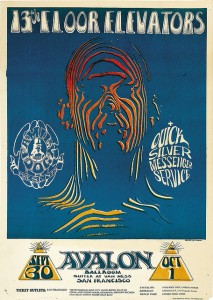

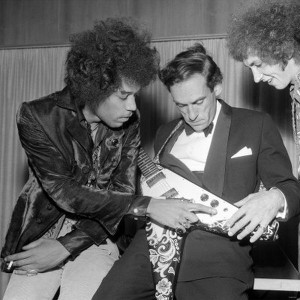

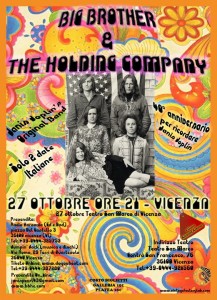

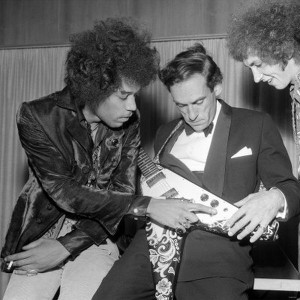

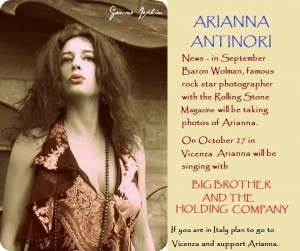

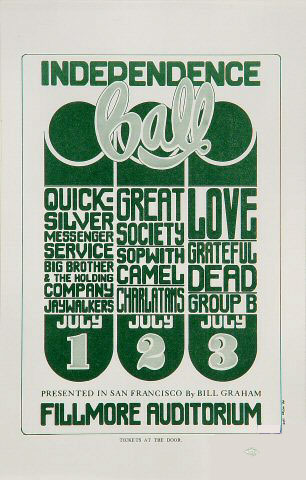

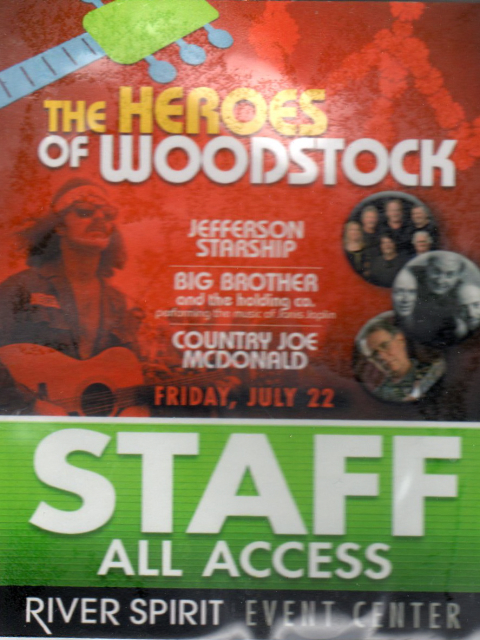

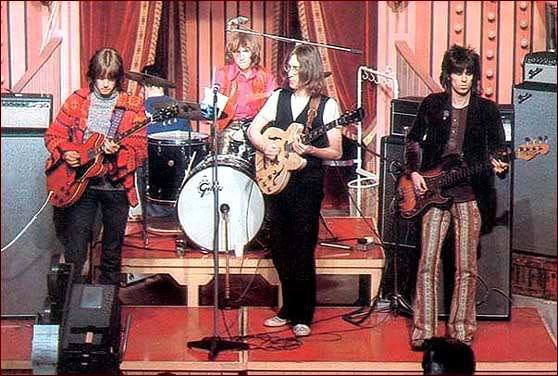

Solo il 1 febbraio è al Fillmore Auditorium

No, no, Jimi è a Winterland.

Ma noi come siamo giunti l’altra volta al 2 e al 4 febbraio? devo vedere un’altra lista di concerti….avevamo incrociato le cose e avevamo pensato che fosse possibile che quel giorno entrambi si trovassero nella stessa città in due diversi locali e che uno dei due potesse essere in visita..perchè al winterland si sono incrociati niente mi pare….o sbaglio? non ricordo più ahahhahahha

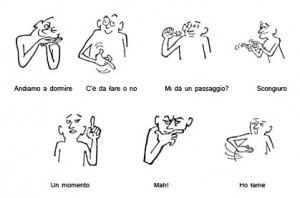

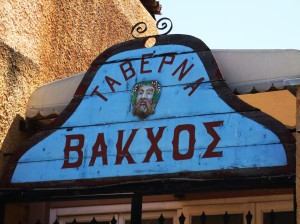

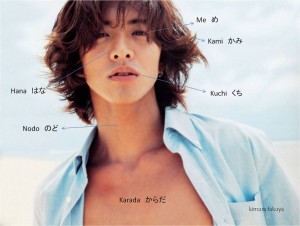

Italian is a Romance language spoken mainly in Europe in Italy, Switzerland, San Marino, Vatican City, by minorities in Malta, Monaco, Croatia, Slovenia, France, Somalia, Libya, Ethiopa and Eritrea, and by expatriate communities in the Americas and Australia. If you’ve ever stayed in Italian villas, you’ll have heard the language in all of its glory.

Voglio venire anch’io al caldo con voi.

Many of these people speak both standardized Italian and other regional languages.

Italian is spoken as a native language by 59 million people in the EU (13% of the EU population), mainly in Italy, and as a second language by 14 million (3%). English is a far more common second language. If you are trying to master your own English skills then this PTE Practice test online will be of great help to you.

