The age of the Baroque (1600-1750) was the Roman Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation which had happened in the century before.

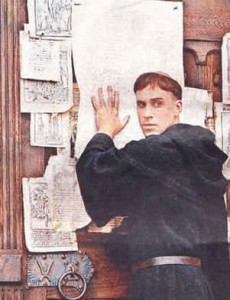

The Reformation was a hard, biting, burning, purifying time of extreme measures, necessary, salutary in some aspects, but very difficult to live through.

The Reformationists burned books and monasteries and smashed statues and other “idolatrous” objects, scraping all of the art, ornamentation, fun and frivolity out of their religion.

In response to this dour, severe, doctrinal era, the Church embarked on a program of restoration, a new way of living that became known as the Counter Reformation.

The purpose of the Counter Reformation was aimed at remedying some of the abuses challenged by the Protestants earlier in the 16th century.

The Baroque which grew out of the Counter Reformation was an age of exaggerated motion and clear, easily interpreted detail to produce drama, tension, exuberance, and grandeur in sculpture, painting, architecture, literature, dance and music.

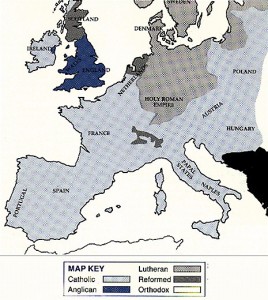

The style began around 1600 in Rome and spread to most of Europe.

Concilium Tridentinum, the Council of Trent, who met in Trento, Italy, between December 13, 1545, and December 4, 1563 in twenty-five sessions for three periods. was an embodiment of the ideals of the Counter Reformation and was considered to be one of the Church’s most important councils.

Trento was then the capital of the Prince Bishopric of Trent of the Holy Roman Empire.

The popularity and success of the Baroque style was initiated by the Catholic Church which had decided at the Council of Trent, in response to the arid, purifying doctines of the Reformation, that the arts should communicate religious themes in direct and emotional involvement straight into the hearts of the common people.

The aristocracy cooperated with this goal because they saw the dramatic style of Baroque architecture and art as a means of impressing visitors and expressing triumphant power and control. Tiziano (Titian) did this portrait of Pope Paul III (Paulus PP III), who was born Alessandro Farnese.

Baroque palaces are built around an entrance of courts, grand staircases and reception rooms of increasing opulence.

The term baroque, by the way, comes from the Portuguese word barroco, meaning misshapen pearl. These misshapen pearls are beautifully dramatic in their irregularity.

These are still called baroque pearls today. The era is named for the pearl and not the other way round.

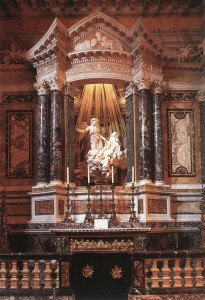

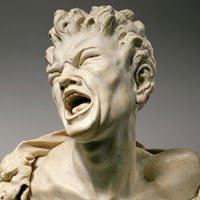

In the Baroque period, the Roman Church realized the power that art could have to inspire and, therefore, she became preoccupied with extravagance and display. There was a stagey, theatrical quality to the works in the Baroque which were often highly emotional and done in mixed media. Much Baroque sculpture added extra-sculptural elements, concealed lighting, or water fountains, or fused sculpture and architecture to create a transformative experience for the viewer.

The intent was to overwhelm viewers, catch their attention, and make them want to see more. This is Ludovica by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, one of the greatest sculptors of all time, whose talents were perfectly suited to the Baroque.

Entering a Baroque church where visual space, music and ceremony were combined inspired the loyalty of congregations.

The bigger and more beautiful the space, the more people wanted to enter it.

Complex geometry, curving and intricate stairway arrangements and large-scale sculptural ornamentation offered a sense of movement and mystery within the Baroque palace of worship.

It was the reverence for the church that provided funding for more and more building projects which, in turn, brought even more worshipers into the city –as many as five times the permanent population during a Holy Year.

