rashi script, or in Solitro, a cursive method of writting letters.

It was only in the 20th century that Ladino was written using the Latin alphabet.

What is known as ‘rashi script’ was originally a Ladino script which became used centuries after Rashi’s death in printed books to differentiate Rashi’s commentary from the text of the Torah.

Ladino has been spoken in North Africa, Egypt, Greece, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, France, Israel, and, to a lesser extent, in the United States (the highest populations being in Seattle, Los Angeles, New York, and south Florida) and Latin America.

By the beginning of this century, with the spread of compulsory education in the language of the land, Ladino began to disintegrate. Emigration to Israel from the Balkans hastened the decline of Ladino in Eastern Europe and Turkey.

Israel is now the country with the greatest number of Ladino speakers, with about 200,000 people who still speak or understand the language, but even they only know a very limited and basic Ladino.

Here is an example of Ladino. Can you read it? Rika nasio en Estanbol, serka de la Kula de Galata, una parte de la sivdad ande biviyan los desandantes de akeyos espanyoles djudios a ken un sultan jeneroso aviya dado refujio debasho del kresiente turko, avriendoles las puertas i los brasos, kon las palavras historikas: “Los ke los mandan piedren, i yo gano”

This is what it would be in Spanish: Rika nació en Istanbul, cerca de la Kula de Galata, una parte de la ciudad donde vivían los descendientes de aquellos españoles judíos a quien un sultan generoso había dado refúgio debajo del crescente turco, abriéndoles las puertas y los brazos, con las palabras históricas: “Los que los preguntan ayuda, y yo gano.”

Rika was born in Istanbul, near the Kula of Galata, a part of the city where the descendants of those Spanish Jews lived, to whom a generous sultan had given refuge under the Turkish crescent, opening to them their doors and arms, with the historic words: ”Those that ask help, help them and we win.”

Su nombre era Ester, komo la reyna, i su tipo korrespondiya al ke descrive la Biblia: Brunika kon ojos pretos i kaveyos frizados. En el serklo familiar, la yamavan Esterika, i finalmente Rika.

Su nombre era Ester, como la reina, y su tipo correspondía al que describe la Biblía: Morena con ojos prietos y cabellos frisados. En el cerclo familiar, la llamában Esterika, y finalmente Rika.

Many of these spellings in Ladino look like the misspellings I saw so long ago on that bathroom door in Mexico. And they look like spellings that people use on iPhones and Facebook today, especially the k for que.

At least to judge by those examples above, Ladino is really Spanish and very little Hebrew, just as Yiddish is really German and very little Hebrew. I know almost no Hebrew and yet can read Yiddish and Ladino if they are written in a Roman alphabet.

Upon leaving Spain, whole communities of Jews headed east through Italy to the lands of the Ottoman Empire at the invitation of Sultan Bayazid.

Important centers for Ladino speakers, which survived until the Second World War, grew in present-day Turkey, Greece, Israel, and Egypt, with smaller ones in Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, and the island of Rhodes. Their speech is described by linguists as eastern Judaeo Spanish.

For a century or so prior to the Expulsion, persecuted Spanish Jews also found shelter in North Africa, and speech communities grew along the northern coast of Morocco.

The speech of this region, which bears a marked resemblance to its eastern counterpart both phonetically and in the retention of Old Spanish lexemes, is denominated western.

Spanyol is perhaps the most commonly used name for their language among speakers of Ladino, with its unmistakable reference to their linguistic and cultural origins.

The widespread use of the term Spanyol is confirmed by the Modern Hebrew coinage Spanyolit (Spanyol + Heb. suffix for forming language names), the name by which the language was referred to until quite recently in Israel.

Ladino, probably the earliest attested name, has the widest currency today, and certainly so in Israel where the largest speech-communities in the modern world are to be found.

The names Judezmo and Judió/Jidió, which are registered in some 19th- and early 20th-century communal publications, clearly have the function of underlining a Jewish identification among speakers.

Judezmo is the Spanish word for “Judaism”, and, for this reason, is used by certain scholars today who wish, on ideological grounds, to draw a semantic equation between Judezmo and Yiddish.

It seems rather late in the day to rename the language. Faced by this terminological plurality, scholarship has generally opted for the more descriptive and neutral “Judeo-Spanish.”

In the western Mediterranean, the language is frequently referred to as hakitia or Haketia (formed on Moroccan Arabic haka “to converse” + diminutive suffix), although it is interesting to note that with the renewed impact of Modern Spanish in this area in the 19th century, the term is reserved by speakers to describe an artificial language of humor which abounds in archaic forms of Spanish and Hispanicized Arabisms, or else to the language as spoken in some distant past.

Athough it is more similar to Modern Spanish than its eastern counterpart, Haketia continues to preserve many characteristic features of Judeo Spanish.

Up to the beginning of the 20th century the language was almost always written in Hebrew characters using the standard Hebrew alphabet with some modifications, mostly in the form of diacritical marks, to accommodate Hispanic phonemes.

The earliest texts appeared in “square” characters either with or without vowels, but the bulk of printed material is in a cursive (rabbinic) script. Some early manuscripts preserve a cursive script known as solitreo, which is still in use among native speakers in personal correspondence.

The best-known and most widely translated Judeo Spanish work of the post exilic period is the Me’am Lo’ez (1730), which was begun by Yaacov Khuli and continued over a long period, in series form, by a number of different authors writing under the same name.

A midrashic work, the Me’am Lo’ez is structured mainly on the Pentateuch and spans the sources of Jewish thought.

The beginning of the 19th century saw the growth of a secular literature, which was popular, for the most part, and included a sizable corpus of original compositions such as novels, short stories, plays, and popular histories as well as adaptations of major European novels of the period, where the impact of French on Judeo Spanish is significantly felt.

This growth of secular literature is also observed in the Judeo Spanish press which began to flourish in the eastern Mediterranean at the same time.

Only a small number of Judeo Spanish newspapers continues to appear today.

Spanyol, Ladino, Judeo Spanish, whatever y0u want to call the language, it is quickly disappearing, despite much interest in it.

This is the sort of paradox we see in the Celtic languages of Brittany, Cornwall, Ireland and Wales. Now that they are almost gone, people begin to realize what is being lost and there is a fierce, patriotic interest in them.

See you next week?

Sam Andrew Jack Casady

__________________________________________

![libros_calleja[1]](https://samandrew.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/libros_calleja1-300x159.jpg)