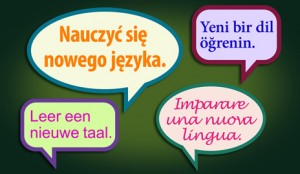

The native name for Polish is polski (Polish), język polski (the Polish language), or more formally, polszczyzna (Polish).

Napisz do mnie.

Literary Polish is based on the dialects of Gniezno, Cracow and Warsaw, though there is some dispute about this.

Lubię podróżować.

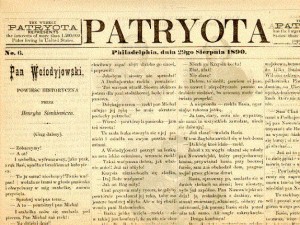

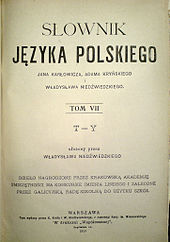

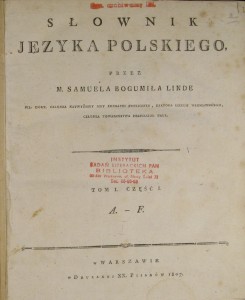

Polish first appeared in writing in 1136 in the “Gniezno papal bull” (Bulla gnieźnieńska), which included 410 Polish names.

Zaczekaj chwilkę…

The first written Polish sentence was day ut ia pobrusa a ti poziwai (I’ll grind [the corn] in the quern and you’ll rest), which appeared in Ksiega henrykowska in 1270.

In Modern Polish spelling that sentence is daj ać ja pobruszę, a ty poczywaj.

Daj mi więcej szczegółów.

Polish is a Western Slavonic language with about 50 million speakers mainly in Poland.

Poważnie.

There are also significant Polish communities in Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine, and significant numbers of Polish speakers in many other countries, including the Czech Republic, Germany, Slovakia, Latvia, Romania, the UK and USA.

Rozumiesz?

Polish is closely related to Kashubian, Lower Sorbian, Upper Sorbian, Czech and Slovak.