With this boom in tourism, a continuing job opportunity arose for the citizens of Rome.

The construction industry soon became the largest employer in the city.

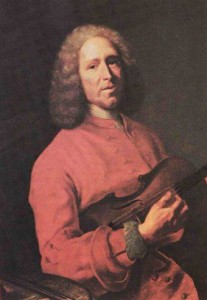

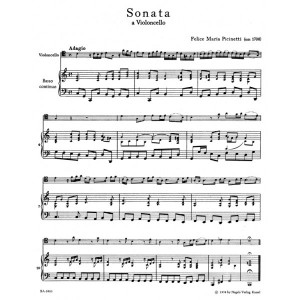

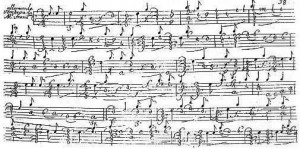

Music filled these churches. The term “baroque” was, in fact, first applied to music. It was a perjorative term at first, as most labels are. An anonymous writer in the Mercure de France (May 1734) noted that the opera of Jean-Philippe Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie, was “du barocque,” was endless dissonance, constantly changing in key and meter, and was a pastiche of every compositional device. You know? What people always say about new music.

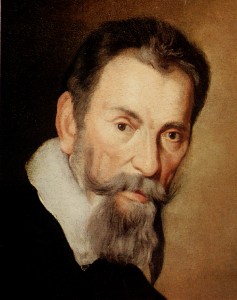

One hundred and fifty years, from 1600 to 1750, our Baroque period, is a long time in the history of music, however, and there has been much difficulty about giving the same label to Monteverdi’s music and to Händel’s or to Henry Purcell’s.

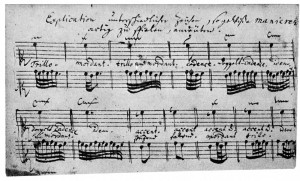

The Church, in her zeal to appeal to the common people, wanted music that was simpler in texture than the polyphony of the Renaissance, so there was a need for a melody and accompaniment instead. The music of the Baroque, ornamented though it be, is basically a melody with chords supporting that melody.

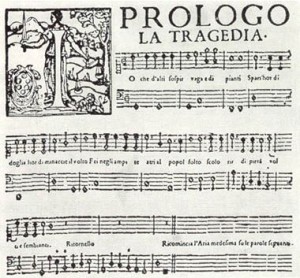

The Florentine Camerata was a group of humanists, musicians, poets and intellectuals in late Renaissance Florence who gathered under the patronage of Count Giovanni de’Bardi to discuss the arts, especially music and drama.

Their ideal was a classical musical drama that valued discourse and oration, and they deplored their contemporaries’ use of polyphony and instrumental music, discussing such ancient Greek music devices as monody, which consisted of a solo singing accompanied by a kithara.

The working out of this ideal, including Jacopo Peri’s Dafne (1597), considered to be the first opera, inspired Baroque music.

Ironic that a simple ideal of singing to the accompaniment of a stringed instrument spurred the growth of such a baroque form as opera.

Jacopo Peri’s L’Euridice was performed as part of the Marie de’Medici and Henri IV wedding celebrations in 1600.

Louis XIV personified the age of absolutism (L’état, c’est moi.) and his style of palace and manners became the model for the rest of Europe. The realities of rising church and state patronage created the demand for organized public music such as chamber music.

There was a gradual institutionalization of forms and norms, particularly in opera. As with literature, the printing press and trade created an expanded international audience for music.

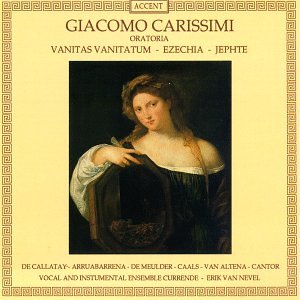

The middle Baroque period in Italy saw the emergence of the cantata, oratorio, and opera during the 1630s, the bel canto style, one of the most important contributions to the development of Baroque, which was a new concept of melody and harmony that elevated the status of the music to one of equality with the words.