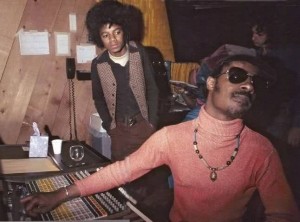

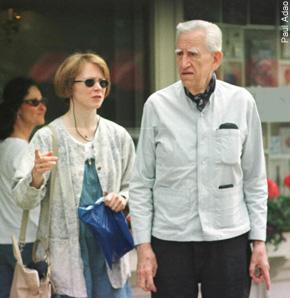

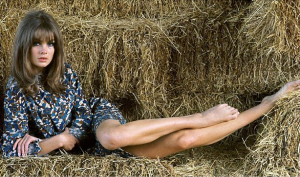

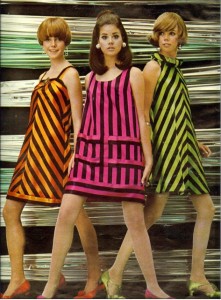

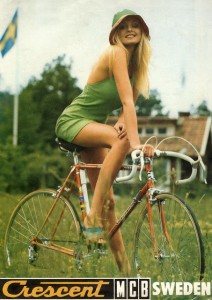

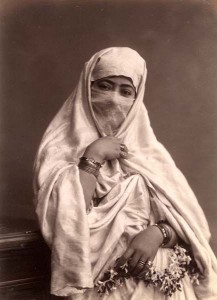

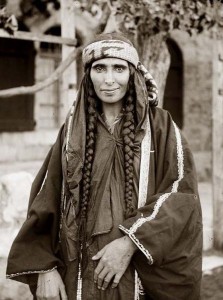

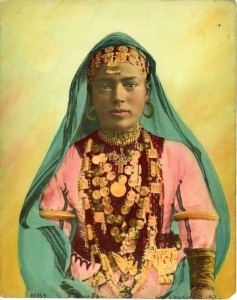

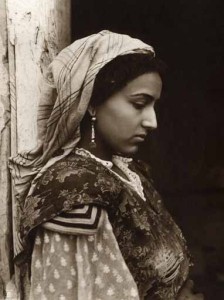

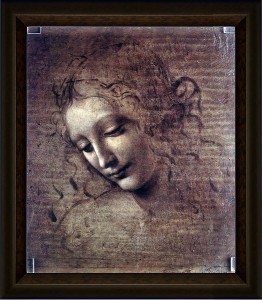

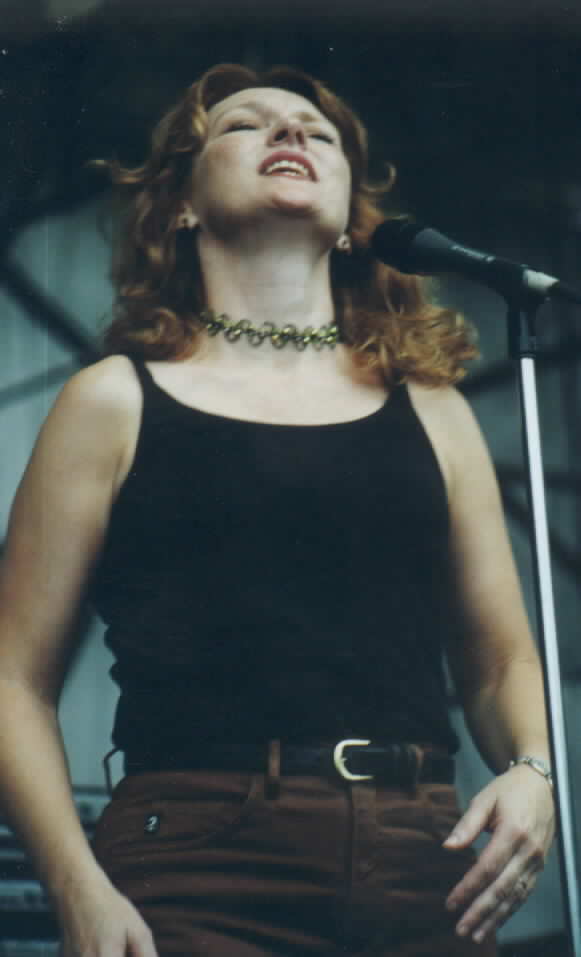

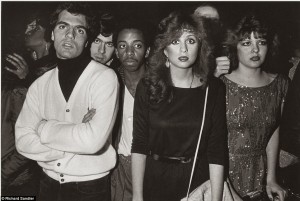

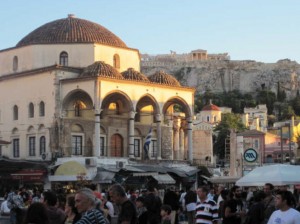

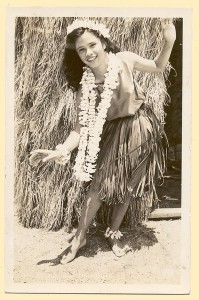

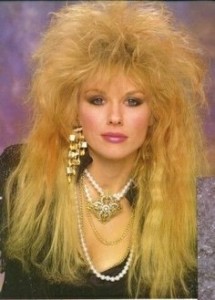

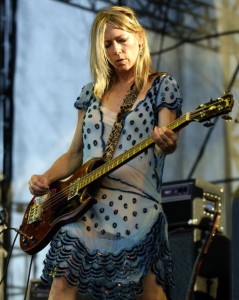

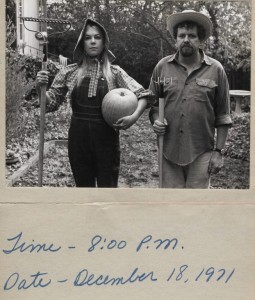

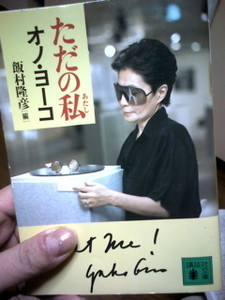

Linda foto

Including the Italian speakers in non-EU European countries (such as Switzerland and Albania) and on other continents, the total number of Italian speakers is more than 85 million.

Bellissimee! Bacionii!

In Switzerland, Italian is one of four official languages.

Italian is studied in all the confederation schools and spoken, as a native language, in the Swiss cantons of Ticino and Grigioni and by the Italian immigrants that are present in large numbers in German- and French-speaking cantons.

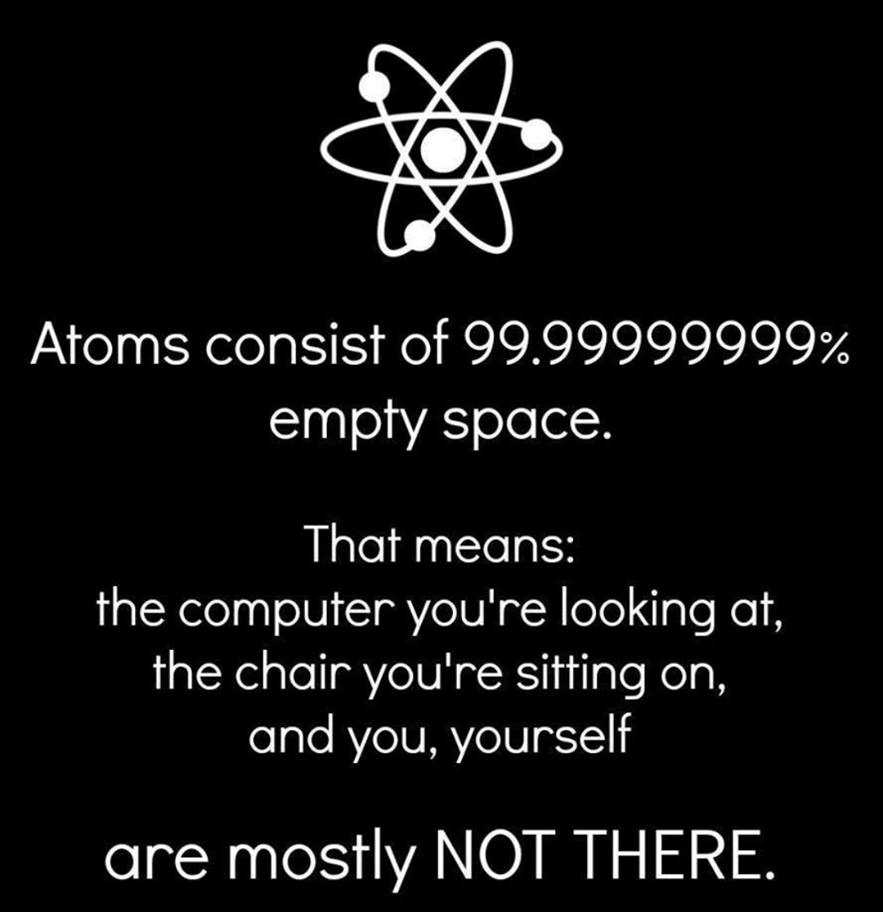

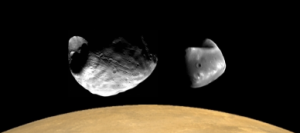

Il Sole non termina con la fotosfera e la cromosfera, ma continua in una nebulosità chiamata corona. Quest’ultima si estende oltre l’orbita di Mercurio, di Venere e della Terra…sicchè in realtà noi siamo dentro il Sole.

Italian is also the official language of San Marino, as well as the primary language of the Vatican City.

Gnoccolitudine che avanza…

Italian is co-official in Slovenian Istria and in Istria County in Croatia.

Gli occhi molto belli sono insostenibili, bisogna guardarli sempre, ci si affoga dentro, ci si perde, non si sa più dove si è.

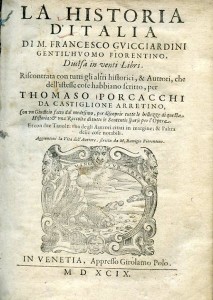

The Italian language adopted by the state after the unification of Italy in 1861 is based on Tuscan, which was a language spoken mostly by the upper class Florentine society.

The development of the national language was also influenced by other Italian dialects and by the Germanic languages of the post Roman invaders.

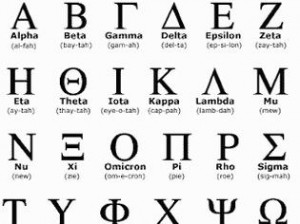

Italian is descended from Latin, and unlike most other Romance languages, retains Latin’s contrast between short and long consonants.

As in most Romance languages, stress is distinctive. Italian is the closest language to Latin in terms of vocabulary.

Italian as a language used in the Italian peninsula has a long history. The earliest surviving texts that can definitely be called Italian (or more accurately, vernacular, as distinct from its predecessor Vulgar Latin) are legal formulae from the province of Benevento that date from 960–963.

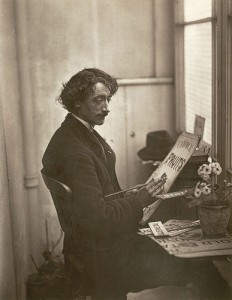

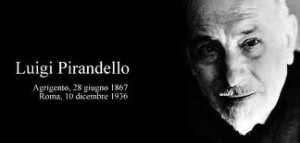

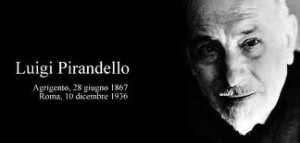

What would come to be thought of as Italian was first formalized in the early fourteenth century through the works of Tuscan writer Dante Alighieri, written in his native Florentine.

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita,

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,

ché la diritta via era smarrita.

Dante’s epic poems, known collectively as the Commedia, which another Tuscan poet Giovanni Bocaccio called Divina, were read throughout Italy and his written dialect became the “canonical standard” that all educated Italians could understand.

Dante is still credited with standardizing the Italian language, and thus the dialect of Florence (Tuscan, toscano) became the basis for what would become the official language of Italy.

Italian often was an official language of the various Italian states preceding the nineteenth century unification, slowly usurping Latin, even when the country was ruled by foreign powers such as the Spanish in Naples or the Austrians in the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia.

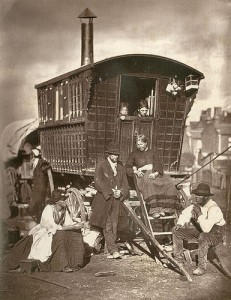

The great mass of people in the peninsula spoke primarily vernacular languages and dialects.

Italian was also one of the many recognized languages in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Italy has always had a distinctive dialect for each city, because the cities, until recently, were thought of as separate countries, as city-states.

The regional dialects of Italy have always had great variety, and many/most of them are mutually incomprehensible.

As Tuscan-derived Italian came to be used throughout Italy, features of local speech were naturally adopted, producing various versions of Regional Italian.

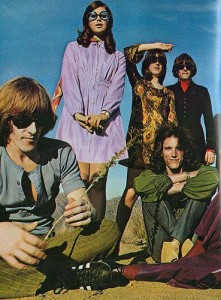

Tanti bei ricordi.

The most characteristic differences, for instance, between Roman Italian and Milanese Italian are the gemination (‘twinning’) of initial consonants and the pronunciation of stressed “e”, and of “s” in some cases. Va bene ”all right” is pronounced [va ?b??ne] by a Roman (and by any standard-speaker), [va ?bene] by a Milanese (and by any speaker whose native dialect lies to the north of La Spezia-Rimini Line.

