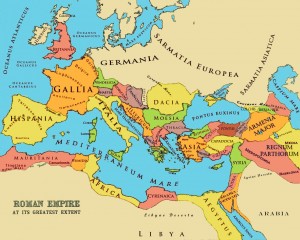

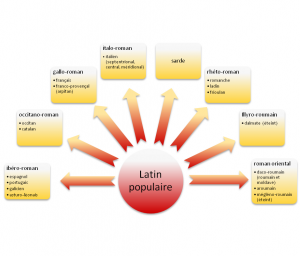

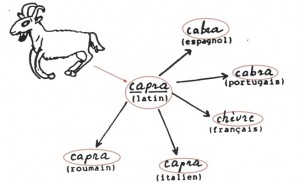

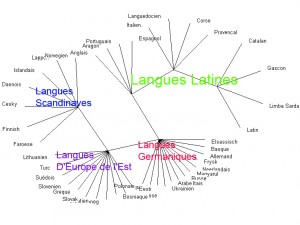

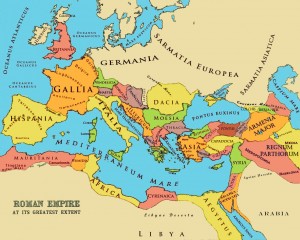

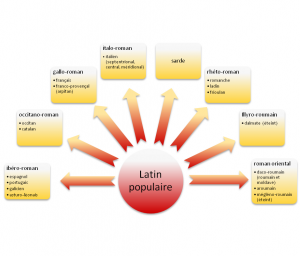

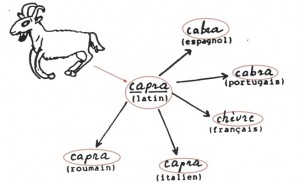

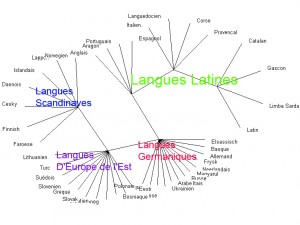

The Romans left their language behind everywhere they went. They didn’t force anyone to learn it. Everyone wanted to speak Latin, the language of opportunity and success.

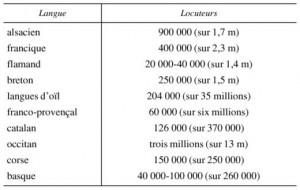

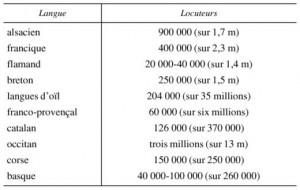

In time, Latin, became Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French and Romanian.

And also Catalan, Occitan, Provençal, Languedocien, Romanche, Corsican, Wallon, Venetian and Sicilian.

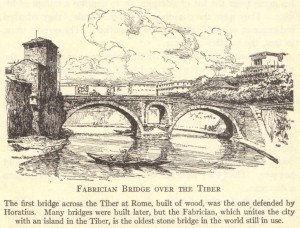

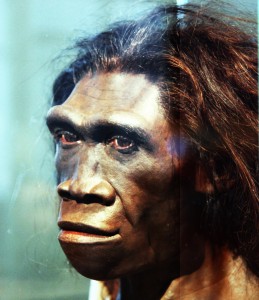

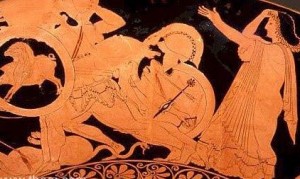

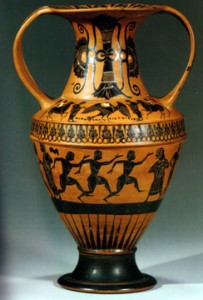

Rome began as a muddy, swampy village surrounded by the brilliant Etruscan civilization on one side and the no less prestigious Greek colonies on the other.

The history of Rome begins like a fairy tale with a prince and a goddess and continues with legendary stories and historical realities.

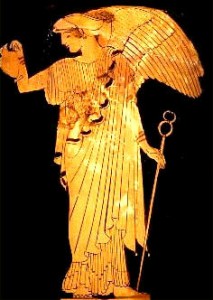

Aeneas ( Αἰνείας, Aineías, derived from Greek Αἰνή meaning “to praise”), the son of the prince Anchises, and Venus Aphrodite, brings his colony from Troy to Italy, as Virgil tells us in Book One of the Aeneid.

Two newborns, Romulus and Remus, are abandoned along the Tiber and suckled by a she wolf. Romulus kills Remus and becomes the first king of Rome.

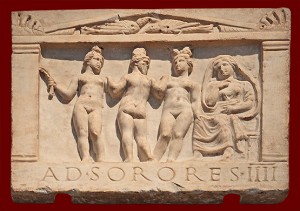

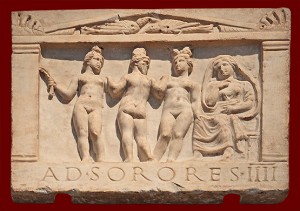

There is a rape of young women from the nearby Sabine people. The women are kidnapped to populate Rome.

A great sewer (the Cloaca Maxima) is built to drain the marshes and the Forum is created, which becomes the center of Roman life.

There is a revolution (509 BCE) and the monarchy is abolished to make way for the Republic. The government is headed by two consuls elected by the citizenry and advised by a senate. A constitution based on the separation of powers and checks and balances is developed. Public offices are held for one year, and dates in Roman history are often stated to be when so and so was consul.

The Republic will last for five centuries (from the 6th to the first century BCE) to be succeeded by the Empire which will also last for five centuries until the fall of the Western Empire in 476 CE. The Empire’s beginning is usually dated from the declaration of Julius Caesar as permanent dictator in 44 BCE.

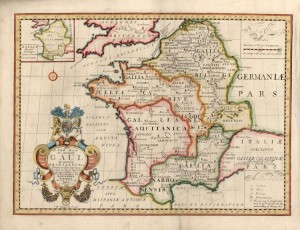

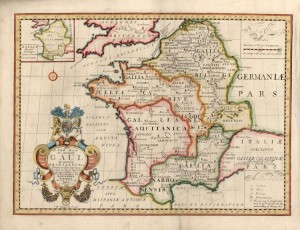

Rome conquered Transalpine Gaul (Provincia Narbonensis now called Provence) in 120 BCE and northern Gaul in 58 – 50 BCE, so the Romans were in Gaul longer than they were anywhere else.