The florid, coloratura monody of the early Baroque gave way to a simpler, more polished melodic style, usually in a ternary rhythm.

These melodies were built from short ideas often based on stylized dance patterns drawn from the sarabande or the courante, the gigue, the pavane.

This harmonic simplification ushered in the recitative and the aria. The most important innovators of this style were the Romans Luigi Rossi and Giacomo Carissimi, who were primarily composers of cantatas and oratorios.

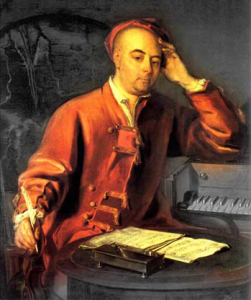

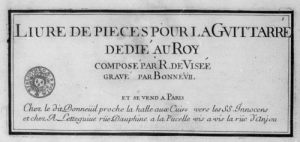

Jean-Baptiste Lully (Giovanni Battista Lulli) was a court composer, born in Firenze (Florence), to a family of millers. He used to say that a Franciscan friar gave him his first music lessons and taught him guitar. He also learned to play the violin.

In 1646, dressed as harlequin during Mardi Gras and amusing bystanders with his clowning and his violin, the boy attracted the attention of Roger de Lorraine, chevalier de Guise, who was returning to France and was looking for someone to converse in Italian with his niece, Mademoiselle de Montpensier. Guise took the boy to Paris, where the fourteen year-old entered Mademoiselle’s service and from 1647 to 1652 he served as her “chamber boy” (garçon de chambre).

Lully’s talents as a guitarist, violinist, and dancer quickly won him the nicknames “Baptiste“, and “le grand baladin” (great street-artist).

He did indeed grow into a great artist, and he collaborated with Molière on a series of comédie-ballets, and used this success to become the sole composer of operas for the king.

Lully knew what le roi Louis wanted, which explains his rapid shift to church music when the mood at court became more devout. His thirteen completed lyric tragedies are based on libretti that focus on the conflicts between the public and private life of the monarch.

Lully’s near contemporary, Arcangelo Correlli, improved musical technique by insisting on better intonation. The style of execution introduced by Corelli and preserved by his pupils was of vital importance for the development of violin playing. It has been said that the paths of all of the famous violinist-composers of 18th and 19th centuries Italy led to Arcangelo Corelli who was their “iconic point of reference” and he created a beautiful flow of melody in purely instrumental music, such as the concerto grosso.

Lully was the man at court, but Corelli published widely and had his music performed all over Europe.

The concerto grosso is built on strong contrasts— sections alternate between those played by the full orchestra, and those played by a smaller group.

There were sharp jumps between loud and soft. Fast sections and slow sections were juxtaposed against each other.

Antonio Vivaldi studied with Corelli and later composed hundreds of works based on Corelli’s trio sonatas and concerti.

Meanwhile in England, Henry Purcell produced a profusion of music and was deservedly popular in his lifetime. Purcell was a fluid composer, able to shift from simple anthems and useful music such as marches, to grandly scored vocal music and music for the stage. He was very prolific and was also one of the first great keyboard composers, whose work still has influence and presence. I played many of his pieces on the guitar and still love them. When I was 18, I used to go to a place called The Old Spaghetti Factory in North Beach on Sunday nights and listen to a small ensemble conducted by Donald Pippin play Purcell’s music.

Dietrich Buxtehude was not a creature of court but he a was church musician, holding the posts of organist and Werkmeister at the Marienkirche at Lübeck. He organized and directed a concert series known as the Abendmusiken, which included performances of sacred dramatic works regarded by his contemporaries as the equivalent of operas.

