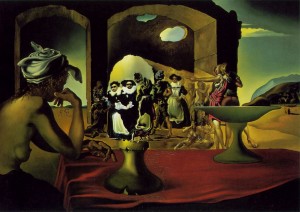

One of the early contributors to an analysis of the energy component that would be used in the formula E = mc2

Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, marquise du Châtelet (17 December 1706 – 10 September 1749) was a mathematician, physicist, and author during the Age of Enlightenment.

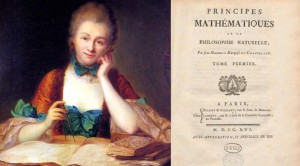

Her translation of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica is still considered the standard French version.

Émilie was intellectual and very lively. She played the harpsichord, sang opera, she had a gift for the dance and she was an amateur actress. She was beautiful, charming, and seriously intelligent.

She spoke very rapidly and read even more rapidly. When she couldn’t afford more books, she used her mathematical skills to devise highly successful strategies for gambling.

Young Émilie de Breteuil lived with her family in an apartment with 30 rooms overlooking the Tuileries gardens in Paris.

When Émilie was a child, her father, Louis Nicolas le Tonnelier de Breteuil, held the position of the Principal Secretary and Introducer of Ambassadors to King Louis XIV. He held a weekly salon on Thursdays, to which well-respected writers and scientists such as Fontenelle, the perpetual secretary of the Académie des Sciences, were invited.

Her father arranged for Fontenelle to visit and talk about astronomy with Émilie when she was 10 years old.

She also had training in physical activities such as fencing and riding, and as she grew older, her father brought tutors to the house for her.

As a result, by the age of twelve Émilie was fluent in Latin, Greek and German. She was later to publish translations into French of Greek and Latin plays and philosophy.

Her brothers and sisters were fairly normal people for the time, but Émilie was different, as her father wrote: “My youngest flaunts her mind, and frightens away the suitors.”

Émilie, however, had many suitors. At the age of 19, she chose one of the least objectionable courtiers as a husband, the Marquis Florent-Claude du Chastellet-Lomont. The marriage was a pro forma arrangement, and in the custom of the time, her husband accepted her having affairs while he was away.

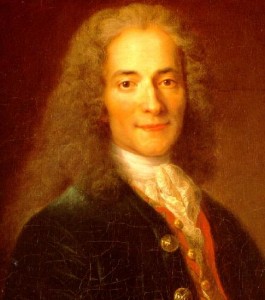

When she was a 27-year-old mother of three, Émilie du Châtelet began perhaps the most passionate affair of her life, a true partnership of heart and mind. Her lover was none other than Voltaire, perhaps the most renowned intellectual of the Enlightenment movement. “In the year 1733 I met a young lady who happened to think nearly as I did.”

She and Voltaire shared deep interests: in political reform, in fast talk, and, above all, in advancing science as much as they could.

Voltaire wrote that Émilie du Châtelet had “a soul for which mine was made.”

Together, du Châtelet and Voltaire turned her husband’s château at Cirey, in northeastern France, into a base for scientific research with the most sophisticated equipment on the market (a rotary evaporator would have been a steal back in the day – to give an example). with a library comparable to that of the Academy of Sciences in Paris, as well as the latest laboratory equipment from London.

Émilie gave up her life in Paris for Votaire and joined him at Cirey. Thus began one of the greatest intellectual and romantic relationships of the 18th century between these two exceptional people.

The intellectual feverishness, always present when Émilie was, prompted the philosopher Immanuel Kant to sneer that such a woman “might as well have a beard,” and Voltaire himself, having received solo title-page credit for a book he privately admitted she practically dictated to him, declared that the marquise was a great man whose only shortcoming was having been born female. This may hearten the rest of us, because it proves that even great men can be stupid sometimes.

When Émilie and Voltaire engaged in their teasing, mock battling, fast talking, it was a contest between equals.

Émilie du Châtelet was the real scientist, the real investigator of the physical world, and the one who decided that there was one key question that had to be turned to at this time: what is energy?

Most people felt energy was already sufficiently understood. Voltaire had covered the seemingly ordained truths in his own popularizations of Newton: an object’s energy is simply the product of its mass times its velocity, or mv1. If a five-pound ball is going 10 mph, it has 50 units of energy.

