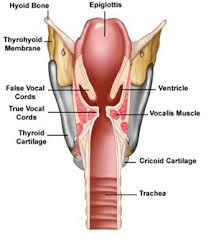

It must be said first and remembered always that song came first. All of the rest is based on the voice.

Most people who improvise anything do so intuitively. That’s the nature of improvising. It’s feeling your way to a solution. These flutes were used thousands of years ago, long before music was written. Long before there was any kind of music theory that we know. If you would like to improve your music theory and music then you may want to consider installing some home music systems.

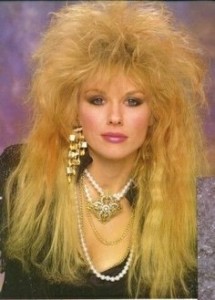

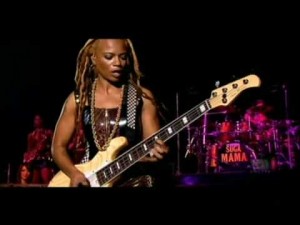

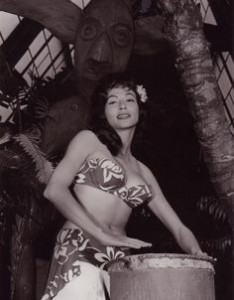

Photo: Max Clarke

Improvising is composing on the spot. Or, to put it another way, composing is improvising and then the writing down of that improvising.

All or almost all improvisers know how to put together a set of words or notes or images. They know this from inside. They always knew it. They didn’t learn it. It is instinctive for them. When someone sings a song, they can sing another line that matches that song and yet that is different. If you’re looking to sing with a little improvisation over an already produced beat or track you could look at sites like https://www.producerloops.com/ and start singing your heart out.

This improvised line of song can be close to the first sung line or it can be completely different, just as in a play where you can improvise a line that will fit into the plot and lead straight to the next scene, or where you can improvise a flight of fancy, wild and provocative, that will bring a new light to the action and only then will lead back into the drama.

In improvising you can be completely innovative or use material that you have reworked many times and remembered to bring it now to a new meaning.

In commedia dell’arte, a drama form from the Renaissance and before, the actors knew what a given scene was supposed to accomplish, but the actual dialogue was up to them. They improvised it.

There are some film directors who work this way. They will tell the actors what they are trying to accomplish and then will ask those actors to make up the lines that will move the story along. This can be an exhilarating and terrifying process.

A solo or a cadenza in a musical work is an improvised passage that will elaborate on the meaning of the song.

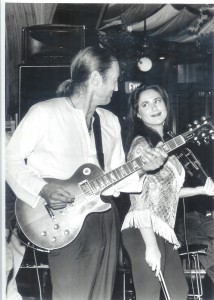

The solo can go off into a whole new territory, or it can stay close to the main idea of the piece and comment on that idea. The choice is up to the soloist. Franz Liszt used to murder his pianos onstage in front of hundreds of people. He was one of the great charismatic improvisors. Like Niccolò Paganini. Photo: Max Clarke

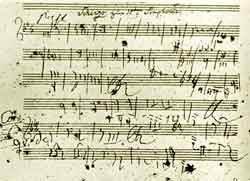

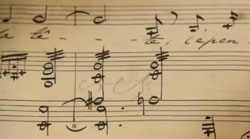

I once asked a classical violin player what scale she would use to play over an A7b9 chord and she gave me a blank look. I realized suddenly that she only played the notes on the paper and never gave any thought, perhaps, as to why those notes were there and not some other notes. It was not always this way in classical music. Mozart was an incredible improvisor and he played ex tempore for hours. If you love to listen to music, it is important that you have the right listening equipment so that you do not sacrifice on quality, as Graham Slee HiFi reports.

Beethoven played at parties and there are many stories of his improvising with passion and precision. When this man wrote “Freude,” he meant “Joy.” Foto: Maximiliano Clarke

Max Clarke found this license plate.