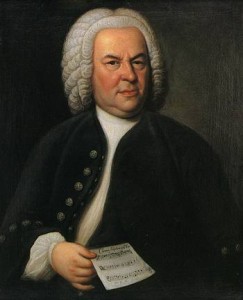

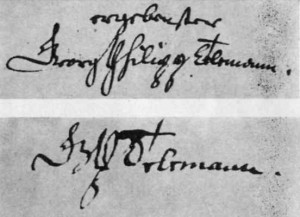

Johann Sebastian Bach was, of course, the towering figure of Baroque music. During his life, he was better known as a teacher, administrator and performer than composer, being less famous than either Handel or Georg Philipp Telemann.

In 1723 Bach settled at the post he was associated with for virtually the rest of his life: cantor and director of music for Leipzig. His varied experience allowed him to become the town’s leader of music both secular and sacred, teacher of its musicians.

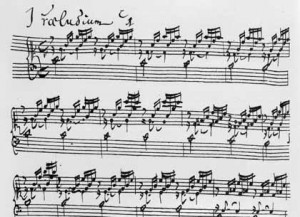

Bach composed a church cantata for every Sunday and holiday of the year. He also created the St. John Passion, the St. Matthew passion, the Christmas Oratorio and the Mass in B minor, works that seem to be divine.

Bach expanded the depths and the outer limits of the Baroque homophonic and polyphonic forms. He used every contrapuntal device possible and every acceptable means of creating webs of harmony with the chorale. His fugues, preludes and toccatas for organ, and the baroque concerto forms, have become fundamental in both performance and theoretical technique. He summed it all up and brought it forward.

These are all composers whose music I was playing in various recorder ensembles at the time that we began Big Brother and the Holding Company.

Georg Philipp Telemann was a particular favorite. He was almost completely self taught and he had backed into a career in music.

In complete contradistinction to Bach, Telemann’s personal life was always troubled: his first wife died only a few months after their marriage, and his second wife had extramarital affairs and accumulated a large gambling debt before leaving him.

Telemann was one of the most prolific composers in history and was considered by his contemporaries to be one of the leading German composers. He remained at the forefront of all new musical tendencies and his music is an important link between the late Baroque and early Classical styles. Like Händel, Telemann knew everybody and did everything. Bach was his friend, but so was everyone.

Have you ever looked at a painting or a sculpture from before the age of photography and wondered if the subject really looked like that? One way to verify such a question is to look at a depiction of a person by two different artists. Here is Giuliano Finelli’s portrait of Cardinal Scipione Borghese.

And here is Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s depiction of the same man. Uncannily similar, aren’t they? The bust above (Finelli’s) seems to depict a man who is more tired. His gaze is below eye level. Bernini’s portrait is more jaunty. Even the cardinal’s hat is at attention.

Finelli had worked in Bernini’s studio.

He was the “detail man,” perhaps more fascinated with dress and ornamentation than his mentor.

Bernini’s virtuosity in carving marble and his ability to create figures that combine the physical and the spiritual make him one of the most important figures in the history of sculpture.

The Protestant Reformation (16th century) brought an almost total stop to religious sculpture in much of Northern Europe. It was literally an iconoclastic age. Statues were smashed and church decorations were pulled apart. Fundamentalism run rampant, as we see in our own time.

Partly in direct reaction to this iconoclasm, sculpture was deemed as important in the Baroque as it was in the late Middle Ages. In the 18th century much sculpture continued on Baroque lines. The Fontana di Trevi was only completed in 1762 from a design by Bernini (1598–1680). His architecture, sculpture and fountains are examples of the highly charged characteristics of Baroque style. The sculpture was cut deep in the Baroque to give a dramatic light and shadow effect.

Groups of figures spiraled around an empty central vortex, or reached outwards into the surrounding space.

There were often multiple ideal viewing angles, and a general continuation of the Renaissance move away from the relief to sculpture created in the round, and designed to be placed in the middle of a large space.

Even when he was actually doing a relief, Bernini made his subject virtually jump out of the frame. Notice how deeply the cuts are made in the piece, which gives an illusion of depth and heightens the emotion. The folds in the clothing are harmonized and have a personality of their own.

Artists saw themselves as in the classical tradition, but admired the more “vulgar” Hellenistic and later Roman sculpture, rather than the more stately “Classical” styles.

