The Japanese Language

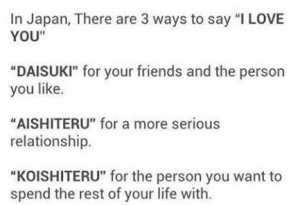

???????????????????? Koko ni eigo o hanaseru hito wa imasu ka. Does anyone here speak English?

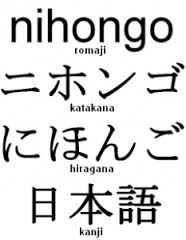

Nihongo Japan language

Ni hon go

All license plate photographs are courtesy of Max Clarke.

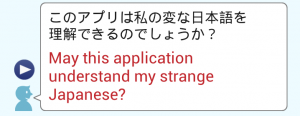

| For native English speakers, the Japanese language is one of the hardest languages to learn which is why Japanese translations services remain in demand at the moment. It is difficult for us to learn to speak well, because it is unlike English in almost every way. Yes, the writing is very difficult, but the thought process itself is almost the complete reverse from English. These facts make Japanese a fascinating and interesting language to study. |

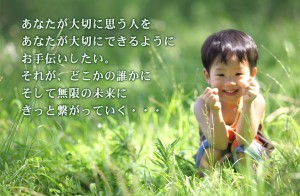

Japanese is quite similar to, of all languages, Latin. Both idioms are heavily inflected, so there is often no need for pronouns. Pretend you are sending a telegram where every word costs a lot. So you are going to try to say something meaningful with absolutely as few words as possible. That’s Japanese. You don’t say ‘I bought,’ you say ‘bought.’ ‘I bought a book’ becomes ‘bought book.’ You don’t say ‘I love you.’ You say ‘loving.’ This isn’t slangy or colloquial. It is built into the language which is telegraphic in the extreme.

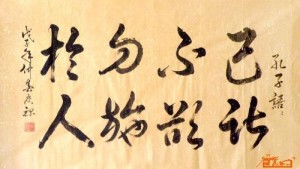

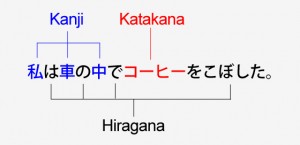

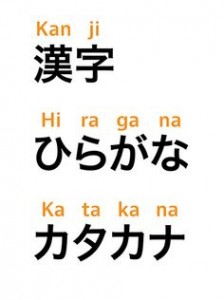

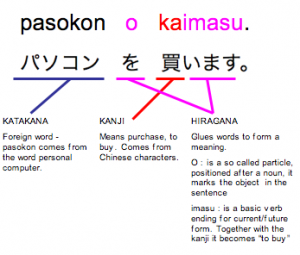

There can be, and often are, four different writing systems in one Japanese sentence, anyone of which would be sufficient to write the entire language: kanji, hiragana, katakana and Romaji (Rome letters, which is what the Japanese call our alphabet).

Or, as one of the early Jesuits in Japan, probably Matteo Ricci, put it, one hesitates for an epithet strong enough to describe a language where a separate writing system is required to explain the existing writing system.

Three different writing systems on one subway sign. Any one of these systems would be capable of writing Tokyo Metro Ikebukuro Station.

Japanese has cases like Latin or German or Russian. There are small one syllable words to mark what case it is. This word wa can mark the nominative case.

- ? wa for the topic which can be different from the subject of the sentence.

- ?????????? Watashi wa sushi ga ii desu. (literally) “As for me, sushi is good.” or I like sushi.

Yesterday I book bought. ![]() Yesterday book bought. The word order is like Latin. Subject, Object, Verb.

Yesterday book bought. The word order is like Latin. Subject, Object, Verb.

???? yamato kotoba wago ?? The words the Japanese use for their original, native language before the adoption of so many Chinese words which came along with the Chinese writing system.