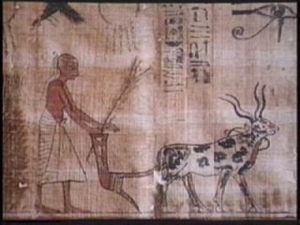

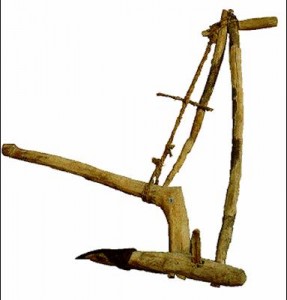

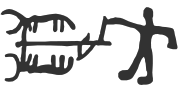

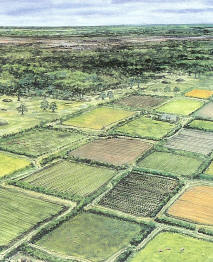

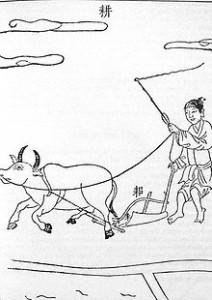

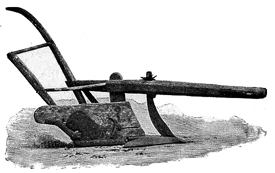

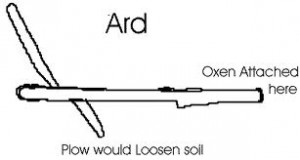

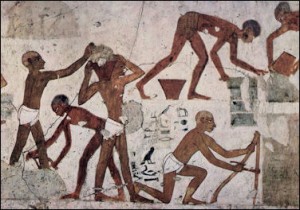

Romans were farmers in the beginning and their language was based in the soil. The verb CERNERE (to see, to discern), for example, originally meant “sift.”

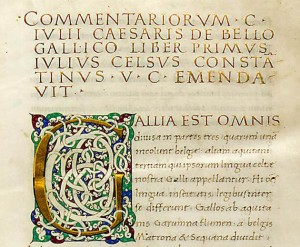

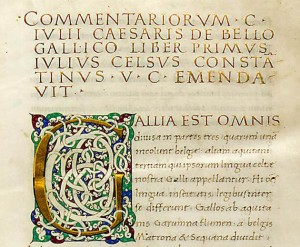

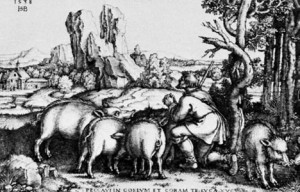

COLERE or INCOLERE which is found in the word “agricola,” farmer, originally meant cultivate, but Caesar uses it in the opening sentence of his book to mean “live” or “inhabit.”

Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres: unam quarum Belgae incolunt. All Gaul is divided into three parts: one of which the Belgians inhabit.

The verb PUTARE originally meant prune or trim. Look where it is now: compute, dispute, repute, deputy, putative.

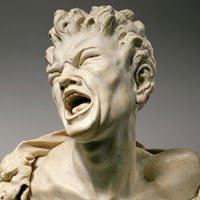

DELIRARE originally meant to leave the LIRA, the furrow. The word became delirium, delirious, délirer. That’s leaving the furrow with a vengeance.

RIVALIS was an adjective for RIVUS, the bank of a river ( rive gauche). Two people who shared the water in that river were rivals.

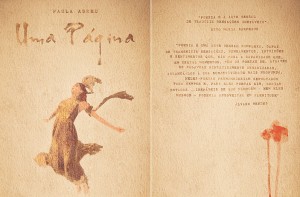

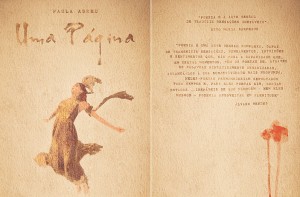

A PAGINA was a grape arbor, a group of vines arranged in a rectangle. Then it became a page of papyrus, a page containing one column of writing.

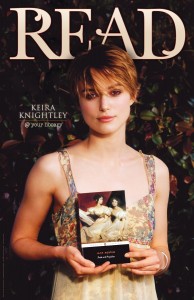

LIBER (book) originally was the tissue between the bark and the tree. The first books in Europe were written on “beechen” tablets. (Buch in German originally meant the beech tree as does our “book.”)

LEGERE Cueillir To pick, pluck, gather, harvest. This word LEGERE later took on the meaning of levy, draft, and a LEGIO (legion) is called that because the soldiers were levied upon the general population.

The past participle of LEGERE is LECTUS, so all of the elect, lecture, dialect, select, lectern, collect meanings come from LEGERE also.

LEGERE became the word for “read.” Lire, leer, leggere (Italian). When you read, you are harvesting words and meanings.

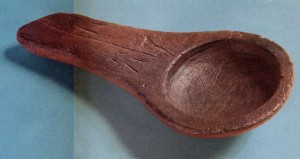

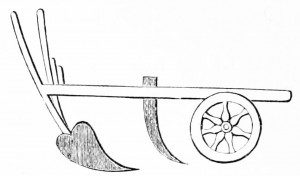

The people in France (Gallia, Gaul) finally spoke Latin, of course, but before they did they loaned some of their words to the Romans. CARRUS (a chariot with four wheels) was Gallic, as was BENNA, a kind of wagon with four wheels, which became benne the word in French for “bucket” or “scoop.”

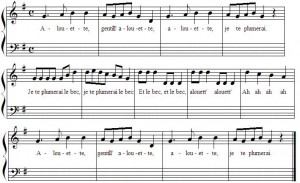

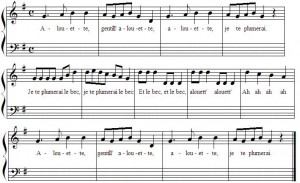

Other Gallic words brought into Latin were ALAUDA, lark, alouette; BECCUS, beak; CAMBIARE, exchange, barter (which became “buy” in Italian and Spanish).

BRACAE, breeches, britches, pants. The Romans didn’t wear them, but the Celts did. They lived in a colder climate. The word became brache in Italian and bragas in Spanish. In modern French it’s braies.

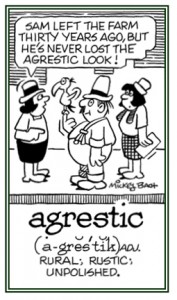

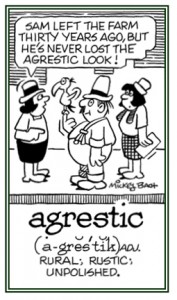

There were two Latins, the Latin of the intellectuals URBANITAS and the Latin of the streets and fields RUSTICITAS.