But Émilie du Châtelet knew there was a competing, albeit highly theoretical view proposed by Gottfried Leibniz, the great German natural philosopher and mathematician. For Leibniz, the important factor was mv2. It’s the ‘per second per second’ aspect of the formula that is important. This seems to hold true for many aspects of the natural world. Forces aren’t added to each other, they are squared of each other.

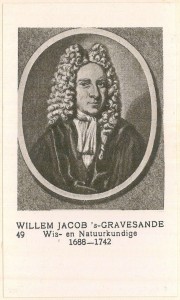

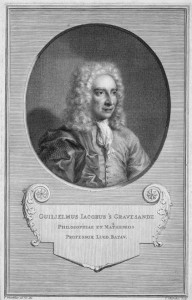

Du Châtelet and her colleagues found the decisive evidence in the recent experiments of Willem ‘s Gravesande, a Dutch researcher who’d been letting weights plummet onto a soft clay floor. If the simple E = mv1 was true, then a weight going twice as fast as an earlier one would sink in twice as deeply. One going three times as fast would sink three times as deep.

But that’s not what ‘s Gravesande found. If a small brass sphere was sent down twice as fast as before, it pushed four times as far into the clay. It if was flung down three times as fast, it sank nine times as far into the clay. In other words, we’re talking about a geometric progression and not an arithmetical one.

Thus, ‘s Gravesande established that the correct expression for the “live force” of a body in motion (today called its kinetic energy) is proportional to mv2.

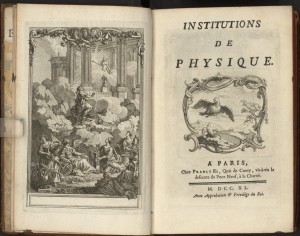

Du Châtelet deepened Leibniz’s theory and then embedded the ‘s Gravesande’s results within it. Now, finally, there was a strong justification for viewing mv2 as a fruitful definition of energy.

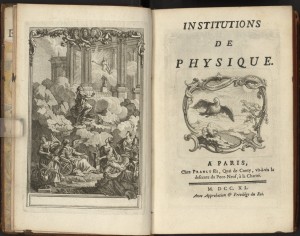

These drawings are from du Châtelet’s Institutions physiques, her elaboration on the ideas of Leibniz. She finished a major commentary on Newton just before her death.

Newton and Voltaire believed that “energy” was the same as momentum and therefore proportional to velocity.

In classical physics the correct formula is  , where

, where  is the kinetic energy of an object,

is the kinetic energy of an object,  its mass and

its mass and  its velocity.

its velocity.

Some commentators have perceived this as a precursor to the  multiplier in Einstein’s mass-energy formula, and indeed

multiplier in Einstein’s mass-energy formula, and indeed  is the first term in the binomial expansion of the relativistic kinetic energy expression.

is the first term in the binomial expansion of the relativistic kinetic energy expression.

Émilie du Châtelet was one of the leading interpreters of modern physics in Europe as well as a master of mathematics, linguistics, and the art of courtship, and, really, just about anything else that caught her attention.

But there was one thing she couldn’t control. In April of 1749, she wrote to Voltaire, “I am pregnant and you can imagine … how much I fear for my health, even for my life … giving birth at the age of forty.”

It should be said that Voltaire was not the father of this child to be. He knew that Émilie had many liaisons, but that didn’t affect his regard for her.

Although she might have, Émilie didn’t rage at the clear incompetence of her era’s doctors who often didn’t even wash their hands before participating in a medical procedure.

And remember that at that time there were no antibiotics and no anesthetics.

Émilie merely noted to Voltaire that it was sad to be leaving this world before she was ready. Think what she could have accomplished if she had had forty years more to live.

She survived the birth the next fall, but infection set in, and within a week she died.

Émilie was a brilliant and learned woman, known all over Europe for her translation of Newton. Her love affair and pregnancy created scandal and inspired satirical mirth. Her death was a shock to everyone.

Voltaire was beside himself: “I have lost the half of myself—a soul for which mine was made.”

See you next week?

Sam Andrew

__________________________________________________________