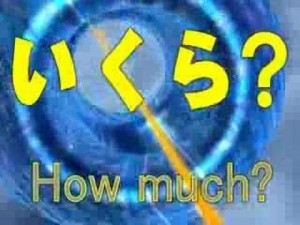

I ku ra (how much?): Until you get a feel for how Japanese is stressed, it is probably a good idea to put equal stress on every syllable. Count 1,2,3 and listen to how you say each number very evenly. Then try to accent the Japanese the same way. 1 2 3 i ku ra. Give the last syllable as much stress as you do the second syllable. 1 2 3. I ku ra.

I ku ra. I put ra in italics, because for English speakers, there is a strong tendency to swallow or minimize that last syllable, I ku (ra), but in Japanese it is as strongly pronounced as the other two syllables. 1 2 3. I ku ra.

Remember to ‘roll the r’ so to an Anglophone the word will sound like i ku da.

English speakers like to accent the penultimate syllable, so for the airport name in Tokyo, Narita, what English speakers say is something like ‘Na REE da,’ (same stress pattern as I need a…) which no Japanese is going to understand. Say Narita like 1 2 3 Na dee ta 1 2 3 and at least you will be understood. Be sure and pronounce the T as in Tom, and roll the r. Because your giving equal stress to each syllable, it will sound to you, an English speaker, as if the last syllable is the one stressed but it is merely being given equal stress which you are not used to hearing.

If you say Na dee TAH, you will be much closer to the actual Japanese pronunciation of this airport name.

Here is an example of two phrases that we use that have three equal parts with almost equal stress. They are: coup d’état and ‘stay on top.’

If you say Narita with even stress on each syllable, as in coup d’état, it will be much more comprehensible than the Na REE da that rhymes with ‘Juanita.’

1 2 3 Na ri ta. Stay on top.

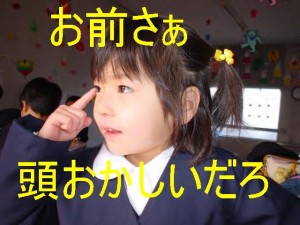

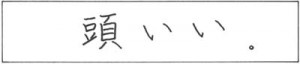

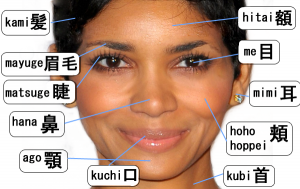

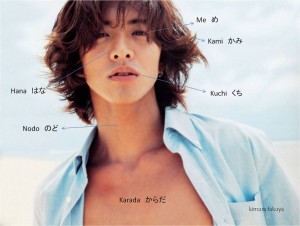

Head good. Atama ii. She’s smart. She has a good head. See how telegraphic the language is? In English, we say ‘Smart,’ and that gets the idea across, but ‘smart’ is colloquial, laconic. Not in Japanese. In Japanese ‘head good’ is a perfectly normal way to say ‘she’s smart.’

![]() You are smart. (As for you, head good.)

You are smart. (As for you, head good.)

Japanese has a stress system that sounds to us like a metronome. Very even and, to us, unaccented. Our language is so stressed, so accented that imPORtant SYLlables tend to LEAP OUT at you. UnderSTAND? Japanese is much more even.

When you hear a Japanese speaker speaking quickly, the speech can sound like those syllables that Indian tabla players say. Japanese can sound like a drum solo.

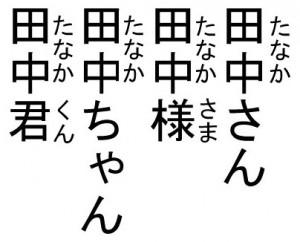

?????????? Kochira wa Tanaka-san desu This is Ms./Mrs./Mr. Tanaka.

??????????????????????????

Tanaka-san is rich, handsome, and charming, isn’t he?

Different ways to address someone, male or female, who is named Tanaka. The first vertical line of characters on the left is Tanaka-kun. This is the way young people address each other.

The second vertical line above reads Tanaka-chan, and this is an imitation of the way babies pronounce ‘san,’ so it is used to speak to infants and small children or someone very familiar to the speaker.