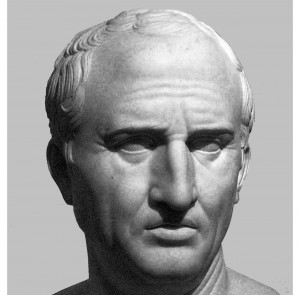

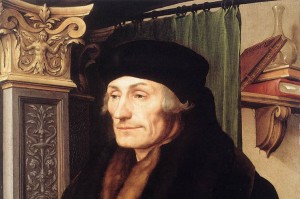

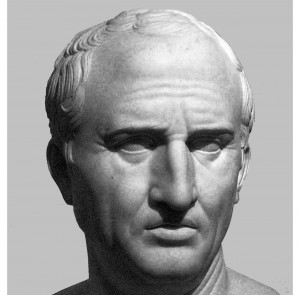

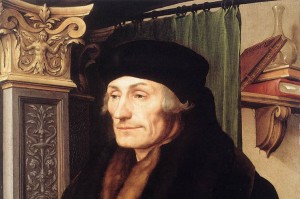

The Latin of Cicero (3 January 106 BCE – 7 December 43 BCE) was a dead language even when it was alive. There was an agreement not to change it, and, remarkably, no one changed it for centuries. I can read Latin from the time of Cicero, but can only read my own language, English, in Beowulf , written almost a thousand years later, with great difficulty when I can read it at all.

RUSTICITAS, the Latin language of the people, changed constantly all through Roman history.

The extensive use of elements from vernacular speech by the earliest authors (Plautus, for example) and inscriptions of the Roman Republic make it clear that the original, unwritten language of the Roman monarchy was an only partially deducible predecessor to vulgar Latin. Very early on, this sermo rusticus (also known as sermo plebeius, sermo vulgaris, sermo cotidianus or just sermo usualis) already had many of the features of French, Spanish, Italian and the rest.

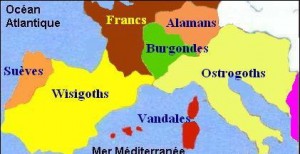

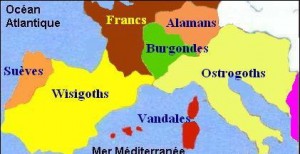

Here are some pairs of words that have the same meaning from upper and lower Latin. Guess which ones came down into French: AEQUOR and MARE (sea); AGER and CAMPUS (field); CRUOR and SANGUIS (blood); EQUUS and CABALLUS (horse); LETUM and MORS (death); SIDUS and STELLA (star); TELLUS and TERRA (terrain, earth, soil); MAGNUS and GRANDIS (big); FERRE and PORTARE (to carry, to transport). This would be easier to tell with Spanish or Italian. With French this is a little harder to see because French has changed more than any other Romance language. In fact, French is the most Germanic of the Romance languages. The very word “France” comes from the Franks, a Germanic tribe.

For the word “house,” the Romans had at least four terms: DOMUS (domicile) was the house and everything in it. AEDES (edifice) just meant the building itself. VILLA denoted a farm or agricultural property, and CASA was a cabin or a (thatched) cottage. Which term came down into the Romance languages? The humblest, of course. CASA is exactly the same in Portuguese, Italian and Spanish and in French when you say “chez nous,” you are using the Gallic form of CASA.

When I lived in New York, there was a restaurant around the corner from me called La Chaumière, which is the exact French translation of the Latin CASA.

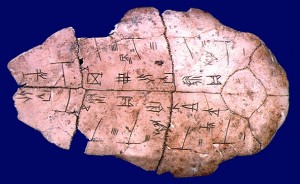

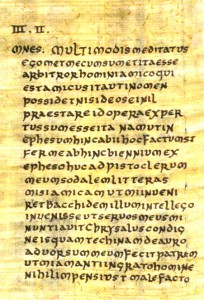

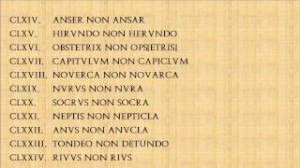

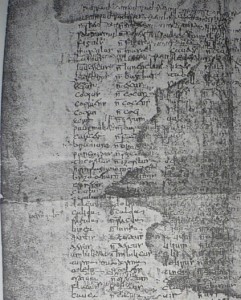

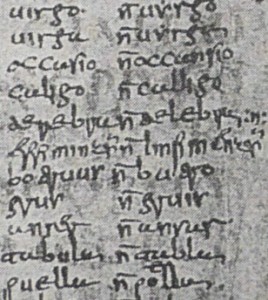

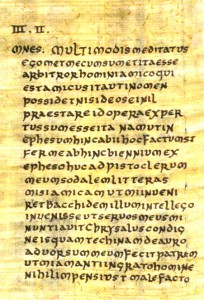

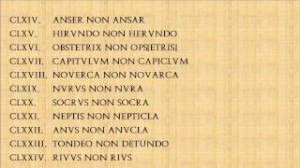

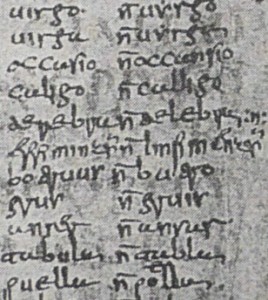

There are books, or tablets, really, from Roman times where people are taught what and what not to say.

One of the most well known is the Appendix Probi, which reads like a schoolmaster’s spelling correction book. It would be as if today a teacher published a manual with some of the following strictures: say is not, don’t say ain’t; say You gave it to whom, don’t say You gave it to who; say Where is that? don’t say Where is that at? ; say He and I did it, don’t say Him and me did it; say between her and me, don’t say between her and I. (I hate to write these and I can feel the pain of the person who wrote the Appendix Probi. It’s a losing battle, and it always was.)

These correction books are a vivid snapshot of a language in evolution. Say VIR (man) not VYR. Say SPECULUM (mirror) not SPECLUM. Say VINEA (vine) don’t say VINIA.

Say COLUMNA (column) not COLOMNA. Say NUNQUAM (never) don’t say NUNQUA. Say HOSTIAE don’t say OSTIAE (proof that the H was already beginning to disappear.)