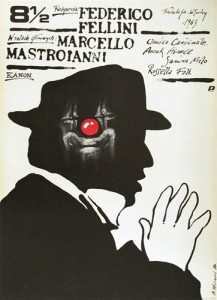

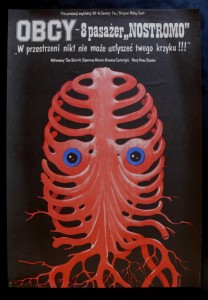

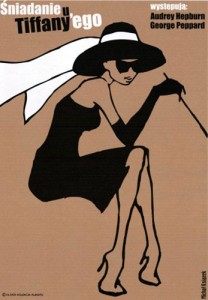

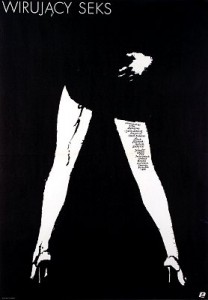

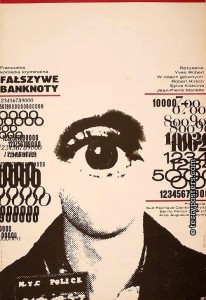

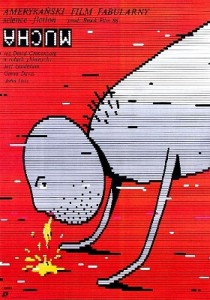

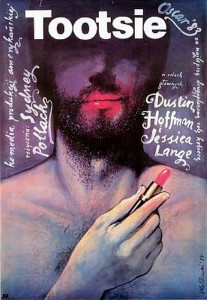

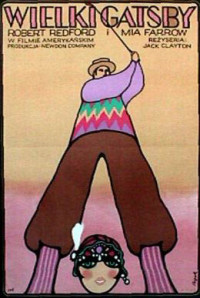

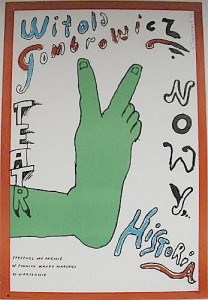

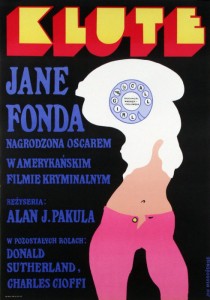

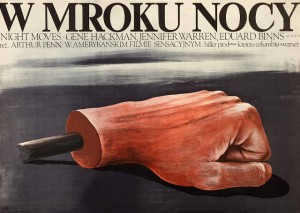

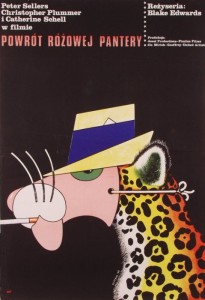

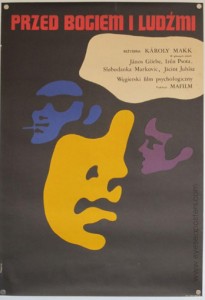

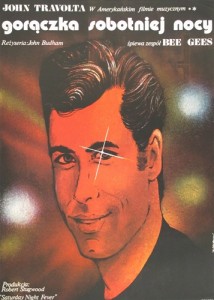

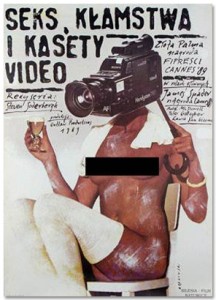

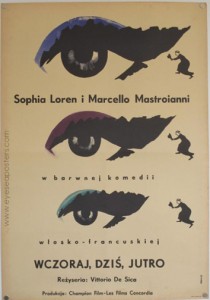

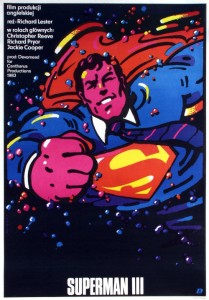

This poster is supposed to say Bad Teacher, but it doesn’t.

The Polish alphabet derives from Roman letters (the alphabet we use), but includes certain additional letters formed using diacritical accents.

Jaki masz zawód?

The Polish alphabet was one of three major forms of Latin-based orthography developed for Slavic languages, the others being the Czech and Croatian alphabets.

Kashubian uses a Polish-based system, Slovak uses a Czech-based system, and Slovene follows the Croatian one.

The Sorbian languages blend the Polish and the Czech alphabets.

Skąd jesteś?

The diacritical marks used in the Polish alphabet are the kreska (graphically similar to the acute accent) in the letters ć, ń, ó, ś, ź and through the letter in ł.

The kropka (superior dot) in the letter ż, and the ogonek (“little tail”) in the letters ą, ę.

Jestem zajęty.

The letters q, v, x are often not considered part of the Polish alphabet.

They are used only in foreign words and names.

Nie pamiętam.

Polish orthography is largely phonemic, meaning that there is a close correspondence between the way that the language is written and the way that it is spoken. Spanish is also largely phonemic. English is not.

Nie wierzę w to.

In Polish there is a consistent correspondence between letters (or digraphs and trigraphs) and phonemes.

| Upper case |

Lower case |

Phonemic value(s) |

Upper case |

Lower case |

Phonemic value(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | /a/ | M | m | /m/ |

| Ą | ą | /ɔ̃/, /ɔn/, /ɔm/ | N | n | /n/ |

| B | b | /b/ (/p/) | Ń | ń | /ɲ/ |

| C | c | /ts/ | O | o | /ɔ/ |

| Ć | ć | /tɕ/ | Ó | ó | /u/ |

| D | d | /d/ (/t/) | P | p | /p/ |

| E | e | /ɛ/ | R | r | /r/ |

| Ę | ę | /ɛ̃/, /ɛn/, /ɛm/, /ɛ/ | S | s | /s/ |

| F | f | /f/ | Ś | ś | /ɕ/ |

| G | g | /ɡ/ (/k/) | T | t | /t/ |

| H | h | /x/ | U | u | /u/ |

| I | i | /i/, /j/ | W | w | /v/ (/f/) |

| J | j | /j/ | Y | y | /ɨ/ |

| K | k | /k/ | Z | z | /z/ (/s/) |

| L | l | /l/ | Ź | ź | /ʑ/ (/ɕ/) |

| Ł | ł | /w/ | Ż | ż | /ʐ/ (/ʂ/) |

The following digraphs and trigraphs are used:

| Digraph | Phonemic value(s) | Digraph/trigraph (before a vowel) |

Phonemic value(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ch | /x/ | ci | /tɕ/ |

| cz | /tʂ/ | dzi | /dʑ/ |

| dz | /dz/ (/ts/) | gi | /ɡʲ/ |

| dź | /dʑ/ (/tɕ/) | (c)hi | /xʲ/ |

| dż | /dʐ/ (/tʂ/) | ki | /kʲ/ |

| rz | /ʐ/ (/ʂ/) | ni | /ɲ/ |

| sz | /ʂ/ | si | /ɕ/ |

| zi | /ʑ/ |

Voiced consonant letters frequently come to represent voiceless sounds.