The Baroque period had a distinctly popular aspect. The eyelashes in this sculpture appear to be glued on. Mixed media again.

Baroque painting is often identified with Absolutism, the Counter Reformation and the Catholic Revival, but it only began that way. The existence of important Baroque art and architecture in non-absolutist and Protestant states throughout Western Europe underscores its widespread popularity.

Baroque artists chose the most dramatic point, the moment when the action was occurring. In the Renaissance, Michelangelo shows his David thoughtful and composed before battle with Goliath, but Bernini’s David is caught in the act of hurling the stone at the giant.

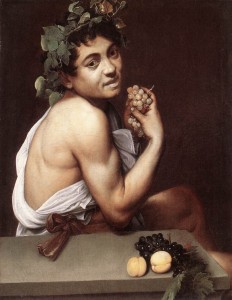

Baroque art was meant to evoke drama, emotion and passion instead of the calm rationality that had been prized during the Renaissance.

Baroque painters understood what Robert Crumb calls “the power of black.” Caravaggio painted directly from life and dramatically lit his figures against a dark background. We used to call this “nightclub lighting.” Here is Caravaggio’s depiction of the calling of Matthew, who was a tax collector, to come and follow Jesus.

And here is Hendrik Terbrugghen’s painting of the same subject.

Artemisia Gentilleschi’s beautiful paint it black version of Judith and Holofernes.

Rembrandt, who perhaps best caught the emotions of the soul as they play out on the face, also used the power of black, the chiaroscuro, in his work.

Sacred and Profane Love by Giovanni Baglione is a truly remarkable painting, isn’t it? I’m going to copy this one of these days.

The Council of Trent (Concilium Tridentinum 1545–63), in which the Roman Catholic Church answered many questions of internal reform raised by both Protestants and by those who had remained inside the Church, addressed the representational arts in a short and somewhat oblique passage in its decrees and demanded that painting and sculpture in church contexts should depict their subjects clearly and powerfully.

This return toward to a populist conception of the function of ecclesiastical art drove the innovations of Caravaggio and the Carracci brothers, all of whom were working (and competing for commissions) in Rome around 1600, although unlike the Carracci, Caravaggio was criticised for lack of decorum in his work.

Annibale, Ludovico and Agostino Carracci.

Significantly, in the Protestant countries, genres like still life, landscape and paintings of everyday life were more important. There wasn’t a lot of work for religious painters.

I love this virtuoso style of painting used in the depiction of ordinary life.

This is a Spanish version of everyday life, Diego Velázquez’ Old Woman Frying Eggs.

Jan Lievens who reminds me of Frans Hals.

And Hals’ portrait of Willem Heythuijsen (1634).

Peter Paul Rubens’ almost lubricious painting of a horse.

Nicolas Poussin was the leading painter of the classical French Baroque style, although he spent most of his working life in Rome. His work is characterized by clarity, logic, and order. Poussin likes line more than color.

Salvator Rosa is off in some beautiful mystic place by himself. Silence is better than talk, says his placard.

Caspar Netscher, a Dutch artist, knows how to paint a pretty woman.

And two “surrealist” works, this one by Rembrandt van Rijn.

And this by Jan Steen, The World Turned Upside Down.

On 1 January 1660, Samuel Pepys began to keep a diary. He recorded his daily life for almost ten years. The women he pursued, his friends and his dealings are all laid out. His diary reveals his jealousies, insecurities, trivial concerns, and his fractious relationship with his wife. It is an important account of London in the 1660s and probably the best diary in the English language. The Baroque time in England is known as the Restoration because of the reinstatement of King Charles II to the throne, so I am not completely sure that any of these people would be considered “Baroque,” even though their lifespans fall within the period 1600 – 1750.

Two of my favorite people ever, James Boswell and Samuel Johnson, were born in the Baroque era, and much of Boswell’s work is Baroque and beyond. Many of the episodes he narrates are as scary, outré, melodramatic, passionate and emotional as any Baroque painting or sculpture, only they are real life and told in a style that is as precise and vivid as Bernini’s or Bach’s.