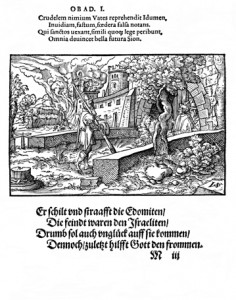

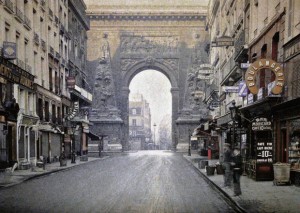

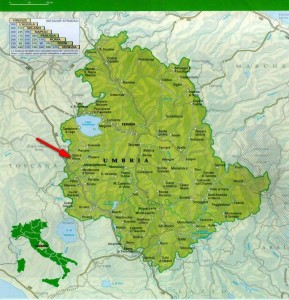

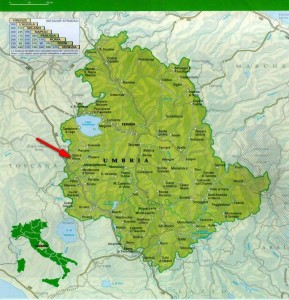

Città della Pieve City of the People

Say RIVUS (bank of a river) not RIUS (“river” in Spanish is “rio.”); Say PLEBES not PLEVIS (b and v were already beginning to be confused. Big Brother played in an Umbrian town called Città della Pieve. Pieve is what PLEBES, people, had become by the time we got there. (The LATIN L became I in Italian. Clara = Chiara.)

Say CIVITAS (city) not CIVITÀT (ciudad is Spanish for city) and certainly not CITTÀ. Say AQUA not ACQUA. Say PAUPER MULIER (poor woman, pauvre femme) not PAUPERA MULIER (changing third declension adjectives and pronouns to the first and second declensions).

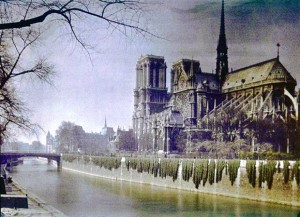

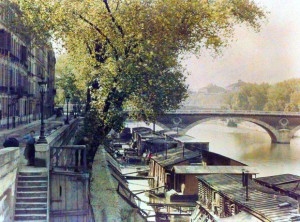

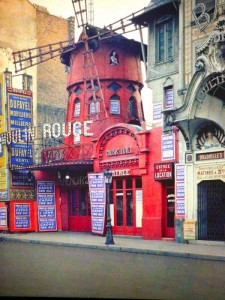

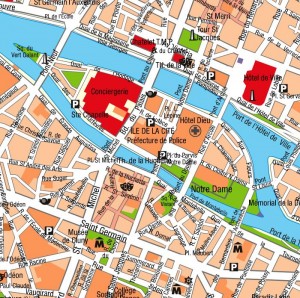

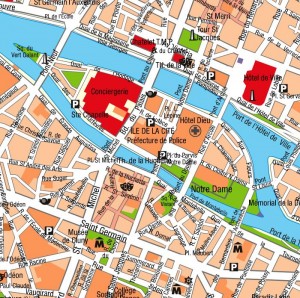

Île de la Cité WAS Paris for a very long time. Nôtre Dame was begun in 1163. In 1963, I stood in a large group of people right about here and we heard and saw a son et lumière presentation of the catheral’s 800 year old history. In Latin her name would be Nostra Domina.

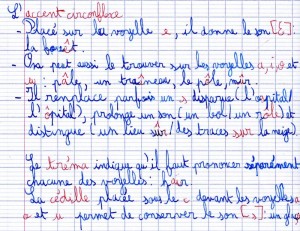

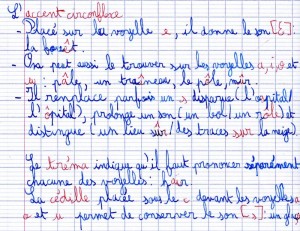

The accent circonflexe in French very often tells you that an s was there originally: île, hôte, août, hâte, arrêt, bête, fête, forêt. Put an s into each of these words and you will see very quickly what they mean.

For a linguist these prescriptive “corrections” are a delight, because in almost every case, what the people are taught NOT to say is what they are actually saying (otherwise why bother to correct them?) and these “mistakes” will be passed down into French and the other daughters of Latin.

Some rules from these early prescriptive wordbooks: Say AURIS, don’t say ORICLA. Say FRIGIDA, don’t say FRICDA. Say CALIDA, don’t say CALDA. Say MENSA, don’t say MESA. These rules show you what people were saying (and spelling) then.

Guess which forms came down into the Romance Languages? MESA, you know, if you live in the Southwest of the United States. ORICLA became oreille, oreja. FRICDA became froid. CALDA became chaud.

A thoughtful person might be encouraged here to think of terms and forms that are forbidden in English today, and to consider how our own language is evolving.

Comparatives in Latin: DOCTUS is wise, knowing, learned. DOCTIOR is more wise, more knowing, more learned. DOCTISSIMUS is the most learned.

In French, however, these comparatives were made by using Latin MAGIS (more) and PLUS (plus). More than my own life. Docte. Plus docte. Le plus docte.

Je n’en ai plus. I just don’t have any more. That’s it, I just can’t do any more.

Adverbs: IN SIMUL ensemble, AB ANTE avant, DE EX dès

When my wife Elise is in Germany, she can be heard to say, “Den Schlüssel der Toilette, bitte?” and the person at the gas station will say, “Der Schlüssel ist hier.” When Elise asks for the key to the bathroom, she uses the accusative case, because implied in her request is Ich will (I want the key to the bathroom), because “key” is the object of the sentence. The woman answers, “The key is here (der Schlüssel) which is the nominative case because “key” is the subject of the sentence.

German is an inflected language. The words can change form according to what function they perform. It’s the key to another world.

In English we have cases too, although we don’t call them that, and they are mostly seen in pronouns. He goes to the store. “He” is in the nominative case. He took his book. “His” is in the genitive case. I saw him. “Him” is in the accusative case. He, his, him are all referring to the same person, but the words change according to their function.

So, English is an inflected language too, but not as inflected as German, and neither of them is as inflected as Latin. You have probably noticed that “whom” is disappearing, so that dative/accusative case will be gone forever when the last person says it.

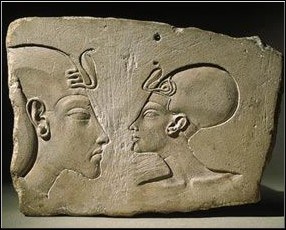

In Latin, for “Flavia picks a rose,” you can say Rosam Flavia leget. Or you can say Flavia rosam leget. Or you can say Leget Flavia rosam, or even Leget rosam Flavia, or Flavia leget rosam. They all mean Flavia picks a rose and the word order is not important because Flavia is in the nominative case and she is the subject of the sentence. Rosam is in the accusative case, and, wherever rosam is in the sentence, it will always be rose as the object of the sentence.