This occurs at the end of words and in certain clusters.

Occasionally also voiceless consonant letters can represent voiced sounds in clusters.

Jesteś tak piękna.

The spelling rule for the palatal sounds /ɕ/, /ʑ/, /tɕ/, /dʑ/ and /ɲ/ is as follows: before the vowel i the plain letters s, z, c, dz, n are used.

Before other vowels the combinations si, zi, ci, dzi, ni are used.

When not followed by a vowel the diacritic forms ś, ź, ć, dź, ń are used.

For example, the s in siwy (pronounced /śiwy/—”grey-haired”), the si in siarka (pronounced /śarka/—”sulphur”) and the ś in święty (pronounced /święty/—”holy”) all represent the sound /ɕ/.

The exceptions to the above rule are certain loanwords from Latin, Italian, French, Russian or English—where s before i is pronounced as s, e.g. sinus, sinologia, do re mi fa sol la si do, Saint-Simon i saint-simoniści, Sierioża, Siergiej, Singapur, singiel. In other loanwords the vowel i is changed to y, e.g. Syria, Sybir, synchronizacja, Syrakuzy.

Jestem głodny.

| Phonemic value | Single letter/Digraph (in pausa or before a consonant) |

Digraph/Trigraph (before a vowel) |

Single letter/Digraph (before the vowel i) |

|---|---|---|---|

| /tɕ/ | ć | ci | c |

| /dʑ/ | dź | dzi | dz |

| /ɕ/ | ś | si | s |

| /ʑ/ | ź | zi | z |

| /ɲ/ | ń | ni | n |

Similar principles apply to /kʲ/, /ɡʲ/, /xʲ/ and /lʲ/, except that these can only occur before vowels, so the spellings are k, g, (c)h, l before i, and ki, gi, (c)hi, li otherwise.

Most Polish speakers, however, do not consider palatalisation of k, g, (c)h or l as creating new sounds.

Except in the cases mentioned above, the letter i if followed by another vowel in the same word usually represents /j/, yet a palatalisation of the previous consonant is always assumed.

Niech pomyślę…

The letters ą and ę, when followed by plosives and affricates, represent an oral vowel followed by a nasal consonant, rather than a nasal vowel.

For example, ą in dąb (“oak”) is pronounced /ɔm/, and ę in tęcza (“rainbow”) is pronounced /ɛn/ (the nasal assimilates with the following consonant).

When followed by l or ł (for example przyjęli, przyjęły), ę is pronounced as just e. When ę is at the end of the word it is often pronounced as just /ɛ/.

Note that, depending on the word, the phoneme /x/ can be spelled h or ch.

Proszę.

The phoneme /ʐ/ can be spelled ż or rz.

And /u/ can be spelled u or ó.

In several cases such spelling changes can determine the meaning, for example: może (“maybe”) and morze (“sea”).

In occasional words, letters that normally form a digraph are pronounced separately.

For example, rz represents /rz/, not /ʐ/, in words like zamarzać (“freeze”) and in the name Tarzan.

Notice that doubled letters represent separate occurrences of the sound in question; for example Anna is pronounced /anna/ in Polish (the double n is often pronounced as a lengthened single n).

There are certain clusters where a written consonant would not be pronounced.

For example, the ł in the words mógł (“could”) and jabłko (“apple”) might be omitted in ordinary speech, leading to the pronunciations muk and japko or jabko.

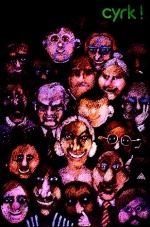

A name for this might be Ponglish.

Polish is a highly inflected language, with relatively free word order, although the dominant arrangement is subject verb object (SVO).

There are no articles, and subject pronouns are usually dropped as is often the case with inflected languages.

Nouns can be masculine, feminine or neuter.