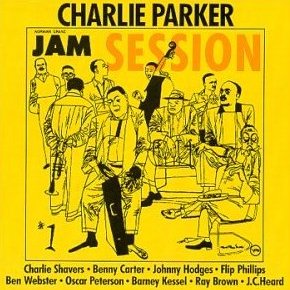

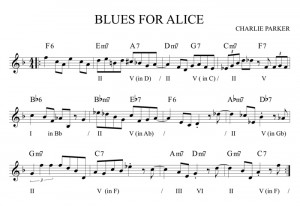

Some music, such as jazz, is mostly improvisation. A theme is stated at the beginning of the work and then each musician plays his idea of that theme, and, then, at the end, the theme is restated by everyone.

In early jazz in New Orleans, for example, the musical idea was stated at the beginning and then all the musicians improvised together on that idea until the end where the theme was again played by the entire ensemble. Everyone followed the chords, the harmony, of the piece but each person played his/her on take on that harmony.

Each musician is a composer in this style and often the solos were so beautiful and so complete that they were written down and they became different tunes in their own right.

A Max Clarke photograph

In the bop era (1940s more or less), Charlie Parker played songs like How High The Moon with such originality and verve that his solos became separate tunes in themselves.

One of his ideas on How High The Moon is called Ornithology.

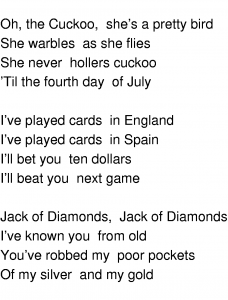

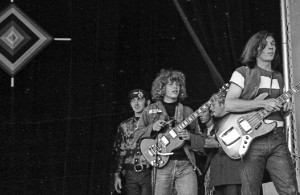

In Big Brother and the Holding Company, we played a song called Cuckoo for so long and with such wild abandon that it became a different song. We wrote some new words for it and called it Oh, Sweet Mary.

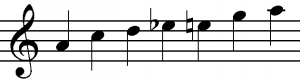

There are some tools that can be learned in music that will help when a great improvising idea occurs, so that the player will be ready to make the most of an inspired moment.

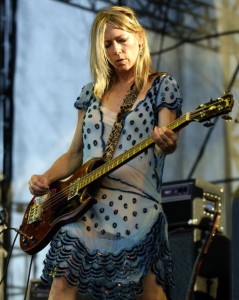

Photo: Max Clarke

It helps to have a personal collection of things to play over a given chord. Ideas that can be changed and put together in new ways. These ideas should be learned in all keys, of course, and in as many different time changes, as possible, so when the times comes, you can plug them in immediately and without conscious effort.

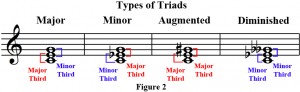

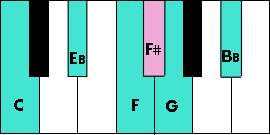

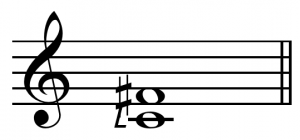

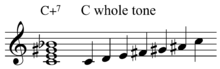

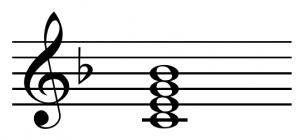

Most musicians learn the ‘spellings’ of the different kinds of chords: major, minor, augmented, diminished, dominant seventh, so they are not completely surprised when one of these sounds is called for.

The spelling of a chord is what the chord is made of, what makes a major chord different from a minor chord, or a minor from a diminished, and so on.

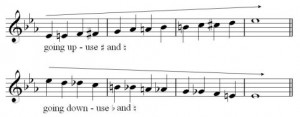

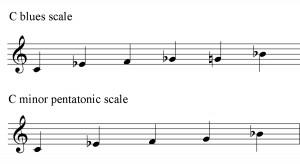

The chromatic scale is important. Improvising musicians learn how to play it from each finger. They learn this either consciously or unconsciously.

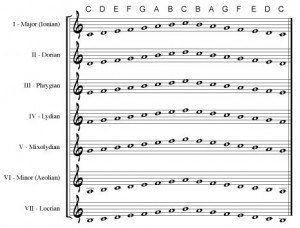

Learning the modes (‘moods’) is interesting and useful.

At first, the aeolian mode was the most interesting to us. James Gurley and I played in the phrygian mode quite often. Later the dorian mode became important. Some people have made a religion out of the lydian mode. All the modes are beautiful and each has its own character. Once again, to understand really what is going on here, each of these modes should be learned in all keys.