A casa ”at home” is [a ?k?asa] for Roman and standard, [a ?kaza] for Milanese and generally northern regions.

In contrast to the northern Italian, southern Italian dialects and languages were largely untouched by the Franco-Occitan influences introduced to Italy, mainly by bards and trouvères (troubadours) from France during the Middle Ages.

After the Norman conquest of southern Italy, Sicily became the first Italian land to adopt Occitan lyric moods (and words) in poetry.

Scholars are careful not to overstate the effects of outsiders on the natural indigenous developments of the languages even in the case of northern Italian.

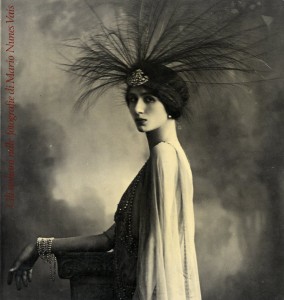

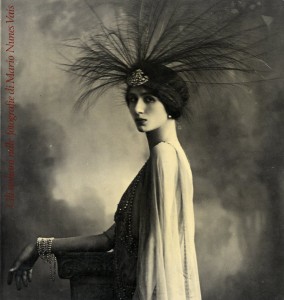

Ho conosciuto l’amore, in tutte le sue vivaci forme d’espressione… E non mi sono mai meravigliata di niente!

The economic might and relatively advanced development of Tuscany in the late middle ages gave that dialect weight, although the Venetian language remained widespread in medieval Italian commercial life.

Dobbiamo festeggiare , bacione stellina …auguri.

Ligurian or Genoese remained in use in maritime trade alongside the Mediterranean, but the increasing political and cultural relevance of Florence during the periods of the rise of the Medici’s financial power, the currents of Humanism and the Renaissance made the Florentine dialect, or rather a refined version of it, a standard in the arts.

Ne avevo pure un’altra ma non ricordo dove.

From the Renaissance on, Italian became the language used in the courts of every state in the peninsula.

Le tre ave maria !

The rediscovery of Dante’s De vulgari eloquentia and a renewed interest in linguistics in the sixteenth century, sparked a debate that raged throughout Italy concerning the criteria that should govern the establishment of a modern Italian literary and spoken language.

Posso rubare questa foto?

Scholars divided into three factions:

- The purists, headed by Venetian Pietro Bembo (who, in his Gli Asolani, claimed the language might be based only on the great literary classics, such as Petrarca and some part of Boccaccio). The purists thought the Divine Comedy not dignified enough, because it used elements from non-lyric registers of the language.

- Niccolò Machiavelli and other Florentines preferred the version spoken by ordinary people in their own times.

- The courtiers, like Baldassare Castiglione and Gian Giorgio Trissino, insisted that each local vernacular contribute to the new standard.

- A fourth faction claimed that the best Italian was the one that the papal court adopted, which was a mix of Florentine and the dialect of Rome.

- Eventually, Bembo’s ideas prevailed, and the foundation of the Accademia della Crusca in Florence (1582–1583), the official legislative body of the Italian language, led to publication of Agnolo Monosini’s Latin work Floris italicae linguae libri novem in 1604 followed by the first Italian dictionary in 1612.

An important event that helped the diffusion of Italian was the conquest and occupation of Italy by Napoleone in the early nineteenth century (who was himself of Italian-Corsican descent).

This Napoleonic conquest propelled the unification of Italy some decades after, and turned Tuscan Italian into a lingua franca used not only by clerks, nobility and functionaries in the Italian courts but also by the bourgeoisie.

In Italian literature’s first modern novel, I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed), Alessandro Manzoni further defined the standard language by “rinsing” his Milanese dialect “in the waters of the Arno” (Florence’s river), as he stated in the Preface to his 1840 edition.

After unification a huge number of civil servants and soldiers recruited from all over the country introduced many more words and idioms from their home languages.

“Ciao,” for example, is derived from a Venetian word “s-cia[v]o” (slave), meaning ‘I am your slave,” a phrase of affection. Click the link to learn more Greetings in Italian.

“Panettone” (a kind of Christmas cake) comes from the Lombard word “panatton.”

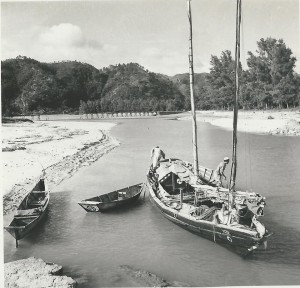

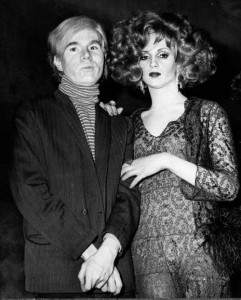

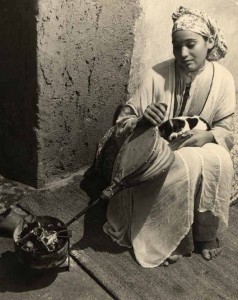

Una foto da non perdere.

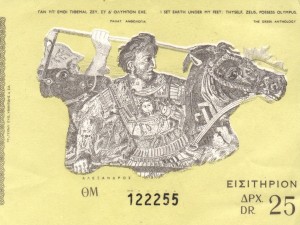

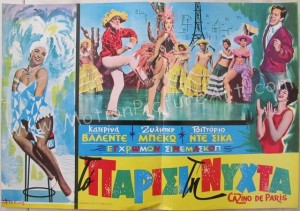

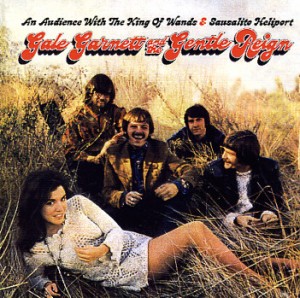

Caterina Russo

Caterina Russo

Only 2.5% of Italy’s population could speak the Italian standardized language properly when the nation unified in 1861. Eighteen sixty-one. The USA, always touted as a ‘new’ nation, was almost a hundred years old by this time.

Italian is part of the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family, and is related most closely to the other two Italo-Dalmatian languages, Sicilian and the extinct Dalmatian.

Belli tutti, ma l’acchiappasogni…

Italian lexical similarity to Latin is 90%.

French is 88%. Catalan 85%, with Sardinian 82%, with Spanish and Portuguese 78%, with Rhaeto-Romance and Romanian 77%.

A gnocca!

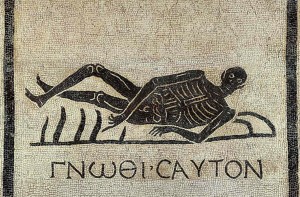

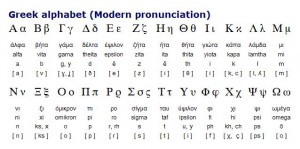

Knowledge of Italian according to EU statistics

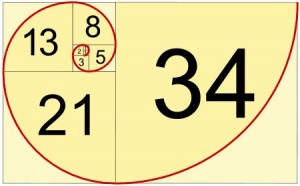

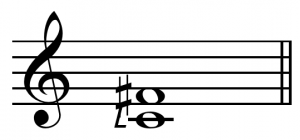

Sei un bel fiore. Ti chiami il Fibonacci.

Ti sembro una che se le deve far spiegare le cose?

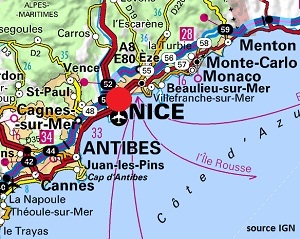

Italian is spoken by a minority in Monaco and France (especially in the southeast of the country and Corsica).

Small Italian-speaking minorities can also be found in Albania and Montenegro.

Ti ho taggato perchè Ezio mi aveva accennato della tua passione per le gocce!

Due to heavy Italian influence during the Italian colonial period, Italian is still widely understood in the countries of Libya and Eritrea.

Although it was the primary language of Libya under colonial rule, Italian greatly declined under the rule of Muammar Gaddafi, who expelled the Italian Libyan population and made Arabic the sole official language of the country.

Ragazzi è stato un piacere e un onore conoscervi.. addioooooooooooo!

Italian remains an important language in the education and economic sectors in Libya.

In Eritrea, Italian is a principal language in commerce and the capital city Asmara still has an Italian-language school.

Italian was also introduced in Somalia through colonialism and was the sole official language of administration and education during the colonial period but declined after government, educational and economic infrastructure was destroyed in the Somali Civil War.

Italian was also used in administration in Ethiopia when the country was briefly occupied by Italy from 1936 to 1941.

Although over 17 million Americans are of Italian descent, only a little over one million people in the United States speak Italian at home, but an Italian language media market does exist in the US.

In Canada, Italian is the second most spoken non-official language when Chinese dialects are not combined, with over 660,000 speakers (or about 2.1% of the population) according to the 2006 Census.

Si qualunque contatto reale è pù importante di altri virtuali, ciao Anthea, grazie e buona serata !

In Australia, Italian is the second most spoken foreign language after the Chinese languages, with 1.4% of the population speaking it as their home language.

Italian immigrants to South America have also brought a presence of the language to the continent.

Italian is the second most spoken language in Argentina after the official language of Spanish, with 1.5 million speaking it natively, and Italian has also heavily influenced the dialect of Spanish spoken in Argentina and Uruguay,which is called Rioplatense Spanish (from Rio Plata).

Siamo i migliori.

Small Italian-speaking minorities on the continent are also found in Uruguay, Venezuela and Brazil.