Similarly, to say “Flavia loves the color of the rose,” you can say Flavia colorem rosae amat, or Rosae colorem Flavia amat, or Colorem rosae Flavia amat or Amat Flavia rosae colorem. They all mean Flavia loves the color of the rose. This is Classical Latin, the language of Cicero and Caesar. The word order (syntax) is unimportant because each word has an ending that tells its function. Flavia is the subject of the sentence. Amat is the verb. Colorem is the object. And rosae is the genitive. It means “of the rose” no matter where it is in the sentence.

In the Latin of the street (RUSTICITAS), however, the endings of words, because they were almost always unaccented, began to be lost with people speaking quickly, mumbling, being drunk, being excited, being lazy… the endings dropped away early. So now what happens to the syntax? The order of the words in the sentence becomes more than important; it becomes absolutely necessary to the meaning of the phrase.

Paulus Petrum verberat means Paul hits Peter. It’s the same if you say Petrum Paulus verberat, but not if the endings in Paulus and Petrum both become -u as they did early on in street Latin. If Paulus and Petrum become Paulu and Petru, then Paulu has to go first and Petru has to follow the verb for the sentence to be most clear. Paulu verberat Petru. And the -t in verberat was lost early too, so the sentence looks like Paulu verbera Petru. This is beginning to look a lot like Spanish, French or Italian, isn’t it?

Flavia rosam amat (Flavia loves the rose) now begins to be said Flavia ama rosa, and if you say Flavia loves that rose, the sentence, even in Roman times, can be said Flavia ama(t) (il)la(m) rosa(m). Flavia ama la rosa. Then the sentence looks very much as it would in Spanish or Italian. Flavia aime la rose, as the people in Gallia would say.

In Classical Latin, murus (wall) is the subject of the sentence (nominative). Muri means “of the wall” or wall’s (genitive). Murum is the wall as the object of the sentence (accusative) and muro means “to the wall” (dative). So, there are four cases, murus, muri, murum, muro.

By the third century BCE, people in the street were saying muro(s), muri, muro, muro, and they weren’t pronouncing the s in the first case, so the word sounded the same in all the cases. We know this because of writing on tombstones, graffiti, and other places where uneducated people would write. And now to emphasize the words they would say THAT wall, rather than just wall. That = ille in Latin, and so they said (Il)le mur. Le mur is the wall in French.

Here is a message on a tombstone, date unknown: Hic quescunt duas matres, duas filias numero tres facunt et advenas II parvolas qui suscitabit cuius condicio est. Jul. Herculanus. There is a joke here, “two mothers, two daughters make the number three.” OK, it’s not a big joke, but it’s on a tombstone, where jokes are in short supply. Let’s be grateful.

There is a later inscription on a tomb in Gallia: Hic requiiscunt men bra ad duas frates Gallo et Fidencio qui fo erunt fili Magno… Both of these inscriptions show that the old declension (case) system was disappearing and would soon disappear altogether.

So, now, articles became necessary. In late Latin the definite article (the) was taken from the word for “that” ille, illa. For the indefinite article (a) the word for “one” was used. Unus, una. “The widow” is la vidua and “a widow” is una vidua. La veuve, une veuve.

Now prepositions become important. They are needed to show the relationships of the words to each other. The dative case is gone, so you have to say “to the wall,” as you do in English. Or “on the table,” or “with the drink.” The world had changed. (That’s the world… in the bubbles.)

Frederick the Great of Prussia and Voltaire made a bet who could write the shortest sentence in Latin. Frederick wrote Eo rus. (I’m going to the country.) Voltaire replied I (Go).

The French philosopher Jacques Derrida received a doctorate honoris causa from Oxford University and he wrote his discours de réception in Latin.

There were several words for “blonde” or “white” in Latin. Our friend Flavia above was so named because she was blonde (FLAVUS yellow). Also ALBUS meant white as did CANDIDUS but the French took their word BLANC from the Germanic languages. The Romans, too, borrowed “blond” from the Germans very early and Roman women bought great quantities of blonde hair from the north.

There were four or five ways to say “blue” in the mother language: CAERULEUS denoted the color of a cloudless sky. CYANEUS was a darker blue. CAESIUS, a gray-blue, a greenish blue, especially used for the color of eyes, and then there was GLAUCUS “between green and pale blue,” and VIOLACEUS, blue tending to violet, but in about the seventh century CE, the French borrowed *blao from the Germanic language.

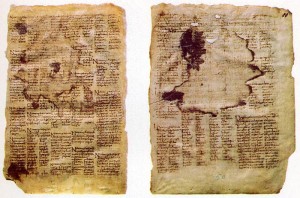

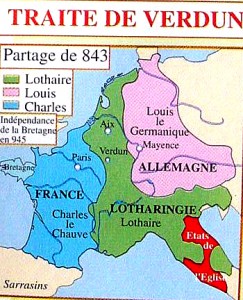

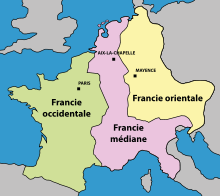

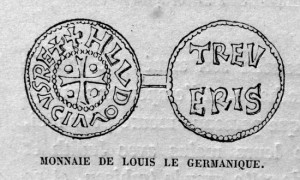

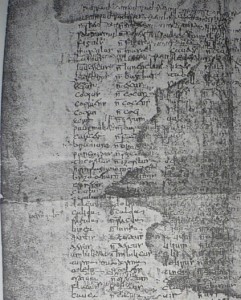

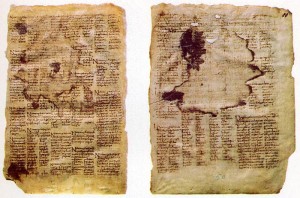

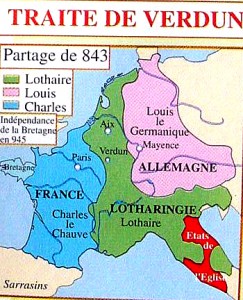

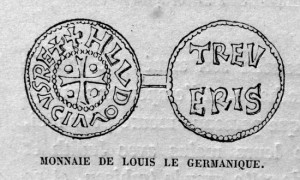

So, when did French become truly French and not a mélange of Latin and Gallic? One boundary date might be the Oaths of Strasbourg (842 CE) taken by two grandsons of Charlemagne, Louis le Germanique and Charles le Chauve to swear assistance and fealty to each other against their brother Lothaire.

These Oaths were written in the langue romane and the langue germanique. The only copy we have is from a century later, but the document is invaluable for linguists.