The mixolydian mode G A B C D E F G is used for the dominant seventh chord G7, so we played/play that one a lot, since rock and roll is mostly a dominant seventh kind of music.

And now I am going to ask my friends to tell me how they began to improvise and what moves them about their music. I’ll begin with the first improvisor that I knew, Jimmy Cuomo, who was fourteen years old when I met him and already incredibly accomplished.

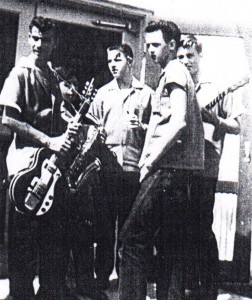

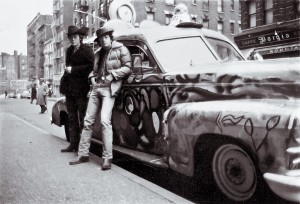

Jimmy is second from right here.

Jim Cuomo (second from left, barely visible) has this to say:

Rob Clores: I do remember the first time I improvised and it was also the first song I remember learning. Comin’ Home Baby.

I was 5 years old watching my father sit at the piano and play and sing the song. He showed me the basic chords. 5ths in the bass and the melody and after he left I basically tried to riff on the melody and make up my own variations.

So I guess it started out copying my dad but then I intuitively started to try to create pleasing patterns.

Rob Clores did the New York version of Love, Janis, with me and then we played a spectacular concert in Central Park.

Jan Koopman lives in the Netherlands. He writes: First I got when eight years old classic piano lessons, and after a few years my father bought an electronic organ for me, this gave me more fun.

Jan Koopman is the master of one of those instruments, the Hammond B3 organ, that you play with everything you’ve got, both arms, both legs, all your fingers, all of your brain, all of your heart and soul.

Kristina Kopriva Rehling: Jazz Saxophonist Richie Cole, heard me practicing classical Music on my Violin, came thru the door at my Parents Private School, his Daughter 4 was a student of mine, Annie . He said to me, “you’re never going be complete sticking w/ Classical,” I said why? He said…” 1. Kristina, you’ve got too much soul . 2. You’re bending notes all over the place in your Bach piece, and it’s a clear giveaway that you need to fly away into Jazz & Blues.”

He then invited me to play w/ him at The American Music Hall. He went easy on me the first time, Blues in C I think. We traded 4?s, and I could not wait to learn more:)

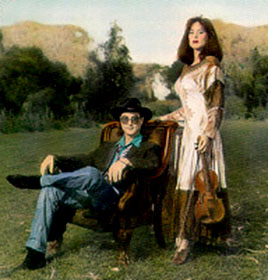

That’s Kristina Kopriva Rehling, beautiful woman, talented violinist, good friend. She sang a set with us at the Sebastiani Theatre in Sonoma last year.

Jesse Malley : I think that in a way I have always been an intuitive improviser. In my late teens, I remember jamming with some bands and being able to improvise melodies and lyrics, but I was very shy about it.

My confidence (or lack of it) stood in the way of my gut feeling, as well as straining everything through my brain before it came out, compromising my ability to be in the moment.

When I moved to LA in my early 20?s and started singing at open mic blues nights, all of these distractions seemed to disappear with every song. I started paying attention to the band, to the cues, less attention to the audience and my thoughts, and just started playing from my gut. The more I played out with strangers, the less I feared the unknown on stage. More than anything, playing live shows has been the best experience I’ve had in learning to play off the charts.

Learning to read body language, and paying attention to the other musicians on the stage. My breakthrough would have to be when I was about 23, when I stopped being terrified of improvising, and started being able to enjoy it. I think after you’ve had a few mistakes, blunders or train wrecks onstage, the worst case scenario doesn’t seem so bad anymore.

Jesse Malley performs in San Diego these days, and I am hoping she will come and join Big Brother for some shows in that area soon.

Arne Frager from the Record Plant checks in with this: I studied piano classical music as a young child of 5 years old and studied piano until the age of 18.

At the age of 12 I took up the upright string bass in junior high and played in the orchestra and began to play in pop bands and jazz groups. Since I read music and could sight read, I usually had a lead sheet or a fake book to guide me.