Italian is widely taught in many schools around the world, but rarely as the first foreign language. Italian is considered the fourth- or fifth-most frequently taught foreign language in the world.

According to the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, every year there are more than 200,000 foreign students that are learning Italian language, distributed in the 90 Institutes of Italian Culture in the world, in the 179 Italian schools abroad and in the 111 Italian sections that are open into foreign schools.

In the United States, Italian is the fourth most taught foreign language after Spanish, French and German, in that order (or the fifth if American Sign Language is considered).

In central-eastern Europe Italian is first in Albania and Montenegro, second in Austria, Croatia, Slovenia, and Ukraine after English, and third in Hungary, Romania and Russia after English and German.

Throughout the world, Italian is the fifth most taught foreign language, after English, French, German, and Spanish.

Italian is spoken as a native language by 13% of the European Union population, or 65 million people, mainly in Italy.

In the European Union, Italian is spoken as a second language by 3% of the EU population, or 14 million people.

In addition, among EU states, the Italian language is most likely to be learned as a second language in Malta by 61% of the population,

as well as in Slovenia by 15% of the population,

in Croatia by 14% of the population,

in Austria by 11% of the population,

Romania by 8% of the population, and in France and Greece by 6% of the population.

Italian is also one of the national languages of Switzerland, which is not a part of the European Union.

The Italian language is well-known and studied in Albania, another non-EU member, due to its historical ties and geographical proximity to Italy.

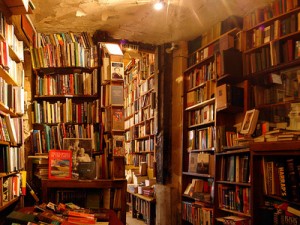

During the Renaissance, Italy held artistic sway over the rest of Europe. All educated European gentlemen were expected to make the Grand Tour, visiting Italy to see its great historical monuments and works of art. It thus became expected that educated Europeans should learn at least some Italian.

During the Elizabethan period, especially, there was a strong Italian influence on English cultural life. Think of all the Italian plots in Shakespeare.

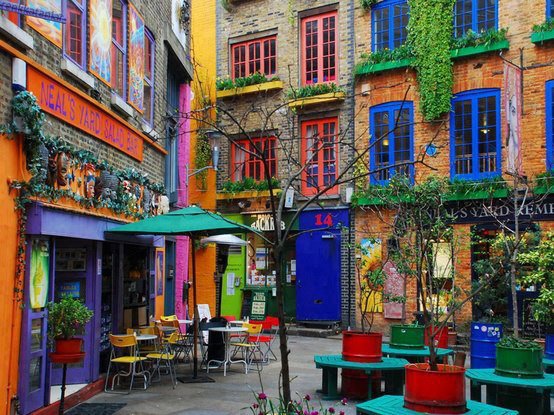

Vedi che non si sta poi così male a Malta!

In Florence, which I have always admired above all others because of the elegance, not just of its tongue, but also of its wit, I lingered for about two months. There I at once became the friend of many gentlemen eminent in rank and learning, whose private academies I frequented — a Florentine institution which deserves great praise not only for promoting humane studies but also for encouraging friendly intercourse. John Milton Defensio Secunda

In England, Italian became the second most common modern language to be learned, after French (though the classical languages, Latin and Greek, came first).

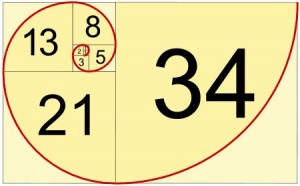

In the Catholic Church, of course, Italian is known by a large part of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, and is used in substitution for Latin in some official documents.

I was raised as a Catholic from birth, so these languages, Italian and Latin were second languages for me, because I served mass (which was in Latin then) from a very early age.

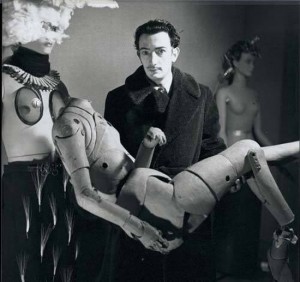

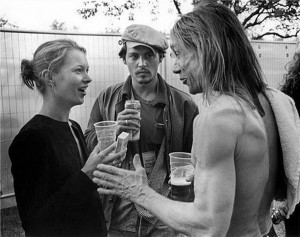

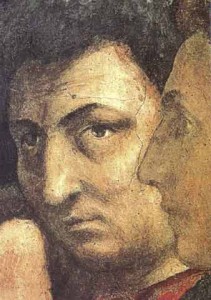

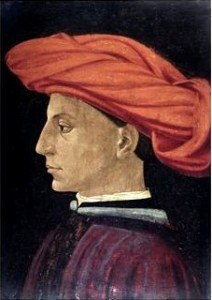

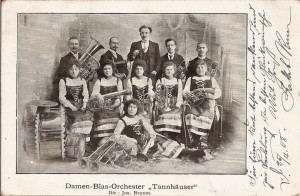

Un capolavoro

Un capolavoro

I liked Latin and Italian, because they are musical and sonorous.

Part of the beauty of these languages is that they follow every consonant with a vowel, so that the language sings.

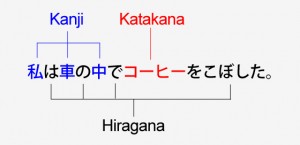

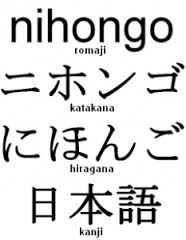

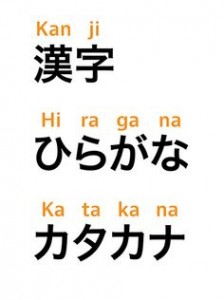

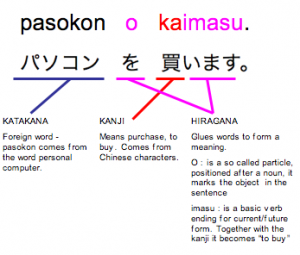

There are other consonant vowel languages, though (Japanese comes to mind), and they don’t quite sing the way Italian does.

The presence of Italian as the primary language in the Vatican indicates use, not only within the Holy See, but also throughout the world where an episcopal seat is present.

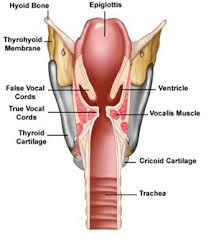

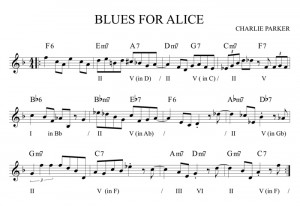

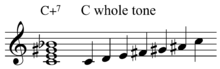

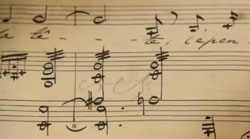

Italian is the principal language, of course, in music and opera.

Throughout Italy, regional variations of Standard Italian, called Regional Italian are spoken.

In Italy, almost all Romance languages spoken as the vernacular, other than standard Italian and distantly-related, non-Romance languages spoken in border regions or among immigrant communities, are often imprecisely called “Italian dialects,” even though they are quite different, with some belonging to different branches of the Romance language family.

The only exceptions to this are Sardinian, Ladin and Friulan, which the law recognizes as official regional languages.

The Corsican language is also related to Italian.

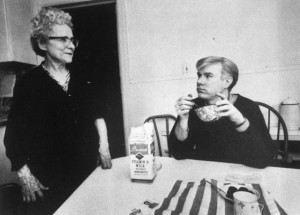

La nonnina…carina.

Regional differences can be recognized by various factors: the openness of vowels, the length of the consonants, and influence of the local language (for example, in informal situations the contraction annà replaces andare in the area of Rome for the infinitive “to go”; and nare is what Venetians say for the infinitive “to go”).

In Italian, as in most Romance languages and even English, cases exist for pronouns (nominative, oblique, accusative and dative) but not for nouns.

There are two genders (masculine and feminine).

Nouns, adjectives, and articles inflect for gender and number (singular and plural).

Adjectives are sometimes placed before their noun and sometimes after. For an English speaking person, this is a very confusing area in Italian, French, Spanish, Portugues and the rest.

Adjectives usually come after the noun in Italian. Adjectives can be feminine or masculine, singular or plural, depending on the gender and number of the noun to which they refer. La folla felice The happy crowd

In English, we almost always put the adjective before the noun (she’s a good woman), but in Italian, eh?, there are some guidelines but practice and hearing a native, as always, are best. Generally speaking, if the adjective is short and very common, it can go before the noun, but these have to be learned on a case by case basis.

Subject nouns generally come before the verb. Subjective pronouns are usually dropped, their presence implied by verbal inflections.

Siete belle e giovane!

Noun objects come after the verb, as do pronoun objects after imperative verbs and infinitives, but otherwise pronoun objects come before the verb.

There are numerous contractions of prepositions with subsequent articles, maybe more than in any other daughter of Latin. Della, della, nello, nella, colla, collo and on and on.

There are numerous productive suffixes for diminutive, augmentative, pejorative, attenuating and the like, which are also used to create nelogisms. Maybe Italian is richer in these, too, than any of her sisters.

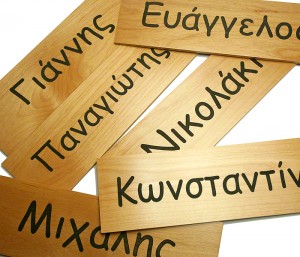

Many names in Italian began as the endings of longer, more ‘proper’ names.