The third line is Tanaka-sama. Sama is an honorific title, almost like saying ‘reverend,’ or ‘honored.’

The first vertical line on the right above is Tanaka-san, the usual way of addressing someone named Tanaka.

Dative case: ???????????? Tanaka-san ni agete kudasai Please give it to Mr. Tanaka.

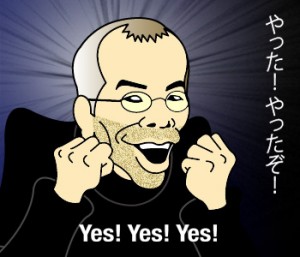

Yatta! ???! Did it! He doesn’t see the need to say ‘I.’

?????? Kare ga yatta. He did it.

It’s cool. Kakkoii.

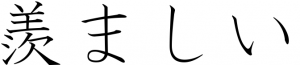

Urayamashii! ????! Jealous! I, you, she, he, it, we, they The pronoun is unspecified and depends on the context. Japanese is a very ‘telegraphic’ language. If someone says in English, “What are you doing?” you can say “Thinking” because the context makes it clear who is thinking.

It’s the same in Japanese, only more so.

Oshiete moratta She explained it to me.

Oshiete ageta (??????) [I/we] explained [it] to [him/her/them]

??????????????Odoroita kare wa michi o hashitte itta. The amazed he ran down the street.

This isn’t said this way in English but it is in Japanese. I suppose it’s more like Amazed, he ran down the street.

Ablative case: ???????? Nihon ni ikitai “I want to go to Japan.”

???????????? p?t? e ikanai ka? Won’t you go to the party?

Genitive case: ?????? watashi no kamera my camera

????????????? Suk?-ni iku no ga suki desu (I) like going skiing.

- ? o for the accusative case. Not necessarily an object. ???????? Nani o tabemasu ka? What will (you) eat?

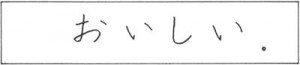

Oishii. Delicious. You hear and say this word very often in Japan.

Oishii. Delicious. You hear and say this word very often in Japan.

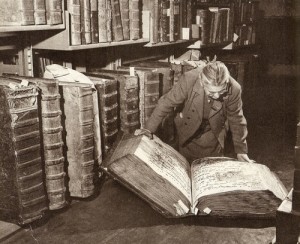

hon (?) book, books There is no plural. It’s like ‘sheep’ or ‘deer.’ Every noun in Japanese can be singular or plural.

? hito person or people

ii desu (????) It is OK. ii desu-ka ??????Is it OK?

????? O namae wa (What’s your) name?.

Pan o taberu ??????? I will eat bread or I eat bread

Pan o tabenai ???????? I will not eat bread or I do not eat bread Pan o tabenakatta ?????????? I did not eat bread.

???? hen na hito a strange person

Photo: Max Clarke

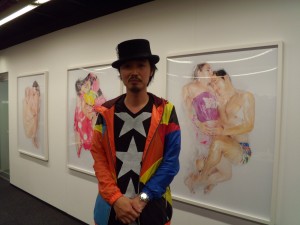

Gai jin: We are often called this when we are in Japan. ![]() henna gaijin weird foreigners

henna gaijin weird foreigners

The first rule of saying “you” in Japanese is that you don’t say “you” in Japanese. That’s only a slight exaggeration.

It is worth noting that the word you isn’t in any of these three sentences. In day to day speech there are very few pronouns in Japanese.

?????? Kimi no Na wa Kibou Your name is hope. kimi “you” (? “lord”) Kimi is a word for you used by boyfriends for their girlfriends.

?? Anata “you” (??? “that side, yonder”) Married women use this ‘you’ when speaking to their husbands.

It then comes to mean something like the American affectionate term ‘honey.’ If written ?? (anata), the person addressed is female.

?? (omae) – your pet, someone very close to you or someone you hate. It literally means in front or facing.

? onore Someone you really hate

?? kisama This is a you that you really don’t like.

? nanji thou

?? (sonata) archaic and similar to thou

??? temee Someone you really hate

You might be yakuza you hate them so much.