Boswell’s journals are amazing, real and in three dimension. He puts you there. His Life of Samuel Johnson is the greatest biography in English and maybe in any language. I read it over and over and always find something new and worthwhile in it.

Virginia Woolf called Fanny Burney “the mother of English fiction,” and is she ever. She wrote four novels that are as good or better than anyone else’s and her narration of her mastectomy is probably more Baroque than anything you would want to read. It is a searing document, honest and terrifying. Madame d’Arblay, as she was known in later life, came from a noted family of musicians and her observations on music are most interesting.

Restoration literature includes both Paradise Lost and the Earl of Rochester’s Sodom, the high spirited sexual comedy of The Country Wife and the moral wisdom of Pilgrim’s Progress, so this time in England doesn’t always fit well with the Baroque period on the Continent.

John Locke wrote his Two Treatises on Government at this time which also saw the founding of the Royal Society and the chemstry, the experiments and holy meditations of Robert Boyle.

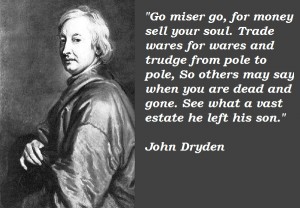

John Dryden, who practically invented literary criticism, is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the Age of Dryden. Not incidentally, newspapers and coffeehouses came into being at this time.

The official break in literary culture caused by censorship and radically moralist standards under that savage group of fundamentalists, Cromwell’s Puritans, created a gap in literary tradition, allowing a seemingly fresh start for all forms of literature after the Restoration.

During the Interregnum, the royalist forces attached to the court of Charles I went into exile with the twenty-year-old Charles II, and saw for themselves the Baroque arts of continental Europe.

Hortense Mancini, Duchess of Mazarin, arrived at the court of Charles II, in September of 1675, upon his invitation. She was well known as a patron of literature and the fine arts.

Nell Gwynne, “pretty, witty Nell,” as Samuel Pepys called her, had a comedic talent and a shrewd understanding of her time. Pepys puts these words in Nell’s mouth: ” ‘I was but one man’s whore, though I was brought up in a bawdy-house to fill strong waters to the guests; and you are a whore to three or four, though a Presbyter’s praying daughter!’ which was very pretty.”

Aphra Behn was not only the first professional female novelist, but she may be among the first professional novelists of either sex in England. Behn’s most famous novel was Oroonoko in 1688. This was a biography of an entirely fictional African king who had been enslaved in Suriname, where Behn had actually lived. She explores slavery and gender in a racy way. Vita Sackville-West called Behn “an inhabitant of Grub Street with the best of them.”

The most famous plays of the early Restoration period are the unsentimental or “hard” comedies of Dryden, William Wycherley, and George Etherege, which celebrate an aristocratic lifestyle of unremitting sexual intrigue and conquest.

The term Augustan literature derives from authors of the 1720s and 1730s, who responded to a term that George I used for himself.

While George I meant the title to reflect his might, the literary people instead saw in the term a reflection of Rome’s transition from rough and ready literature to the highly political and highly polished literature during the time of Caesar Augustus, Imperator Caesar Divi F. Augustus (Caius Octavius).

Because of the aptness of such a metaphore, the period from 1689 – 1750 was called “the Augustan Age” by critics throughout the 18th century, including Voltaire and Oliver Goldsmith, who “wrote like an angel, but talked like Poor Poll,” in the words of Samuel Johnson.

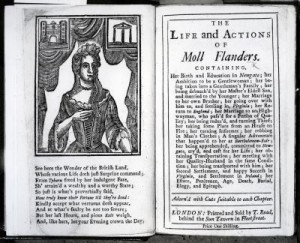

This was the time when the English novel developed into a major art form. Daniel Defoe, who had been a journalist writing criminal lives for the press, began to write fictional criminal lives in books like Roxana and Moll Flanders.