The artist Masaccio? He was born Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone 1421-1428 CE. Then his name Tommasso was shortened to Maso, and then a big, ugly augmentive ending was appended, so he became Masaccio, the only name we know him by. Big old Tom.

His principal collaborator was another Tom, another Maso, but this man was called Masolino, the opposite of Masaccio. Little, delicate, sprightly Tom. Big, ugly Tom did all of the paintings. That was his revenge.

In Italian, there are three regular sets of verbal conjugations, and various verbs are irregularly conjugated.

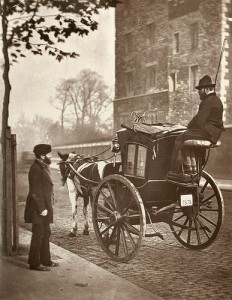

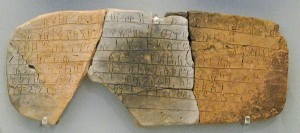

The most ancient text in a ‘langue romane’ is a veronese riddle. It reads like this

Se pareba boves (they rounded up their cattle)

alba pralia araba (they were plowing on a white field)

albo versorio tenebra (they had a white plow)

negro semen seminaba (they sowed black seed)

The solution: This is about the hand that is writing, because… the boves (oxen) are the fingers, the white field is the parchment, the fingers had a white plow (the goose quill) and the black seed is the ink going on to the parchment.

OK, this riddle is not deathless humor, but it is the first thing written in the vernacular in Italian (as opposed to Vulgar Latin).

Tu e tua figlia

A dialect isn’t somehow inferior to a language. A dialect is a language. Italian, Spanish and French are languages because they have acquired a prestige in becoming literary languages and they are official languages of state, but Sicilian, Neapolitan, Picard, Tuscan, Friulian, these dialects are all languages too.

Articolo determinativo (definite article)

lo: for masculine singular nouns beginning with z or s+consonant Lo schiavo.

The plural is gli. Lo specchietto retrovisore rear view mirror

Il: for masculine singular nouns beginning with all other consonants

plural=i Ma sei sempre in giro per il mondo? Are you still touring the world?

l’: for masculine singular nouns beginning with any vowel

plural=gli l’anatroccolo brutto the ugly duckling

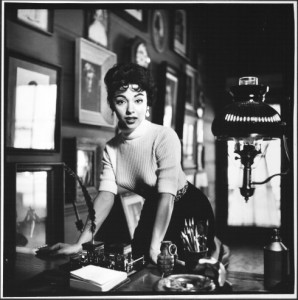

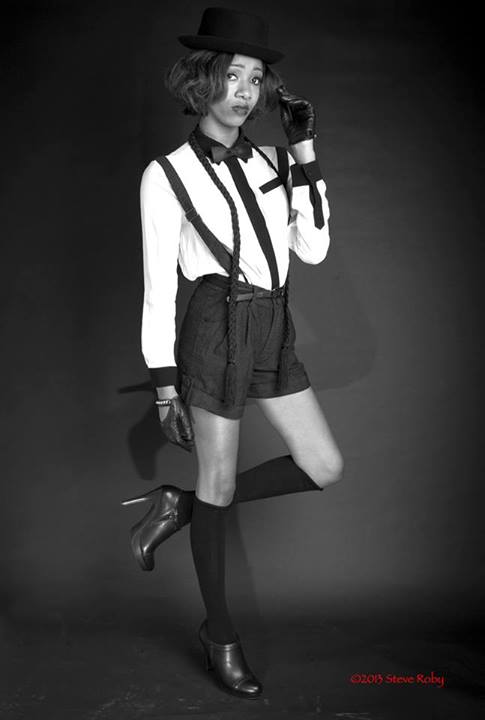

La classe , la raffinatezza..Superlativa Billie Holiday.

La classe , la raffinatezza..Superlativa Billie Holiday.

la: for feminine singular nouns beginning with any consonant

plural=le

l’: for feminine singular, beginning with any vowel

plural=le L’amica del cuore

articolo indeterminativo (indefinite article; singular only)

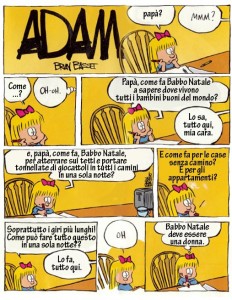

una: for feminine nouns beginning with any consonant una donna

un’: for feminine nouns beginning with any vowel un’antologia

uno: for masculine nouns beginning with z or s+consonant Uno scherzo A joke

un: for all other masculine nouns Giorgio è sempre Giorgio. È un musicista.

Adjectives that end in “a” are usually feminine and form the plural with “e.” La coppia capricciosa The capricious couple

Adjectives that end in “o” are masculine and form the plural with “i.” Come mi disse una volta mia madre, Pa stai impazzendo!

Adjectives that end in “e” can be masculine or feminine and in either case form the plural with “i.” Janis in questa foto è davvero dolce, è dolcissima.

Adjectives that end in “ista” can be masculine or feminine, and they form the plural in the regular way–with “i” if masculine, with “e” if feminine: L’artista è un uomo.

The adjectives of color beige, blu, rosa, and viola are invariable. They stay the same wherever they are.

Certain common short adjectives normally precede the noun: bello, brutto, buono, cattivo, giovane, grande, nuovo, piccolo, vecchio.

The adjective “buono” follows the pattern of the indefininite articles un artista>>un buon artista

uno zaino>>un buono zaino

uno specchio>>un buono specchio

una artista>>una buona artista

un’amica>>una buon’amica

The adjectives “quello” and “bello” follow the pattern of the definite articles l’uomo>>un bell’uomo/quell’uomo

lo scherzo>>un bello scherzo/quello scherzo

l’amante>>un bell’amante/quell’amante

gli animali>>dei begli animali/quegli animali

gli studenti>>dei begli studenti/quegli studenti

gli amici>>dei begli amici/quegli amici

la Veronica>>la bella Veronica/quella Veronica

l’amica>>la bell’amica/quell’amica

le donne>>le belle donne/quelle donne

le ampolle>>le belle ampolle/quelle ampolle (cruets)

There are three classes, or conjugations, of verbs in Italian, according to the last three letters of their infinitive: ”-are,” “-ere,” and “-ire”

A few infinitives end in –rre, such as trarre, porre, and derivatives.

Dovresti essere fiero dei colori della mia maglia! You should be proud of the colors on my jersey!

Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs. They do not agree with the word which they modify.

Many adverbs are formed by adding the suffix “-mente” to the feminine singular form of the adjective. Ciao Veronica finalmente vedo il tuo visino!

Smettila di sfottere!

veloce>>velocemente; lento>>lentamente

bene=well male=badly molto=very poco=little troppo=too, too much

Lei è una donna molto brava: studia sempre!

L’Espagna è troppo lontana, vorrei andarci più spesso.

IL COMPARATIVO: There are three comparatives: di maggioranza (more than), di minoranza (less than), di uguaglianza (the same)

comparativo di maggioranza più…di più…che I supermercati americani sono più grandi che belli.

comparativo di minoranza meno…di meno…che Gli italiani bevono meno degli americani.

Use “DI“: 1.when two terms are compared with respect to one quality/action 2.in front of numbers

you use “CHE” Gli americani bevono meno cappuccino che caffé.

3.when there is one term and two qualities/actions refer to this one term

4.in front of a preposition

5.in front of an infinitive

comparativo di uguaglianza the same as Coca-Cola is as popular as it is deficient in nutritive value.

a. (così)…come or (tanto)…quanto La Coca-Cola è (tanto) popolare quanto priva di valore nutritivo.

(for adjective and adverbs: “così…come” and “tanto…quanto” are adverbs and there is no agreement)

b. (tanto)…quanto

(for nouns: here “tanto…quanto” are adjectives and there is agreement) Gli americani mangiano tanti popcorn quante patatine.

c. (tanto) quanto…

(for verbs: “(tanto)…quanto” are adverbs and there is no agreement) Gli americani bevono (tanto) quanto gli italiani.

così and tanto are optional and usually avoided

II. IL SUPERLATIVO RELATIVO The relative superlative is formed by:

the definite article (il, la, i , le) + (noun) + più/meno + adjective + di + the term in relation to which we are comparing

Le confezioni itliane sono le più grandi del mondo.

III. SUPERLATIVO ASSOLUTO is the equivalent of the English “very+adjective” and “adjective+est” or “most+adjective.” In Italian this can be expressed in several ways:

1. by adding -issimo/a/i/e at the end of an adjective I supermercati americani sono grandissimi.

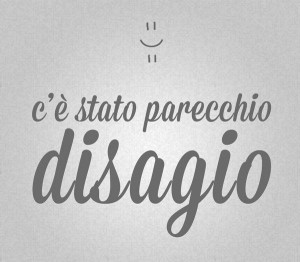

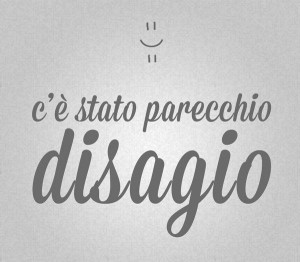

2. by placing molto, tanto, parecchio, assai in front of the adjective C’è stato parecchio disagio. It was very uncomfortable.

3. by using the prefix arci-, stra-, super-, ultra- L’espresso è arcipopolare. Il cappuccino è superchic.