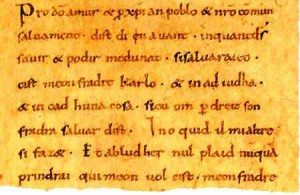

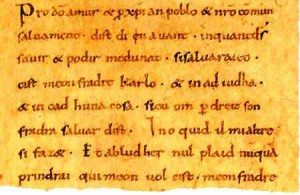

Pro deo amur et pro christian poblo et nostro commun saluament d’ist di en auant, in quant Deus sauir et podir me dunat, si saluarai eo cist meon fradre Karlo, et in aiudha et in cadhuna cosa, si cum om per dreit son fradra saluar dift, in o quid il mi altresi fazet, et ab Ludher nul plaid nunquam prindrai qui meon uol cist meon fradre Karle in damno sit.

In today’s French this would be: Pour l’amour de Dieu et pour le salut commun du peuple chrétien et le nôtre, à partir de ce jour, autant que Dieu m’en donne le savoir et le pouvoir, je soutiendrrai mon frère Charles de mon aide et en toute chose, comme on doit justement soutenir son frère, à condition qu’il m’en fasse autant, et je ne prendrai jamais aucun arrangement avec Lothaire, qui, à ma volonté, soit au détriment de mon frère Charles.

This is the way the Oath reads in la langue germanique: in godes minna ind in thes christânes folches ind unsêr bêdhero gehaltnissî fon thesemo dage frammordes sô fram sô mir got geuuizci indi mahd furgibit sô haldih thesan mînan bruodher sôso man mit rehtu sînan bruodher scal in thiu thaz er mig sô sama duo indi mit ludheren in nohheiniu thing ne gegango the mînan uillon imo ce scadhen uuerdhên

oba karl then eid then er sînemo bruodher ludhuuuîge gesuor geleistit indi ludhuuuîg mîn hêrro then er imo gesuor forbrihchit ob ih inan es iruuenden ne mag noh ih noh thero nohhein then ih es iruuenden mag uuidhar karle imo ce follusti ne uuirdhit.

In la langue romane, notice that the original is much more concise than the modern French. This is because of the survival of some cases and other similarities to Latin.

The copyist seems to have hesitated over the written form of final unaccented vowels. For aiudha (help) and cadhuna (each), he writes a.

Sometimes a, sometimes e: fradra, fradre (brother).

Sometimes e. sometimesd o: Karle, Karlo (Charles).

In Latin, the future of LAVARE was lavabo, lavabis. In French (and similarly in the other daughters of Latin) the verb “to have” (avoir) was used to make the future: laver + ai = I will wash; laver + as = you will wash; laver + a = she, he, it will wash; laver + (av)ons = we will wash; laver + (av)ez = you will wash; laver + ont = they will wash.

Sometimes a Latin word would come into French twice, once very early and then another time very late. The same thing happened with English and, in fact, some of the pairs are the same, such as frail and fragile (frêle et fragile) from FRAGILEM.

SECURITATEM sûreté et sécurité. FABRICAM came into French early as forge and then later as fabrique. FRIGIDUM froid et frigide. GRACILIS grêle et gracile (slender, slim). CADENTIAM chance et cadence. POTIONEM poison et potion. MUSCULUM moule (mussel) et muscle. MONASTERIUM moutier (obsolete) et monastère. MINISTERIUM métier et ministère. TABULAM tôle (sheet metal) et table. CLAVICULAM cheville (ankle) et clavicule. AUGUSTUM août et auguste.

Sometime early in the fifth century CE, Egeria, a Spanish nun, set out to visit as many as possible of the places mentioned in the Bible. This was in effect the first of many, many Christian pilgrimages and she decided to write about what she had seen.

The manuscript was discovered at Arezzo in 1887 by Italian scholar Gamurrini. Egeria’s descriptions of the way she was received by local dignitaries in her travels suggest that her standing in the Church was high.

No other author of her time or for long after wrote in such a lively and conversational style. It is like hearing her talk.`She writes in Latin, but it is a Latin far removed from the villas of Cicero and Caesar. Her language, the syntax, the simplicity, the excessive use of definite and indefinite articles, is well on its way to becoming French, Italian, Spanish. She’s chatty.

Cum ergo descendissimus, ut superius dixi, de ecclesia deorsum, ait nobis ipse sanctus presbyter: ecce ista fundamenta in giro colliculo isto, quae videtis, hae sunt de palatio regis Melchisedech…. Nam ecce ista via, quam videtis transire inter fluvium Iordanem et vicum istum, haec est qua via regressus est sanctus Abraam de caede Codollagomor regis gentium revertens in Sodomis, qua ei occurrit sanctus Melchisedech rex Salem.

When we had gone down from the church, as I said above, the holy priest spoke to us: You see those ruins in the fold of that hill, they are of the palace of king Mechisedech…. That path which you see passing between the river Jordan and the village, that is the way by which holy Abraham came back from the slaughter of Codollogomor, king of the peoples returning to Sodom, where holy Melchisedech king of Salem met him.

She continues: Tunc ego quia retinebam scriptum esse baptizasse sanctum Iohannem in Enon iuxta Salim, requisivi de eo, quam longe esset ipse locus. Tunc ait ille sanctus presbyter: ecce hic est in ducentibus passibus; nam si vis, ecce modo pedibus duco vos ibi. Nam haec aqua tam grandis et tam pura, quam videtis in isto vico, de ipso fonte venit. Tunc ergo gratias ei agere coepi et rogare, ut duceret nos ad locum.

Then because I remembered that it is written that Saint John had been baptizing in Enon near Salem, I asked of him how far away the place was. Then the holy priest said: It is two hundred yards away; if you wish, I will lead you there on foot. The stream which you see in the village, so large and clear, comes from that source. Then I began to thank him and ask that he should take us to the place.

This was a woman who loved to travel and who loved people. Her use of words such as HIC, IPSE, ISTE and ILLE and priest’s use of ECCE are pointing forward to la langue romane. They are attention getting and attention directing devices that are always a feature of ordinary life. Professors and academics are used to being the center of attention, and listened to, but everyday people have to build a few HEY! moments into their speech even to hope to be heard. HIC, IPSE, ISTE, ILLE, ECCE are all look at me words that call for attention.

Egeria would not have been out of place in Chaucer’s collection of pilgrims on their way to Canterbury a thousand years later.