A distinction is also made between animate and inanimate masculine nouns in the singular, and between masculine personal and non-personal nouns in the plural.

Porozmawiajmy.

There are seven cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, instrumental, locative and vocative.

A word can change in Polish depending on how it is used. We have this phenomenon in English, but you may not have noticed it since English is your native language.

We have cases, but they are mostly in the pronouns.

I is in the nominative case. My is genitive, me is accusative and dative.

In Latin, the language where I originally encountered the idea of cases, I is ego. This is the nominative case.

The gentive case for the first person pronoun in Latin is meus, mea, meum.

The Latin accusative case for ego is me.

To say to me, the dative case of the first personal pronoun in Latin, one says mihi.

In German, the cases for I are ich (nominative), mein (genitive), mich (accusative) and mir (dative).

The declension of nouns in Polish has become simpler.

Now it depends on the gender of a noun (smok, o smoku – foka, o foce) (a dragon, about a dragon – a seal, about a seal) and to some extend on the hardness of a noun’s stem (liść, liście – list, listy)(leaf – leaves, letter – letters).

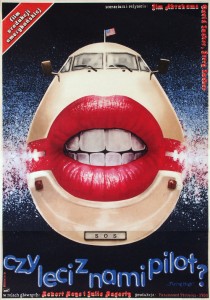

Two categories have appeared in the masculine gender: the category of animacy and of personhood (but, widzę but, widzę buty – kot, widzę kota, widzę koty – pilot, widzę pilota, widzę pilotów) (a shoe, I see a shoe, I see shoes – a cat, I see a cat, I see cats – a pilot, I see a pilot, I see pilots).

Traces of consonant stems still remain but almost exclusively in neuter noun stems ending in -en, -ent- (cielę – cielęcia, imię – imienia) (a calf – of a calf, a name – of a name).

For all other stems, long or short form has become characteristic of all cases.

In general, in the past endings characteristic of stems ending in -o-, -jo- and -a-, -ja- were most common.

Other word endings were disappearing.

The endings which did not cause the alteration of the stem were becoming more popular.

Traces of the lack of softness in some forms of words softened by front vowels (mainly forms ending with a consonant or ending with -i-, egz. krъvaxъ > *krwach > krwiach) have disappeared.

Often softness is the only remnant of old noun endings (Gen. kamane > kamienia) (of stone).

Powodzenia.

Declension of nouns (cases) is becoming simpler in many, most languages, not just in Polish.

It’s a natural progression.

As they evolve, languages become simpler.

It is the ‘primitive’ languages that are most complicated. Old, old languages, like Chinese, are quite simple. No gender, no number, no conjugations, certainly no cases. Very streamlined.

In English we have lost almost all of the cases.

Whom (accusative, dative) is going to disappear any day now.

Whom did you see there? is beginning to sound stilted and artificial, a sure sign of a moribund grammatical form.

Przepraszam, jestem za późno.

Adjectives in Polish agree with nouns in terms of gender, case and number.

Attributive adjectives most commonly precede the noun, although in certain cases, especially in fixed phrases (like język polski, “Polish (language)”), the noun may come first.

Most short adjectives and their derived adverbs form comparatives and superlatives by inflection (the superlative is formed by prefixing naj- to the comparative).

Verbs are of imperfective or perfective aspect, often occurring in pairs.

Imperfective verbs have a present tense, past tense, compound future tense except for być “to be”, which has a simple future będę, this in turn being used to form the compound future of other verbs.

Imperfective verbs also have a subjunctive/conditional (formed with the detachable particle by), imperatives, an infinitive, present participle, present gerund and past participle.

Perfective verbs have a simple future tense (formed like the present tense of imperfective verbs), past tense, subjunctive/conditional, imperatives, infinitive, present gerund and past participle.

Conjugated verb forms agree with their subject in terms of person, number, and (in the case of past tense and subjunctive/conditional forms) gender.

Passive constructions can be made using the auxiliary być or zostać (“become”) with the passive participle.

There is also an impersonal construction where the active verb is used (in third person singular) with no subject, but with the reflexive pronoun się present to indicate a general, unspecified subject as in pije się wódkę “vodka is drunk.”

Note that wódka appears in the accusative.

A similar sentence type in the past tense uses the passive participle with the ending -o, as in widziano ludzi (“people were seen”).