?? otaku someone emotionally distant and unknown to you

Pronouns are not much used in Japanese. In fact, they may be less used than anywhere else in the world. Here are, however, some pronouns for I/me and what they say about the speaker. The most common word for I is ? watashi. Japanese often point to their nose when we would point to our heart to say “Me?”

Once again, try to keep the syllable stress equal until you get a feel for the accent. The stress really is there, but it is much more subtle than in English, so try to say ? watashi the way you would say 1 2 3 with equal stress on each syllable. wa ta shi 1 2 3.

Listen carefully to how a native speaker says the word.

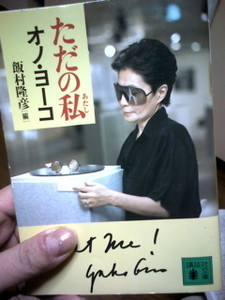

? atashi Almost the same word as watashi and it is written the same but this word is used by girls and guys-who-want-to-be-girls only. Yoko is saying atashi here. How do I know? Because those little tiny characters to the right of ? say atashi. Those small ‘letters’ are called furigana and they are what I was talking about earlier when I quoted the Jesuit who said something like ‘one hesitates for an epithet strong enough to describe a written language that needs another written language to explain it.’ Furigana are often used, as here, to give the ‘alphabetic’ (actually ‘syllabic’) rendering of a kanji. They are often used in childrens’ books and in texts for non Japanese speakers. It seems very out of character to me that Yoko would call herself atashi. She seems a much stronger character than that, although atashi perfectly renders the English Just me! The middle line says Ono Yoko in katakana. So here you see on one signboard four systems of writing, kanji, hiragana, katakana and romaji.

? watakushi, first person pronoun used by rich old men, butlers and princesses.

? boku has the literal meaning servant. Used by female or male prepubescent children or young boys.

? ore This is the rough, tough I. Truck drivers, lumberjacks and other manly men use it.

? ora How farmers and other rural people say ‘I.’

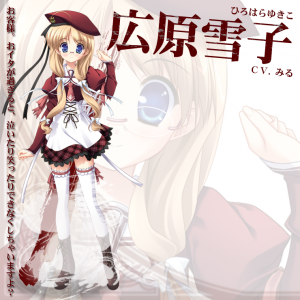

I have a friend named Yukiko but I am not sure what kanji she uses to write her name. There are several choices.

Yuki happiness, fortune

Yuki happiness, fortune

Yuki will, intention, motive

Yuki will, intention, motive

American speakers say her name like Yu KEE ko to rhyme with ‘you freako,’ but Japanese say her name like 1 2 3. Yu Ki Ko to rhyme with ‘don’t you know?’ The Ko is as important as the Ki. More important actually, since Ko has a separate meaning. Yukiko’s husband Peter calls her Yuki. It’s a more grown up name.

Yukiko means Yuki girl, or even Yuki child, so there has been a feminist movement in Japan to drop the Ko after women’s names. The woman’s name becomes Yuki, or Yo, or Nori, instead of Yukiko, Yoko or Noriko.

I have a teacher, a ??, on Okinawa. Her name is Nao, but she was probably born Naoko. Nao has several meanings. This kanji means big, large, great. Not the most flattering name for a woman.

I have a teacher, a ??, on Okinawa. Her name is Nao, but she was probably born Naoko. Nao has several meanings. This kanji means big, large, great. Not the most flattering name for a woman.

This nao can mean furthermore/still/yet/more/still more/greater/further/less. Rather abstract for a woman’s name.

This nao can mean furthermore/still/yet/more/still more/greater/further/less. Rather abstract for a woman’s name.

This nao means what it looks like: direct/in person/soon/at once/just/near by/honesty/frankness/simplicity/cheerfulness/correctness/being straight/night duty. I could see this word being used for a woman’s name.

This nao means what it looks like: direct/in person/soon/at once/just/near by/honesty/frankness/simplicity/cheerfulness/correctness/being straight/night duty. I could see this word being used for a woman’s name.