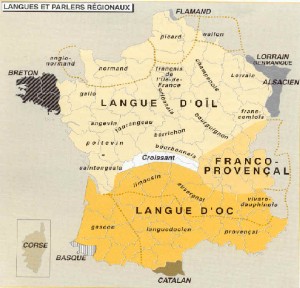

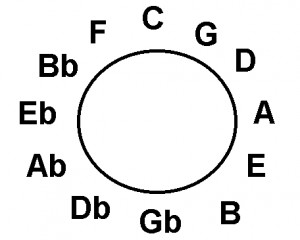

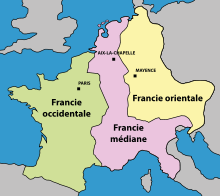

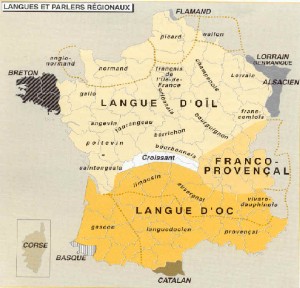

The Gallia of the Romans began to form her own language(s). The names for them were each based on the word “yes.” The languages of the former Gallia Narbonensis (Provence) had a word for “yes” that was originally HOC, “this.” If someone said, “Did you go to the market today,” and you wanted to affirm this, you simply said HOC, this.

In Latin there was no word for “yes.” People simply said “thus,” which was SIC and this evolved into “si.”

In the French of today there is this “si,” but it is only used to contradict a negative statement. If she says, “You weren’t at Monterey, were you?” I can answer, “Si, j’y suis êté.” (Yes, I was there.)

Of course, the Latin SIC (thus) came down into all of the other Romance Languages as the word for “yes.” In Portuguese: Sim. Eu gosto muito. (Yes, I like it a lot.) Spanish: Si, señor. Italian: Ma, si, lo sai che sei più bella della Avril Lavigne, davvero eh! (But, yes, you know it, that you are more beautiful than Avril Lavigne, really, eh?)

In the north of Gallia, which we can almost call France now, the phrase for “yes” was HOC ILLUD, which is something like “this that,” but it meant “yes,” and the language of Gallia Septentrionale, northern France, became known as la langue d’oïl, the language of oui. The language of HOC ILLUD.

In the 9th century romana lingua (the term used in the Oaths of Strasbourg of 842) was the first of the Romance languages to be recognized by its speakers as a distinct language, probably because it was the most different from Latin compared with the other Romance languages.

A good number of the developments that we now consider typical of Walloon, the language spoken in the environs of Belgium, appeared between the 8th and 12th centuries. Walloon “had a clearly defined identity from the beginning of the thirteenth century”. In any case, linguistic texts from the time do not mention the language, even though they mention others in the Oïl family, such as Picard and Lorrain. During the 15th century, scribes in the region called the language “Roman” when they needed to distinguish it. It is not until the beginning of the 16th century that we find the first occurrence of the word “Walloon” in the same linguistic sense that we use it today.

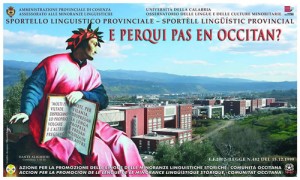

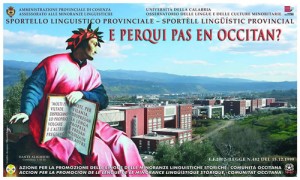

In the south of Gallia, the language was called langue d’oc, the language of HOC, which was how they said “yes” in the South. This speech became known as OCCITAN.

Oc was and still is the southern word for yes, hence the langues d’oc or Occitan languages. The most widely spoken modern Oïl language is French (oïl was pronounced [o.il] or [o.i], which has become [wi], in modern French oui).

Very early on, differences between the languages of the south and north became marked.

These differences still exist today and there have been many movements to make southern dialects (Provençal, languedocien, occitan) into languages in their own right, especially in the 19th century and especially by the writer Frédéric Mistral.

In the South, they said: cantat aqua pratu(m) In the North, it was chante eau près.

By late- or post-Roman times Vulgar Latin had developed two distinctive terms for signifying assent (yes): hoc ille (“this (is) it”) and hoc (“this”), which became oïl and oc, respectively. Subsequent development changed “oïl” into “oui”, as in modern French. The term langue d’oïl itself was first used in the 12th century, referring to the Old French linguistic grouping noted above.

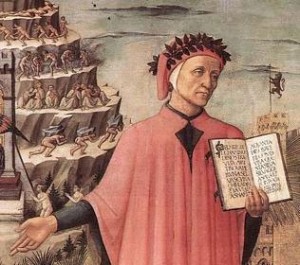

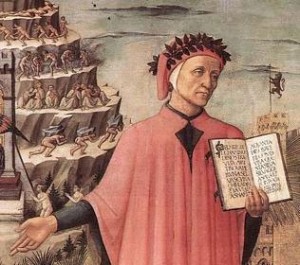

In the 14th century, the Italian poet Dante mentioned the yes distinctions in his De vulgari eloquentia. He wrote in Medieval Latin: “nam alii oc, alii si, alii vero dicunt oil” (“some say ‘oc’, others say ‘si’, others say ‘oïl’”)—thereby distinguishing at least three classes of Romance languages: oc languages. oui languages and si languages.

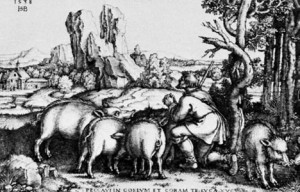

This is part of the story of the Prodigal Son in various dialects. Modern French: Son fils lui dit alors: Mon père, j’ai péché contre le ciel et contre vous; je ne mérite plus d’être appelé votre fils. Mais le père dit aux serviteurs: Allez vite chercher la plus belle robe et l’en revêtez, mettez-lui au doigt un anneau, des souliers aux pieds. Amenez le veau gras et tuez-le, mangeons et faisons liesse.

And the son said unto him, Father, I have sinned against heaven, and in thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called thy son. But the father said to his servants, Bring forth the best robe, and put it on him; and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet: And bring hither the fatted calf, and kill it; and let us eat, and be merry: For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found. And they began to be merry.

And now in Picard, one of the langues d’oïl: Sin fieu ly dit: Min pere, j’ai grament péché conte I’ciel et conte vous; et jenne su pu dinne d’éte apelai vous fieu. Alor I’pére dit à ses gins: Allez vite qére s’première robe et fourez ly su sin dos; mettez ly un aniau au douet et dés solés à ses pieds. Amenés aveucque I’viau cras et tuélle, mingeons et faigeons bonne torche.