As in other Slavic languages, there are also subjectless sentences formed using such words as można (“it is possible”) together with an infinitive.

Nie znam jej.

Yes – No questions, both direct and indirect, are formed by placing the word czy at the beginning.

Negation uses the word nie, before the verb or other item being negated; nie is still added before the verb even if the sentence also contains other negatives such as nigdy (“never”) or nic (“nothing”).

In Polish, as in many languages, double negatives are standard.

Cardinal numbers have a complex system of inflection and agreement.

Numbers higher than five (except for those ending with the digit 2, 3 or 4) govern the genitive case rather than the nominative or accusative.

Special forms of numbers (collective numerals) are used with certain classes of noun, which include dziecko (“child”) and exclusively plural nouns such as drzwi (“door”).

Ile to kosztuje?

Polish has, over the centuries, borrowed a number of words from other languages.

Usually, borrowed words have been adapted rapidly in the following ways:

- Spelling was altered to approximate the pronunciation, but written according to Polish phonetics.

Two: Word endings are liberally applied to almost any word to produce verbs, nouns, adjectives, as well as adding the appropriate endings for cases of nouns, diminutives, augmentatives or whatever ending is needed.

Depending on the historical period, borrowing has proceeded from various languages.

Recent borrowing is primarily of international words from English, mainly those that have Latin or Greek roots.

Komputer (computer), korupcja (corruption) and many other examples.

Slang sometimes borrows and alters common English words, e.g. luknąć (to look).

Concatenation of parts of words (auto-moto), which is not native to Polish but common in English is also sometimes used.

When borrowing international words, Polish often changes their spelling.

Zadzwonię jeszcze.

The Latin suffix ‘-tion’ corresponds to -cja. To make the word plural, -cja becomes -cje.

Examples of this include inauguracja (inauguration), dewastacja (devastation), recepcja (reception), konurbacja (conurbation) and konotacje (connotations).

The digraph qu becomes kw (kwadrant = quadrant; kworum = quorum).

Other notable influences in the past have been Latin (9th–18th centuries), Czech (10th and 14th–15th centuries), Italian (15th–16th centuries), French (18th–19th centuries), German (13–15th and 18th–20th centuries), Hungarian (14th–16th centuries) and Turkish (17th century).

The Latin language, for a very long time the only official language of the Polish state, has had a great influence on Polish.

Many Polish words (rzeczpospolita from res publica, zdanie for both “opinion” and “sentence”, from sententia) were direct calques from Latin.

Many words have been borrowed from the German language, as a result of Poland and Germany being neighbors for a millennium, and also as the result of a sizable German population in Polish cities during medieval times.

German words found in the Polish language are often connected with trade, the building industry, civic rights and city life.

Some German words were wholly assimilated into Polish.

Handel (trade) and dach (roof)

Other borrowings from German are pronounced the same, but differ in writing schnur—sznur (cord).

The Polish language has many German expressions which have become literally translated (calques).

The regional dialects of Upper Silesia and Masuria (Modern Polish East Prussia) have noticeably more German loanwords than other dialects.

Latin was known to a larger or smaller degree by most of the numerous szlachta in the 16th to 18th centuries (and it continued to be extensively taught at secondary schools until World War II).

Apart from dozens of loanwords, the influence of Latin can also be seen in the somewhat greater number of verbatim Latin phrases in Polish literature (especially from the 19th century and earlier), than, say, in English.

In the 18th century, with the rising prominence of France in Europe, French supplanted Latin in this respect.

Some French borrowings also date from the Napoleonic era, when the Poles were enthusiastic supporters of Napoleon.

Examples include ekran (from French écran, screen), abażur (abat-jour, lamp shade), rekin (requin, shark), meble (meuble, furniture), bagaż (bagage, luggage), walizka (valise, suitcase), fotel (fauteuil, armchair), plaża (plage, beach) and koszmar (cauchemar, nightmare).

Some place names have also been adapted from French, such as the Warsaw borough of Żoliborz (joli bord=beautiful riverside), as well as the town of Żyrardów (from the name Gérard, with the Polish suffix -ów attached to refer to the owner/founder of a town).

Other words are borrowed from other Slavic languages, for example, sejm, hańba and brama from Czech.