That’s Arne Frager, bass player, talented musician, producer, genius in residence.

Anthea Sidiropoulos: I remember wanting to learn to scat and listened to Ella Fitzgerald’s A tisket A tasket, How high the moon – mimicked her scatting – then moved on to other standards and found I could not only emulate the scats but build my own take on them. I remember gaining an awareness during my early childhood when i was having private piano and music theory tuition. This gave me an understanding about scales, keys and the mechanics of music.

This gave me confidence and allowed my improvising ability to ‘fly’ and ‘dance’ around musical arrangements. I remember my teacher including ‘ear’ exercises as my aural abilities excelled during these formative years. I would say this would have contributed to how I learned to improvise. I could ‘hear’ where my vocal notes ‘felt’ right and where they felt they did not fit in the piece.I never ‘learned’ to improvise per se – it seemed to happen naturally, especially as my courage and confidence increased. A ‘freeing’ experience of the soul if you like. I can relate this to meditation at times, especially when chanting.

I grew up in a family where singing was a given, (privately though.. anything further was a no, no) and my parents harmonised naturally as the Greek folk songs allowed for this as the norm. I picked up a natural ability to harmonise on virtually any melody. I started improvising along with harmonising to the tune. formative years of piano and music theory and after a 15year gap of music where I regained the ability to improvise again.

Anthea Sidiropoulos lives in Melbourne, Australia, and I am hoping to do some shows with her there.

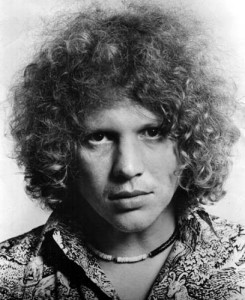

Barry Melton: I was born into a left-wing activist family and my earliest years were spent in a small enclave of folks in Brooklyn, New York.

Woody Guthrie was a neighbor (I went to Marge Guthrie’s dance school for a while), my dad was friends with Paul Robeson and I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know Ramblin’ Jack Elliott.

I’m told I was at the Peekskill riots as a toddler and my mother sang and played folk music on the piano – songs of the Spanish Civil War, the Civil Rights struggle, blues and just plain folk music from all over the world.

My parents were determined I would be a musician and play for the struggle, so they made sure I started young, really young.

It was my idea to become a lawyer when I grew up, but it’s not in the least ironic that I started my adult life just as my parents had planned – on stage with a guitar in my hands.

My first guitar instructor was not a guitarist. He as a retired violinist from the New York Philharmonic. I was trained classically on guitar from the age of five to approximately the age of eight. I literally learned to read and write music around the same time as I learned to read and write English. Mr. D’Aleo was an older adult, perhaps in his 70’s. He was extraordinarily disciplined and drilled me incessantly; he also taught me music theory, and a significant component of my instruction involved reading and writing music (on staff paper).

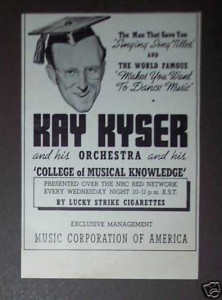

Things couldn’t have taken a sharper turn when my family moved from New York to Los Angeles in 1955. Milton Norman, my first and only guitar instructor in Los Angeles, was a ‘50’s avant garde jazz guitarist. He played with the Kay Kyser big band and a host of small jazz combos.

But his approach to the instrument was mostly “chordal,” i.e., for him guitar was a rhythm instrument that used complex chords to help lay the foundation for horn-playing soloists, pianists and singers.

From 1959 on, at age 12, I was thoroughly captivated by the folk music revival. And wow, was I ready: Kids all over the place seemed to be adopting the music I grew up with. My parents’ friends were becoming icons. I listened assiduously to the folk show that Les Claypool hosted on FM radio.

I played my guitar with such ferocity that, during my transition into puberty, I nearly got my family evicted from our modest apartment in the San Fernando Valley.

By the age of 14, I was getting friends just a few years older – Bill Bernds, Bruce Engelhardt, Steve Mann – to drive me around L.A. and join in numerous blues and folk jams across the Valley and over the hills into Hollywood.

And Steve Mann, a near-neighbor who shared my passion for country blues, was becoming a star, ultimately playing on the first Sonny & Cher recordings and backing Gale Garnett on “We’ll Sing In The Sunshine.”