Walloon: Et I’fils li diha: Pere, j’a pegchi conte lu ci et conte vos: ju n’so nin digne d’ess loumé vos fils. Mais l’pere diha atou ses siervans: appoirto bin vite su pu belle robe et tapo li so l’coir et metto li onne bague et des solés èze pis. Et allézo prinde lu cras vai et sul touo et s’magnans et s’fusans gasse.

Morvandiau (Nièvre): Et son fiot ly dié: Men père, y ait pécé conte le ciel et conte vous aitout, y n’ mairite pu d’eitre aipelé voute fiot. Anchitot, le père dié ai sas valots; aiportez vias sai premère robbe et vitez ly, boutez ly enne baigue au det et das soulés dans sas piés. Aimouniez aitout le viau gras et l’tuez: mezons et fions fricot.

And now we go to the langues d’oc. Here is the tale in the dialect of Auvergne: Et son fiot ly dié: Men père, y ait pécé conte le ciel et conte vous aitout, y n’ mairite pu d’eitre aipelé voute fiot. Anchitot, le père dié ai sas valots; aiportez vias sai premère robbe et vitez ly, boutez ly enne baigue au det et das soulés dans sas piés. Aimouniez aitout le viau gras et l’tuez: mezons et fions fricot.

Gascon, the language of Cyrano de Bergerac: E soun hil qu’eou digouc: Moun pay, qu’ey peccat cost’oou ceo é daouant bous: nou souy pas mes digne deou noum de boste hii. Lou pay que digouc a sous baylets: Biste, biste, pourtat sa pruméro raoubo é boutats l’oc; boutats lou la bago aou dit, e caoussats lou. Amiats lou bedet gras, é tuats lou: minjen é hascan uo gran’ hesto.

Provençal as spoken in Marseille: Et soun fieou li diguet: Moun païré aï peccat contro lou ciel et contro de vous, noun siou pas digné d’estre appelat vouestre fieou. Alors, lou péro diguet à seis domestiquos: Adduses sa premiero raoubo, et vestisses lou; mettes-li une bague oou det et de souliers eis peds. Adusés lou vedeou gras et tuas lou, man- gens e faguem boumbanco.

Franco-Provençal (Swiss, Valais, Saint-Maurice: Son meniot la y a det: Mon pere y ai petchia devant le chel et devant vo; ye ne sey pas digno ora d’être appèlo voutrom fi. Mais le père a det a son valets: Apporta ley to de suite sa première roba e la fey bota; metté ley ona baga u dey é dé solar è pia; amènà le vè grà é toa lo; mindzin é fézin granta tchiéra.

These languages still exist.

SUBIUNGO is Latin for “I subjoin,” I add to, and the subjunctive mood is so named because it is primarily used in subordinate clauses. Il faut que tu vienne. (You have to come.) If faut que j’y aille. (It’s necessary that I go there.)

In Latin all conjugations and irregular verbs have four tenses of the subjunctive: present, imperfect, perfect and pluperfect. French normally uses only two of these tenses, although Spanish and Italian and the other linguae romanae rusticae positively revel in all tense subjunctive usage. Quisiera un café, por favor. (I would like a coffee, please.)

When I was young and silly, I used to use the imperfect and pluperfect subjunctive just for laughs: J’aimerais que vous me servissiez 100 F de gasoil.

Or: Madame, réfléchîtes-vous à ma proposition car il faudrait que vous prissiez une décision immédiatement pour que je vous livrasse au plus tôt et que vous fussiez en mesure d’apprécier les services de mon appareil.

At the time I was taking a course in 18th century literature and reading people like Marivaux, Voltaire and madame de Sévigné, all of whom were comfortable with the all the subjunctives and used them in an often humorous and even schpritzy style. (Schpritzy = avec esprit.)

J’étudie la carte du Tendre, je participe aux fêtes galantes, je suis l’observateur “statufié” des tableaux de Watteau… et de Boucher.

In Latin, the past tense is called the “perfect,” because it has been thoroughly done, perfected, finished. I was = fui. You were = fuisti. It was = fuit. In spoken French this perfect past (or passé simple as it is known) is not ordinarily used in speaking, but it is in writing, especially in novels.

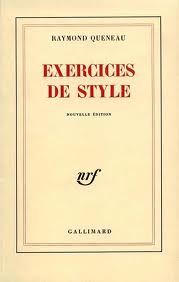

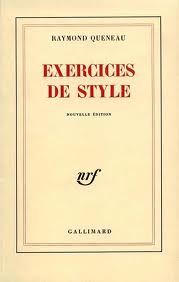

There is a French writer named Raymond Queneau. He wrote Zazie dans le métro and many other funny books that play with language.

The first book of his that I read was Exercices de Style where he takes a very simple story and tells it in many different styles: Métaphoriquement, Rétrograde, Surprises, Rêve, Pronostications, Hésitations and so on.

One of the versions of the story is Passé Simple where he uses only that tense. The usual tense for description is the imperfect, so it is strange to read all that Passé Simple.

Ce fut midi. Les voyageurs montèrent dans l’autobus. On fut serré. Un jeune monsieur porta sur sa tête un chapeau entouré d’une tresse, non d’un ruban. Il eut un long cou. Il se plaignit auprès de son voisin des heurts que celui-ci lui infligea. Dès qu’il aperçut une place libre, il se précipita vers elle et s’y assit.

Je l’aperçus plus tard devant la gare Saint-Lazare. Il se vêtit d’un pardessus et un camarade qui se trouva là lui fit cette remarque: il fallut mettre un bouton supplémentaire.

This is a wonderful book and I highly recommend it if you read French, or maybe even if you don’t read French, because it does take that simple tale and tell it over and over again in many different modes, so it is quite educational.

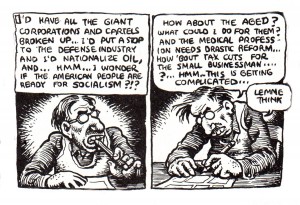

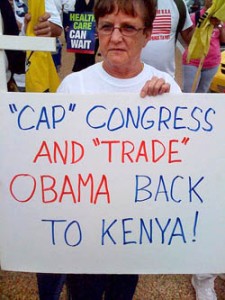

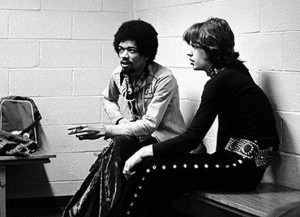

And, speaking of end, here are a couple of trous de culs américains. What they don’t know would fill a number of very large volumes.

Au revoir. À la prochaine.

____________________________________