There are many, many borrowings from Yiddish. Words like bachor (an unruly boy or child), bajzel (slang for mess), belfer (slang for teacher), ciuchy (slang for clothing), cymes (slang for very tasty food), geszeft (slang for business), kitel (slang for apron), machlojka (slang for scam), mamona (money), menele (slang for oddments and also for homeless people), myszygine (slang for lunatic), pinda (slang for girl, pejorative), plajta (slang for bankruptcy), rejwach (noise), szmal (slang for money), and trefny (dodgy).

Typical loanwords from Italian include pomidor from pomodoro (tomato), kalafior from cavolfiore (cauliflower), pomarańcza from pomo and arancio (orange).

Those Italian loan words were introduced in the times of Queen Bona Sforza (the wife of Polish King Sigismund the Old), who was famous for introducing Italian cuisine to Poland, especially vegetables.

Another word of Italian origin is autostrada (from Italian “autostrada”, highway).

The contacts with Ottoman Turkey in the 17th century brought many new words, some of them still in use, such as: jar (deep valley), szaszłyk (shish kebab), filiżanka (cup), arbuz (watermelon), dywan (carpet).

The mountain dialects of the Górale in southern Poland, have quite a number of words borrowed from Hungarian (baca, gazda, juhas, hejnał).

There are also loanwords from Romanian as a result of historical contacts with Hungarian-dominated Slovakia and Wallachian herders who travelled north along the Carpathians.

The cant and slang of thieves include such words as kimać (to sleep) or majcher (knife) of Greek origin, considered then unknown to the outside world.

Direct borrowings from Russian are extremely rare, in spite of long periods of dependence on Czarist Russia and the Soviet Union, and are limited to a few international words, such as sputnik and pierestroika.

Russian personal names are transcribed into Polish likewise.

Tchaikovsky’s name is spelled Piotr Iljicz Czajkowski.

There are also a few words borrowed from the Mongolian language, e.g. dzida (spear) or szereg (a line or row).

These words were brought to the Polish language during wars with the armies of Gengis Khan and his descendants.

Do widzenia, do zobaczenia.

The differences between Polish and Slovak are roughly comparable to the differences between the German and Swiss German dialects (75% of the vocabulary similar or the same).

Polish and Russian have approximately the same relationship as Spanish and Italian (55-60% of the vocabulary the same or similar).

The difference between Polish and Bulgarian is about the same as that between English and Dutch (40% of the vocabulary the same or similar).

The most similar to Slavic languages are the Baltic Languages: Latvian and Lithuanian, but only 3% of the vocabulary is alike.

The Polish language belongs to the West-Slavic group of the Indo-European languages together with Czech and Slovak.

Polish emerged from the Proto-Slavic language, the mother tongue of all Slavic tribes in the past.

Polish has evolved to such a degree that the texts written in the Middle Ages are not 100-per-cent understandable to contemporary Poles and need to be read with a dictionary of archaisms.

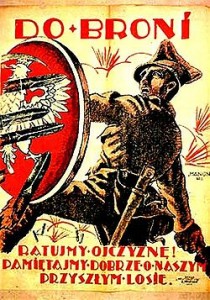

During the Partitions of Poland (1795-1918) the Prussian and Russian conquerors tried to eradicate Polish identity, but their plans eventually failed and Poles retained their language almost intact.

Polish is used as a second language in some parts of Russia, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

This dispersal has been caused by many migrations and resettlements as well as frontier changes brought by the Yalta agreement in 1945 after World War II.

As a result, many Poles were left outside the territory of their fatherland.

Pieniądze

Poland is the most linguistically homogeneous European country.

Nearly 97% of Poland’s citizens declare Polish as their mother tongue.

Ethnic Poles constitute large minorities in Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine.

Polish is the most widely used minority language in Lithuania’s Vilnius County (26% of the population, according to the 2001 census results, with Vilnius having been part of Poland until 1939) and is found elsewhere in southeastern Lithuania.

In Ukraine it is most common in the western Lviv and Volyn oblast (provinces), while in western Belarus it is used by the significant Polish minority, especially in the Brest and Grodno regions and in areas along the Lithuanian border.

Polish is spoken, naturally, by Polish emigrants living all around the world, also by their children and grandchildren. The total number of speakers worldwide is about 50 million.

Moje slońce. My sun.

Mój kwiatuszku. My flower.

Do następnego razu… Till next time…

Sam Andrew

____________________________________________________