4. by using stock phrases such as ricco sfondato (filthy rich); ubriaco fradicio (very drunk); stanco morto (dead tired); bagnato fradicio (soaking wet); innamorato cotto (madly in love)…

5. by repeating the adjective or the adverb

6. some adjectives have irregular superlatives: acre/acerrimo; celebre/celeberrimo; integro/integerrimo; celebre/celeberrimo; misero/miserrimo; salubre/saluberrimo; in spoken language, however, people just avoid “-issimo” with these and use “molto, tanto, parecchio, assai.”

III. COMPARATIVI E SUPERLATIVI IRREGOLARI the comparative of “bene” is always “meglio“

the comparative of “buono” can be “migliore” (“più buono” can also be used)

the comparative of “male” is always “peggio“

the comparative of “cattivo” can be “peggiore” (“più cattivo” can also be used)

“maggiore” is an alternative to “più grande” (più grande=bigger maggiore=greater)

“minore” is an alternative to “più piccolo” (più piccolo=smaller minore=lesser)

Conjunctions join words and sentences together. Some conjunctions, longer ones, require the use of the subjunctive. They are:

benché, sebbene, malgrado, nonostante, quantunque (all mean: although, in spite of, even though)

purché, a patto che, a condizione che (all mean: provided that)

nel caso che (in case)

Some others require the use of the subjunctive only if the subject of the main verb and the subject of the subjunctive are different; if the subjects are the same, the infinitive is required. They are:

affinché, perché, cosicché, in modo che (in order to, so that)

senza che (without)

prima che (before)

Personal pronouns

|

First Person |

Second Person |

Third Person |

| Singular |

Plural |

Singular |

Plural |

Reflexive |

Masculine |

Feminine |

| Singular |

Plural |

Singular |

Plural |

| Subject |

io |

noi |

tu |

voi |

– |

egli, esso (lui) |

essi (loro) |

ella, essa (lei) |

esse (loro) |

| Stressed Object |

me |

noi |

te |

voi |

sé |

lui |

loro |

lei |

loro |

| Clitic accusative |

mi |

ci |

ti |

vi |

si |

lo |

li |

la |

le |

| Clitic dative |

mi |

ci |

ti |

vi |

si |

gli |

gli,loro |

le |

gli,loro |

| Clitic dat. before acc. |

me |

ce |

te |

ve |

se |

glie- |

glie- |

glie- |

glie- |

Second person nominative pronoun is tu for informal. For formal use, the 3rd person form Lei has been used since the Renaissance. Lei is used like “Sie” in German, “Usted” in Spanish and “você” in Portuguese.

Previously, and in some Italian regions today (Campania), voi is used as a formal singular, as in the French “vous”. The pronouns lei (third-person singular) and Lei (second-person singular formal) are pronounced the same but written as shown. Formal Lei and Loro take third-person conjugations. Lei was originally an object form of ella, which in turn referred to an honorific of the feminine gender such as la magnificenza tua / vostra (“Your Magnificence”) or Vossignoria (“Your Lordship”).

These are hard times for someone who opens her heart and not her legs.

These are hard times for someone who opens her heart and not her legs.

Accusative lo and la elide to l’ before a vowel or before h: l’avevo detto (“I had said it”), l’ho detto (“I have said it”).

When accusative pronouns are used in a compound tense, the final vowel of the past participle must agree in gender and number with the accusative pronoun. For example, hai comprato i cocomeri e le mele? (“Did you buy the watermelons and the apples?”) –Li [i cocomeri] ho comprati ma non le [le mele] ho comprate (“I bought them [the former] but I did not buy them [the latter]“). This also happens when the underlying pronoun is made opaque by elision: l’ho svegliato (“I woke him up”), versus L’ho svegliata (“I woke her up”).

In modern Italian, dative gli (to him) is used commonly even as plural (to them) instead of classical loro. So: “Conosci Luca: gli ho sempre detto di stare lontano dalle cattive compagnie” (You know Luca: I have always told him to stay away from bad company.”). And: “Conosci Luca e Gino: gli ho sempre detto…” (…I have always told them…) instead of “… ho sempre detto loro di stare…”.

Though objects come after the verb as a rule, this is not the case with a class of unstressed, clitic pro-forms.

Dative and accusative pronouns come before the verb. If an auxiliary verb is used, the pronouns come before the auxiliary. If both dative and accusative pronouns are used, the dative comes first. Pronominal particles ce/ci (to it) and ne (of it) are treated like accusative pronouns for word-order purposes.

Note that the clitic ci acts both as a first person plural accusative pronoun and a pro-form with a different meaning.

Davide lascia la sua penna in ufficio. David leaves his pen at the office.

Davide la lascia in ufficio. David leaves it at the office.

Davide ce la lascia. David leaves it with us.

copyright Daniela Rettore

copyright Daniela Rettore

Davide ce ne lascia una. David leaves us one of them.

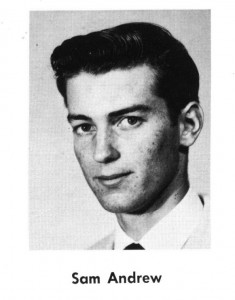

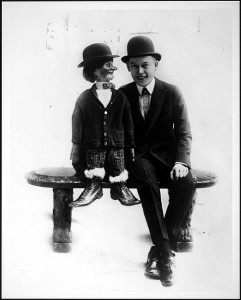

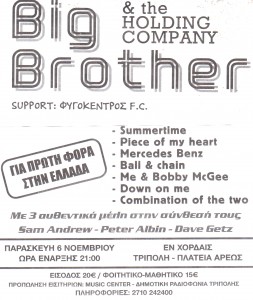

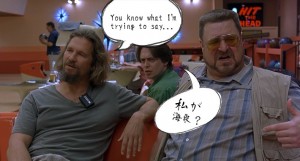

Certo, la faccia sconsolata di Sam dice tutto.

Davide potrebbe lasciarcene una. David might leave us one of them. Or, could leave us one of them.

In the imperative and subjunctive moods, the objective pronouns come once again after the verb, but this time as a suffix.

Davide lascia la sua penna in ufficio. David leaves his pen in the office.

“Lasciala in ufficio.” ”Leave it at the office.”

“Lasciacela.” ”Leave it to us.”

Davide potrebbe lasciarla in ufficio. David could leave it at the office.

Non lasciarcela. Don’t leave it to us. Don’t leave it with us.

Davide dovrebbe lasciarcela. David should leave it with us.

Dative mi, ti, ci, and vi become me, te, ce, and ve when preceding another pronoun (“dammelo” (give it to me) or develop as a me, a te, a noi and a voi when emphasized (“dallo a me” (give it TO ME).

Accusative mi, ti, lo, la, ci, and vi become me, te, lui, lei, noi, and voi when emphasized (“uccidimi” (kill me) against “uccidi me, non lui” (kill me, not him).

Dative gli, le, loro (commonly gli) can be developed into a lui, a lei, a loro, when emphasized (“lo sai solo tu: a loro non l’ho detto” (only you know it: I have not told them))

Dative gli combines with accusative lo, la, li, le and ne (partitive, meaning “of it” or “of them”) to form glielo, gliela, glieli, gliele and gliene. These combinations are used for feminine and plural too (“Maria lo sa? Gliel’hai detto?” (Does Maria know it? Have you said it to her?)).

She’s too polite to say, “Gli italiani lo fanno meglio.” (Italians do it better.)

As I mentioned before, the Italian infinito presente may end by one of these three endings, either -are, -ere, or -ire. Exceptions are also possible fare ”to do/make” (from Latin facere), and verbs ending in -urre or -arre, most notably tradurre (Latin traducere) “to translate”.

Italian grammar does not have distinct forms to indicate specifically verbal aspect, though different verbal inflections and periphrases do render different aspects in particular the perfective and imperfective aspects and the perfect tense–aspect combination.

While the various inflected verbal forms convey a combinaton of tense (location in time), aspect, and mood, language-specific discussions generally refer to these inflectional forms as “tempi.” Thus it is impossible to make comparisons between the tenses of English verbs and the tempi of Italian verbs as there is no correspondence at all.

| Tense |

Italian name |

Example |

English equivalent |

| Indicative Mood |

| Present |

indicativo presente |

faccio |

I do

I am doing[verbs 1] |

| Imperfect |

indicativo imperfetto |

facevo |

I did/used to do

I was doing[verbs 2] |

| Future |

futuro semplice |

farò |

I will do |

| Preterite |

passato remoto |

feci |

I did (historic)[verbs 3] |

| Conditional mood |

| Present |

condizionale presente |

farei |

I would do |

| Subjunctive mood |

| Present |

congiuntivo presente |

(che) io faccia |

(that) I do |

| Imperfect |

congiuntivo imperfetto |

(che) io facessi |

(that) I did/do |

| Imperative mood |

| Present |

imperativo |

fa’/fai! |

do! (sing. informal) |

These are simple verb tenses.

Smettilaaaaaaaaa, ti prego.