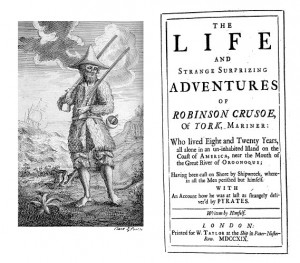

Defoe also wrote a fictional treatment of the travels of Alexander Selkirk called Robinson Crusoe (1719).

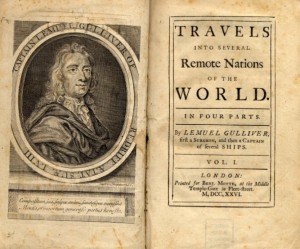

Jonathan Swift’s prose style is unmannered and direct, with a clarity that few contemporaries matched. He was a profound skeptic about the modern world, but he was similarly profoundly distrustful of nostalgia. He saw in history a record of lies and vanity, and he saw in the present a madness of vanity and lies. I read Gulliver’s Travels when I was ten and was amazed at Swift’s prose style. There is such a sensible precision to it that is perfect for making the unreal real as he did in that book.

Swift believed that Christian values were essential, but these values had to be muscular and assertive and developed by constant rejection of smooth talking marketers and bogus preachers. In A Tale of A Tub, Swift detailed his skeptical analysis of the claims of the modern world.

After his “exile” to Ireland, Swift reluctantly began defending the Irish people from the predations of English colonialism. A Modest Proposal and The Drapier Letters actually provoked riots and arrests. Swift, who otherwise had no love for Irish Catholics was outraged by the English abuses and barbarity he saw around him.

An effect of the Licensing Act was to cause more than one aspiring playwright to switch over to writing novels. Henry Fielding began to write prose satire and novels after his plays could not pass the censors.

The pious Samuel Richardson had produced a novel intended to counter the deleterious effects of the new novel in his Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740). Henry Fielding attacked the absurdity of Richardson’s book with two of his own works, Joseph Andrews and Shamela, and then countered Richardson’s Clarissa with Tom Jones.

Laurence Sterne attempted a Swiftian novel, Tristram Shandy, which has always eluded me somehow, although I can see/feel that it is a very original work, much more adventurous and creative than Swift, but never really my cup of tea. I took it as a cock and bull story.

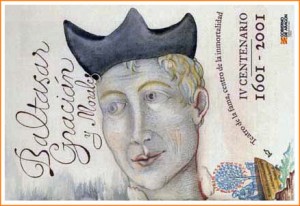

Meanwhile, across the Channel and to the south, a Spanish Jesuit, Baltasar Gracián y Morales, S.J. (January 8, 1601 – December 6, 1658) was the most representative writer of the Spanish Baroque literary style known as Conceptismo, of which he was the most important theoretician. His Agudeza y arte de ingenio (Wit and the Art of Inventiveness) is a poetic rendering of the conceptist style.

Gracián is now best known for the Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia, which was written in 1637.

The book is a collection of 300 maxims (aforísmos), each with a commentary, on various topics giving advice and guidance on how to live fully, advance socially, and be a better person.

A bad manner spoils everything, even reason and justice: a good one supplies everything, gilds a No, sweetens a truth, and adds a touch of beauty to old age itself.

The wise does at once what the fool does at last.

Beauty and folly are generally companions.

The sole advantage of power is that you can do more good.

Be content to act and leave the talking to others.

Things do not pass for what they are, but for what they seem. Most things are judged by their jackets.

Friendship multiplies the good in life and divides the evil.

After the Renaissance which was the classical period of restraint and grace, the Baroque was twisted, emotional and extreme. The Baroque was the Hellenistic period of our time.

After the Baroque came a short period of return to the classical ideal, Neoclassicism, which was a mostly French and rather short lived pastiche of Renaissance values which evolved into the Academic style of the 19th century.

After that, le déluge: impressionism, surrealism, Expressionism, the 20th century, Abstract Art, Pop Art.

Who reads, rules.

______________________________________