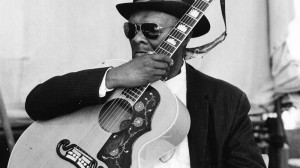

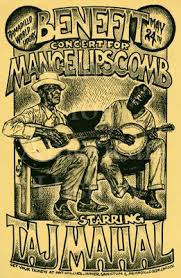

It was there, in the foyer of the Ash Grove on Melrose Avenue in Hollywood (McCabe’s Guitar Shop was a little annex in the front part of the club, as was the foyer) that I and a host of young and aspiring musicians (Taj Mahal, Ry Cooder) got to “jam” with virtually every musician who came through town.

Brownie and Sonny, Doc Watson, Mance Lipscomb, Gary Davis and a long list of names that, for me, touch the very essence of where my music comes from.

And the circle, that was sometimes small and sometimes too big for the room, had a participatory component that left room for anyone who had something to contribute to play a little louder while the rest of the circle accommodated whoever was soloing.

By the time I got my own car on my 16th birthday, I drove for the single purpose of picking up blues and folk musicians on tour and taking them around town, or as part of my never ending quest to jam with other musicians in some blurred scrabble of black and white, blues and country, music.

I drove my high school friend, Bruce Barthol, out to the prophet in Woodland Hills to participate in the “Hoots” run by folksinger Michael Wilhelm; or, on one ill-fated voyage to a party at the Chambers Brothers Jug Band’s house in Silver Lake, my friend Steve Mann riding shotgun managed to get us busted and he went to jail, while I got detained as a juvenile and my parents were called.

As a devoted “folkie,” I had a belief that real music had to be learned from the oral tradition and it was inauthentic to learn from recordings. So I sought out musicians to “lead,” as was the blues tradition as I understood it. I drove Mance Lipscomb around when he first came to Los Angeles, and it was honor and privilege to “lead” Bukka White and Rev. Gary Davis, too.

I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to say I played guitar 40 hours a week between the ages of 12 and 18; and I’m often surprised and delighted to realize I actually squeezed something of a crude education into the mix.

I’ve known Barry Melton a long time now, almost fifty years. He gave me some good advice about how to construct my solo on Piece of My Heart. If I were ever in trouble legally, he is the man I would see, because he is a lawyer and I’m not.

Jack Perry: I was forced into improvising when first given a guitar with no lessons attached, no chord chart, not even decent radio reception. So I developed by way of the “hunt and peck” system. If something sounded good, I tried to memorize it to mix it in with other such riffs.

I think a friend at school taught me the opening notes to Windy so I began integrating a more traditional scale approach to the hunting and pecking.

Some months later a friend taught me the first few lines of Santana’s Black Magic Woman (over the phone!) , so I added more of a blues scaling and technique.

I performed Black Magic Woman in an early combo of friends to a church crowd. I had only ever memorized those first few lines, the rest of the performance was an improvised extension of them.

Jack Perry now plays differently tuned guitars in a very original and beautiful context. Just the pure sound of these guitars is emotional and beguiling.

My friend Jason Castle writes: My first experience with music for many years was singing. So, I learned by ear, including how to harmonize, thanks to my mother’s experience singing harmonies with her father and sisters (who all sang in the choir at church). When I was in grade school, I sang in a trio with two girls, and we just made up the harmonies, improvised them, I guess you could say.

Go with the flow.

Kurt Huget writes: My first explorations in improvisation began in my early teens, on both guitar and piano, playing along with records and the radio. I found that I needed a lot of time and patience to delve into it, so I gravitated towards the music of blues bands and the great San Francisco rock bands, because their songs often stretched out longer than the typical 2-3 minute pop tunes of the time.

It gave me the freedom to try out any musical ideas that came to mind, change course when they weren’t quite sounding right, and work out riffs and themes, step by step.

Learning the blues pentatonic scale was a big breakthrough, because it gave me the musical vocabulary to take a solo anywhere I wanted to.

Such a simple scale, but with endless possibilities.

I must add that, at times, smoking pot helped in the improvisation process.

I think that smoking pot freed me up to play more intuitively, that is, to “feel” the music, rather than “think” it.