Below are the compound tenses:

| Tense |

Italian name |

Example |

English equivalent |

| Indicative Mood |

| Recent past |

passato prossimo |

ho fatto |

I have done

I did[verbs 4] |

| Recent pluperfect |

trapassato prossimo |

avevo fatto |

I had done[verbs 5] |

| Future perfect |

futuro anteriore |

avrò fatto |

I will have done |

| Remote pluperfect |

trapassato remoto |

ebbi fatto |

I had done[verbs 5] |

| Conditional mood |

| Preterite |

condizionale passato |

avrei fatto |

I would have done |

| Subjunctive mood |

| Preterite |

congiuntivo passato |

(che) io abbia fatto |

(that) I did |

| Pluperfect |

congiuntivo trapassato |

(che) io avessi fatto |

(that) I had done |

Impersonal verb forms:

| Tense |

Italian name |

Example |

English equivalent |

| Infinitive |

| Present |

infinito presente |

fare |

to do |

| Past |

infinito passato |

aver fatto |

to have done |

| Gerund |

| Present |

gerundio presente |

facendo |

doing |

| Past |

gerundio passato |

avendo fatto |

having done |

| Participle |

| Present |

participio presente |

facente |

doing |

| Past |

participio passato |

fatto |

done |

Present tense, indicative mood, progressive aspect: io sto facendo ( I’m doing)

Present tense, indicative mood, inchoative aspect: io sto per fare (I’m about to do)

Oooohhh, che belliniiiii.

The simple preterite is becoming obsolete in spoken Italian (as in French and High German).

In ordinary conversation, one uses instead, the present perfect. Ho fatto not feci. I have done not I did.

The preterite (in some languages called the simple past) is still used in Southern Italy but is becoming less common there, too.

The preterite is, however, very common in literature, even modern literature. This is the same in French.

If there is no reference to the present, as when speaking of the dead, the simple preterite must be used.

Che gnocca.

In Italian, compound tenses are formed with an auxiliary verb (either essere ”to be” or avere ”to have”).

Transitive verbs use avere as their auxiliary verb. Verbs in the passive voice use essere or venire, with a different meaning. la porta è stata aperta, the door has been opened. La porta viene aperta, the door is being opened.

For intransitive verbs a useful rule of thumb is that if a verb’s past participle have adjectival value, essere is used, otherwise use avere.

Also, reflexive verbs and unaccusative verbs use essere (typically non-agentive verbs of motion and change of state, such as, involuntary actions like cadere (to fall) or morire (to die)). This is the same in French. We learned it as verbs of motion use essere (être) in compound tenses.

In French and Italian, the distinction between the two auxiliary verbs is important for the correct formation of the compound tenses and is essential to the agreement of the past participle. Some verbs use both avere and essere (such as vivere to live). In recent past tense you can say io ho vissuto or io sono vissuto (I have lived).

Magnifica come sempre.

It is probably necessary to repeat here, an eternal truth of language learning: The best, absolutely best way to learn Italian is to come out of an Italian mother’s womb and live with her for seven years or so.

The next best way to learn Italian is to live in Italy for ten years and learn, learn, learn.

Any other way to learn Italian, besides total immersion, will never get you quite there. Every linguist knows this, BUT we can’t all have la mamma and we can’t all live there for ten years, so this is how we amuse ourselves in the meantime.

Italian has inherited the consecutio temporum, a grammar rule from Latin that disciplines the relationship between the tenses in subordinate sentences.

Consecutio temporum has rules that govern the subjunctive tense in order to express contemporaneity, posteriority and anteriority in relation to the principal sentence. French and Spanish follow these same rules, which are often titled agreement of the tenses, or some such similar phrase.

- to express contemporaneity when the principal clause is in a simple tense (future, present, or simple past,) the subordinate clause uses the present subjunctive, to express contemporaneity in the present.

- Penso che Davide Galassi sia intelligente. I think David Galassi is smart.

- when the principal clause has a past imperfect or perfect, the subordinate clause uses the imperfect subjunctive, expressing contemporaneity in the past.

- Pensavo che Davide fosse intelligente. I thought David was smart.

- to express anteriority when the principal clause is in a simple tense (Future, or present or passato prossimo) the subordinate clause uses the past subjunctive.

- Penso che Davide sia stato intelligente. I think David has been smart.

- to express anteriority when the principal clause has a past imperfect or perfect, the subjunctive has to be pluperfect.

- Pensavo che Davide fosse stato intelligente. I thought David had been smart.

- to express posteriority the subordinate clause uses not subjunctive but indicative mood, because the subjunctive has no future tense.

- Penso che Davide sarà intelligente. I think David will be smart.

- to express posteriority with respect to a past event, the subordinate clause uses the past conditional, whereas in other European languages (such as French, English, and Spanish) the present conditional is used.

- Pensavo che Davide sarebbe stato intelligente. I thought that David would have been smart.

- Some third conjugation verbs such as capire insert -isc- between the stem and the endings in the present. Capisco, capisci, capisce It is impossible to tell from the infinitive form which verbs exhibit this phenomenon, which often originated in Latin verbs denoting the “inchoative” aspect of an action, that is, verbs describing the beginning of an action.

- There are some 500 verbs like this, the first ones in alphabetic order being abbellire, abolire, agire, alleggerire, ammattire and on through the alphabet.

- In some grammatical systems, “isco” verbs are considered a fourth conjugation, often labelled 3b.

- There are also certain verbs that end in -rre, namely trarre, porre, (con)durre and derived verbs with different prefixes (such as attrarre, comporre, dedurre, and so forth). They are derived from earlier trahere, ponere, ducere and are conjugated as such.

The Italian subjunctive mood is used, as in other languages, to indicate cases of desire, express doubt, make impersonal emotional statements, and to talk about impeding events.

|

Present |

Imperfect |

| 1st Conj. |

2nd Conj. |

3rd Conj. |

1st Conj. |

2nd Conj. |

3rd Conj. |

| io |

parli |

tema |

parta |

parlassi |

temessi |

partissi |

| tu |

parli |

tema |

parta |

parlassi |

temessi |

partissi |

| egli |

parli |

tema |

parta |

parlasse |

temesse |

partisse |

| noi |

parliamo |

temiamo |

partiamo |

parlassimo |

temessimo |

partissimo |

| voi |

parliate |

temiate |

partiate |

parlaste |

temeste |

partiste |

| essi |

parlino |

temano |

partano |

parlassero |

temessero |

partissero |

|

Past = present of avere / essere + past participle |

Past perfect = imperfect of avere / essere + past participle |

The subjunctive in many European languages is formed in the ‘opposite’ way from the indicative. So, if you have an -are verb like cantare, she sings is canta, but in the subjunctive, may she sing, or it is good that she sing, or may she sing forever, is cante. The -are verbs appear like -ere verbs in the subjunctive. So it was in Latin so it is in all of Latin’s daughters.

When we say Viva México, we are using a subjunctive. The indicative mood for to live in Spanish is vivir. México lives is México vive. But to make a wish Long Live Mexico, we use the subjunctive Viva México.

It’s the same in English. You just don’t realize it because it is your native language. We say Mexico lives alongside the United States, but when we want to make a wish for a long life for our sisters and brothers over the border, we say Long live Mexico. Lives is the normal indicative verb and live is the subjunctive which is expressing, as it often does, a wish, a desire, a hope, a conjecture.

Maybe we should just look at some sentences in Italian that use the subjuctive. Here’s one: Credevo che avessero ragione. I believed that they were right.

The subjunctive is used because the speaker believes, thinks that they were right. If the speaker said, I knew they were right, she would use the indicative.

There is always a hesitancy, a doubt, an unsureness about the subjunctive. I have been spiritually in the subjunctive all my life. I’ve never been sure of anything. I see both sides to any given question. That is why I wrote Combination of the Two.

Non era probabile che prendessimo una decisione. (It wasn’t likely we would make a decision.)

Non c’era nessuno che ci capisse. (There was no one who understood us.)

Il razzismo era il peggior problema che ci fosse. (Racism was the worst problem there was.)

Ciao piccolina, sempre carina.

The subjunctive is so called because there is a main clause, often in the indicative, and then another clause is subjoined to the main clause. In Italian, the subjunctive is called congiuntivo (conjunctive). Same thing. There is a main clause and then the next clause is conjoined to it.

I wish (main clause) that you WOULDN’T BE so hasty (subjoined clause with subjunctive verb mood).

Penso che sia un bel film = I think it is a beautiful film. We use the indicative in both clauses in English, but in Italian they use the subjunctive in the second clause because a personal opinion is being expressed.

È sicuramente un bel film = It is surely a beautiful film. Here there is a sureness, so the indicative is used. My bass player Peter Albin lives in the indicative. Everything with him is certain and there is very little doubt or hesitation. This kind of certainty is just what you want in a bass player. I am the opposite. Everything with me is in doubt. I live in the subjunctive mood.

Spero che lui/lei mi telefoni. = I hope he/she will phone me (personal wish)

Vorrei che tu fossi qui. = I wish you were here.

Affinché la nostra storia continui, dobbiamo parlare = In order for our relationship to continue, we need to talk (purpose)

Mmmm, chi ha fatto questa bella foto?

Voglio che tu venga qui = I want you to come here. (wish, command) Note that in English we use the infinitive instead of the subjunctive.

È bello che Paolo venga qui = It is wonderful that Paul come here (impersonal). We don’t use the subjunctive nearly as much in English as they do in Italian.