Or this? I’m just guessing because I did not see Nao-san’s name written when I was on Okinawa.

Or this? I’m just guessing because I did not see Nao-san’s name written when I was on Okinawa.

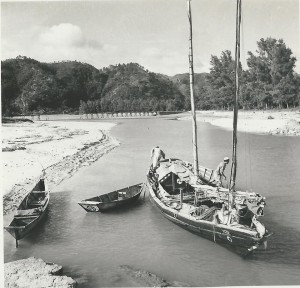

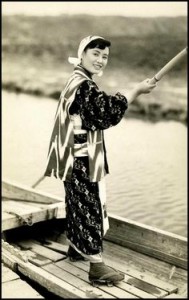

Nao-san, left above, was my ?? sensei, teacher on Okinawa. These kanji read ‘Naoko,’ but she dropped the ko and became Nao.

Nao-san, left above, was my ?? sensei, teacher on Okinawa. These kanji read ‘Naoko,’ but she dropped the ko and became Nao.

Photo: Wesley Freeman

in hiragana is

in hiragana is  and in katakana is

and in katakana is  and in romaji is Naoko.

and in romaji is Naoko.

Nao’s name  may be written several different ways in kanji alone. She can be

may be written several different ways in kanji alone. She can be  or

or  or

or  or

or  and several other ways as well. Sometimes a person will change the ‘spelling’ of her name for many different reasons at different stages in her life.

and several other ways as well. Sometimes a person will change the ‘spelling’ of her name for many different reasons at different stages in her life.

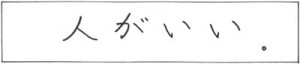

Hito ga ii. Good person. Good natured person.

?? atsui “to be hot”) which can become past (???? atsukatta “it was hot”), or negative (???? atsuku nai “it is not hot”). Note that nai is also an i adjective, which can become past (?????? atsuku nakatta “it was not hot” ?????? Gohan ga atsui. “The rice is hot.” ???? atsuku naru “become hot”.

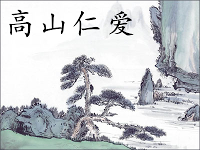

Takayama Jinai Japanese name written with four characters. Takayama means ‘high mountain.’

??? ano yama that mountain

???????????????

Omoshiroii. Interesting, funny.

She doesn’t think so.

The phrase under the images means Ten common phrases that stump Japanese students of English

This gentleman will pay for everything. ?????????? (konohito ga zembu haraimasu)

???? ?????????? Jissai ni atta koto da. It actually happened.

In Japan there are soft drinks named sweat and piss.

Donna shigoto o shite iru no.

What kind of work do you do?

?????????????????? Kare wa kawarimono da to hyouban daga jissai sou da. He is said to be eccentric and he really is.

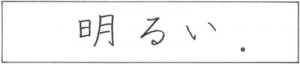

Cheerful. Akarui.

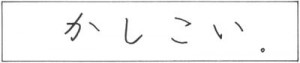

Clever. Kashikoi.

|

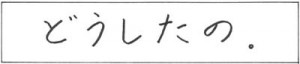

What’s the matter? (Doo shita no.)

I spilled coffee in my car.

????????? Dai joobu desu. That’s all right.

You hear the question ???????? Dai joobu desuka? a lot in Japan. Everyone is trying to reassure each other. Is it OK? Is it allowed?

???????????? attractive

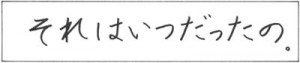

When was that?

Keizo

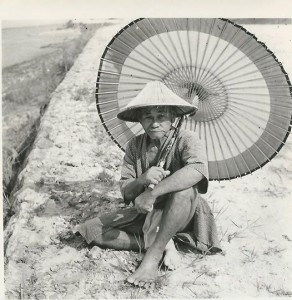

Sam Andrew Michel Bastian Kyoto 1995 Photo: Keizo Yamazawa

____________________________________________________________

???????

???????