My guitar buddy Greg Douglass weighs in with this: I started off taking lessons from a fellow who recognized that, beneath the timid & clumsy musical veneer I presented to him every week, there was at least a proton's worth of talent. He attempted to remake me in his image as a jazzer. Being 14 and having just seen The Beatles on Ed Sullivan, I not only rejected being the next Kenny Burrell but quit lessons entirely to devote private study to pop music structures and how to pick up girls.

I slavishly copied solos and changes and, in doing so, learned about how to put together a song, even prior to learning the Circle of Fifths.

However, I lived in the Bay Area. The pendulum was swinging heavily towards more freedom; extended solos, Eastern modes, feedback...freedom! Suddenly, I had all the room in the world to move musically and no knowledge to back it up.

I was still stuck in the minor pentatonic ghetto that so many of my guitar students still find themselves mired in to this day. My band, a Top 40 cover band, discovered pot and began experimenting musically.

I spent hours on my couch at U.C. Berkeley, creating the basic outlines to long solos and desperately trying to solve the puzzle of the fretboard. I still felt like a fraud and a one-trick pony...hell, I was learning to play guitar in front of large crowds, opening for people like Ten Years After and Jeff Beck.

Humility came very easily to me. I knew next to nothing and was jamming one-on-one with guys like Terry Haggerty and Peter Green. The bar was set very, very high.

Two fortuitous things then happened. I quit Berkeley and went to DVC, a junior college in Concord CA. I took 3 music courses, Theory 101 and Harmony 1 & 2. I learned about the rules, I did sight-singing (I still have nightmares about sight-singing to this day!), I wrote pieces for string quartets (and ended up dating the smoking hot cello player)....I learned about music in a holistic, non-guitar-oriented context.

But...I would still look at the neck and go blank. "That's an A note!", I would proudly explain. There was still no grand scheme on the guitar neck. I could not see things in a logical, musical pattern. I got by for ages with a kind of false bravado and a macho ethic of "When in doubt, play really, really fast!".

One day, I picked up a book of scales. The scales were shown separately, but given a context: there were chord shapes the scales were hung on. After learning the separate scales, I learned how to play the scale positions as they flowed into one another. One day, I looked at the neck and saw not a chaotic blur of separate notes, but a recurring pattern of chord shapes that was never-ending and gave birth to a new world of melodic possibilities.

I had "discovered" the CAGED method about 5 years into my six-stringed journey, and everything was different from that day forward. I had the knowledge from my years spent poring over difficult problems in harmony, but now there was a practical basis for everything. I understood modes, I understood what went where and why...I understood the rules well enough to break them with confidence.

My greatest gift as a teacher is being able to explain these musical parameters to others on a daily basis. While the names "Douglass" and "Coltrane" won't be put next to one another anytime...except perhaps alphabetically..I know enough to enter improvisational situations with a sense of confidence, potential fun, and adventure. I often use advice I've given to a student when I'm onstage to help me break out of my own self-created ruts.

Nothing makes me happier than confronting a wall of apathetic ears in a smooth jazz type setting (restaurants, cocktail parties...funerals..) with a swift barrage of whole tone runs or a series of tritones (nothing like The Devil's Interval to put a dent in some aging debutante's carefully coiffed composure!).

That's Greg Douglass, the original Diabolus in Musica.

Wesley Freeman, left, with brothers Ming and Tracy, writes to me : I first thought about improvisation when I went to the Kadena Officers Club on Okinawa one night.

I think I was about 16 at the time, and I went there to watch my guitar teacher Tiny Umali play with his jazz trio. He not only played these wonderful complex chords, but he played all these notes around them, and from that moment on, I was fascinated by the idea of being to play beyond just the chord and the original melodies.

I watched a lot of people play after that, and paid close attention to how they took the melodies and would build on them, creating landscapes in the air.

Jude Gold: Yes, I remember the very moment I first started improvising on guitar. Kind of like the day I first rode a bike. I remember it.

Next, I recall trying to play songs by ear, that were above my reading level on piano, when I was about six. My improvisation would include “learning” songs like “the entertainer”, where I would fill in the missing gaps of music I didn’t know with improvisational parts until I could modulate back to the next part I could remember.