The “congiuntivo” is also required with particular expressions such as:

- Impersonal forms » è necessario che, bisogna che, è importante che… tu venga al cinema – it’s necessary that, it’s important that… you come to the movie

- Comparative clauses » è il film più interessante che abbia visto – it is the most interesting movie that I saw

- Sentences introduced by » affinché – perché (so that), tranne che (a part that), a meno che (unless), sebbene – malgrado – nonostante (altough), purché – a patto che(provided that), come se (as if)

- Sentences introduced by the adjectives or pronouns » qualsiasi – qualunque (any),chiunque (whoever), dovunque (anywhere)

- Sentences introduced by the adjectives or pronouns » niente che – nulla che(nothing that), nessuno che (nobody that), l’unico/a che – il solo/a che (the only one that)

The conditional mood refers to an action that is possible or likely, but is dependent upon a condition.

|

Present |

| 1st Conj. |

2nd Conj. |

3rd Conj. |

| io |

parlerei |

temerei |

partirei |

| tu |

parleresti |

temeresti |

partiresti |

| egli |

parlerebbe |

temerebbe |

partirebbe |

| noi |

parleremmo |

temeremmo |

partiremmo |

| voi |

parlereste |

temereste |

partireste |

| essi |

parlerebbero |

temerebbero |

partirebbero |

|

Past = present of avere / essere + past participle |

Io andrei in spiaggia, ma fa troppo freddo. I would go to the beach, but it is too cold.

Mangerei un sacco adesso, se non stessi di fare colpo su queste ragazze. I would eat a lot now if I weren’t trying to impress these girls.

Many Italian speakers often use the imperfect instead of the conditional and subjunctive. While incorrect, this is somewhat tolerated in spoken Italian (rarely in written Italian, even if it used to be a correct form in past times).

Se lo sapeveo, andavo al mare. If I had known it, I’d have gone to the beach. (If I was knowing it, I was going to the beach.)

Sempre in giro, eh!

The Imperative mood, or, the command form:

|

1st Conj. |

2nd Conj. |

3rd Conj. |

| (tu) |

parla! |

temi! |

parti! |

| (Lei) |

parli! |

tema! |

parta! |

| (noi) |

parliamo! |

temiamo! |

partiamo! |

| (voi) |

parlate! |

temete! |

partite! |

| (essi) |

parlino! |

temano! |

partano! |

The verb ‘to be’ is irregular in many languages (even English!) and Italian is no exception: essere

|

Indicative |

Subjunctive |

Conditional |

| Present |

Preterite |

Imperfect |

Future |

Present |

Imperfect |

| io |

sono |

fui |

ero |

sarò |

sia |

fossi |

sarei |

| tu |

sei |

fosti |

eri |

sarai |

sia |

fossi |

saresti |

| egli |

è |

fu |

era |

sarà |

sia |

fosse |

sarebbe |

| noi |

siamo |

fummo |

eravamo |

saremo |

siamo |

fossimo |

saremmo |

| voi |

siete |

foste |

eravate |

sarete |

siate |

foste |

sareste |

| essi |

sono |

furono |

erano |

saranno |

siano |

fossero |

sarebbero |

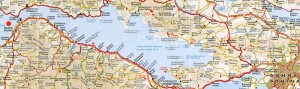

This is to give you an idea of how very different the dialects in Italy can be. To designate what the French would call ‘un jeune garçon,’ the usual word in Italian is ragazzo or bambino.

This is what the ‘jeune garçon’ is called in different places on the peninsula: in the Piedmont region, up north at the foot of the Alps, the ‘jeune garçon’ is called a cit.

In Lombardia, the ‘jeune garçon’ is a bagai.

In Venice, the word for a young boy is toso or putelo.

In Friulia, up north at the top of the Adriatic Sea, where a lovely town called Udine is, the local word for ‘young boy’ is frut.

‘Jeune garçon’ in the dialect of Emilia-Romagna is burdel.

In Tuscany, land of Dante, Petrarca, Bocaccio, and so many other immortals, that same ‘jeune garçon’ (young boy) is called a bimbo. There is a famous club in San Francisco, where we have all played a few times, called Bimbo’s.

It is crazy, insensitive and grammatically wrong to call a woman a bimbo, which is a very masculine word, both in form and meaning.

Quatraro is the word for a young boy in the Abruzzese dialect. This is only one word we are tracing here. See how different it is in each dialect? Almost all of the other words vary this much also, so you can see why people found each other incomprehensible once Italy was unified. Now, television, radio, cinema, Facebook, Twitter, newspapers… all of these contribute to the formation of a national language, and the old ways are disappearing.

In Naples a young boy is often called a guaglione. Do you know where the word Wop came from? The Spanish ruled Naples for a long time, a couple of centuries at least. They looked at the children in Naples and saw that they were very handsome, so they called them that. ’Handsome’ in Spanish is guapo. The word became so general a designation for the Italians that it was taken over at Ellis Island. Wop became a perjorative term for an Italian.

A ‘jeune garçon’ in Sicily is called a picciotto or a caruso. These are just a few of the regions of Italy.

Il confine tra passione e romanticismo può essere molto labile.

Noi stiamo bene. Dai speriamo di incontrarci.

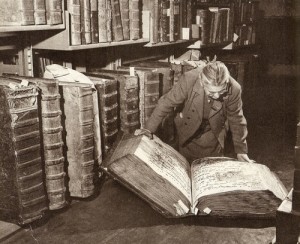

I used to have a book of Italian proverbs from every region, in the language of that region, and then ‘translated’ into Standard Italian. That book was a joy and very informative. Somehow I let it slip through my fingers, and I have been trying to find it ever since.

The top ten pizzas of Italy. I am a vegetarian, so I like the Margherita. Italians always laugh at Californians because we have things like tofu and pineapple on pizzas, but I notice that there at the number ten spot they have a pizza with fruit, cream and Nutella on it, so…

Ora più che mai…

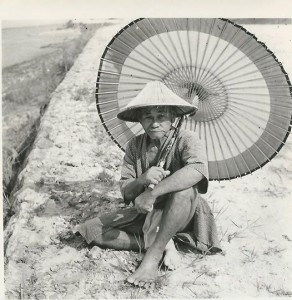

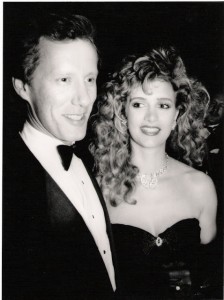

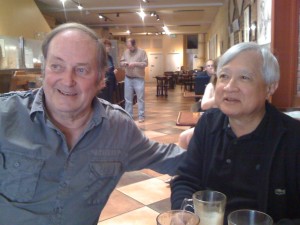

Sam Andrew Castelleto Cervo Italia foto: Laura Albergante Visconti La Laura è sconvolgente. Una vera bellezza.

______________________________________________________

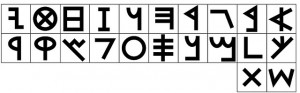

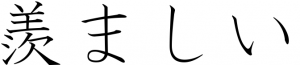

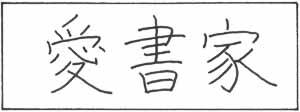

???????

???????

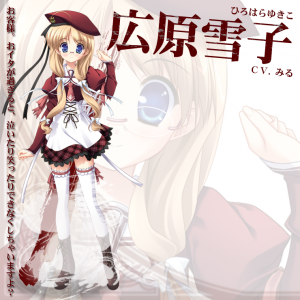

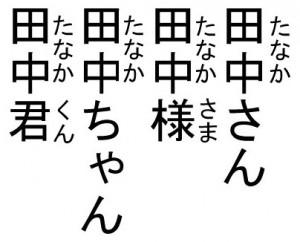

Yuki happiness, fortune

Yuki happiness, fortune Yuki will, intention, motive

Yuki will, intention, motive

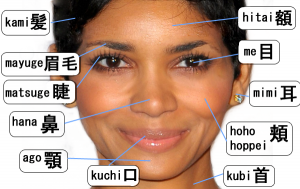

I have a teacher, a ??, on Okinawa. Her name is Nao, but she was probably born Naoko. Nao has several meanings. This kanji means big, large, great. Not the most flattering name for a woman.

I have a teacher, a ??, on Okinawa. Her name is Nao, but she was probably born Naoko. Nao has several meanings. This kanji means big, large, great. Not the most flattering name for a woman. This nao can mean furthermore/still/yet/more/still more/greater/further/less. Rather abstract for a woman’s name.

This nao can mean furthermore/still/yet/more/still more/greater/further/less. Rather abstract for a woman’s name. This nao means what it looks like: direct/in person/soon/at once/just/near by/honesty/frankness/simplicity/cheerfulness/correctness/being straight/night duty. I could see this word being used for a woman’s name.

This nao means what it looks like: direct/in person/soon/at once/just/near by/honesty/frankness/simplicity/cheerfulness/correctness/being straight/night duty. I could see this word being used for a woman’s name. Or this? I’m just guessing because I did not see Nao-san’s name written when I was on Okinawa.

Or this? I’m just guessing because I did not see Nao-san’s name written when I was on Okinawa.

Nao-san, left above, was my ?? sensei, teacher on Okinawa. These kanji read ‘Naoko,’ but she dropped the ko and became Nao.

Nao-san, left above, was my ?? sensei, teacher on Okinawa. These kanji read ‘Naoko,’ but she dropped the ko and became Nao.

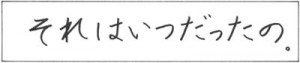

and in katakana is

and in katakana is  and in romaji is Naoko.

and in romaji is Naoko.

or

or  or

or  or

or  and several other ways as well. Sometimes a person will change the ‘spelling’ of her name for many different reasons at different stages in her life.

and several other ways as well. Sometimes a person will change the ‘spelling’ of her name for many different reasons at different stages in her life.