Vaudeville

SANDERSON: My friend has been elected mayor.

BOWMAN: Honestly?

SANDERSON: What does that matter?

Acting drama was seriously curtailed with the onset of the Revolutionary War when the Continental Congress convened and passed a recommendation that the colonists “discountenance and discourage all horse racing and all kinds of gaming, cock fighting, exhibitions of shows, plays and other expensive diversions and entertainments.” The staging of plays all but ceased in the colonies.

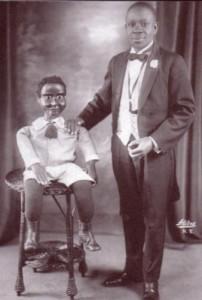

DUMMY: My father killed a hundred men in the war.

VENTRILOQUIST: What was he? A Gunner?

DUMMY: Nope, a cook.

With the coming of peace, the feeling against plays began to lessen, but it wasn’t until 1787 that the American theatre began to flourish. Philadelphia and New York City became the twin hubs of the theatre, vying for supremacy up through the period of the Civil War when other forms of entertainment began to emerge on the American dramatic landscape.

YOUNG MAN: I want to ask for the hand of your daughter in marriage.

OLD MAN: You’re an idiot!

YOUNG MAN: I know it. But I didn’t suppose you’d object to another one in the family.

The Cherry Sisters were considered the worst vaudeville act of all time. Ranging in number from five to two, their songs and recitations were so awful that audiences threw vegetables to show their disgust.

Managers saw the possibilities and encouraged audiences to hurl produce. The ladies drew huge cackling crowds, performed behind a net curtain to avoid injury, and they unsuccessfully sued complaining critics.

All evidence suggests that the sisters believed their act was really good. Commanding a hefty $1,000 a week, they toured for decades.

I just got back from a pleasure trip. I took my mother-in-law to the train station.

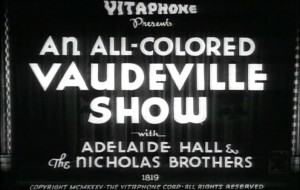

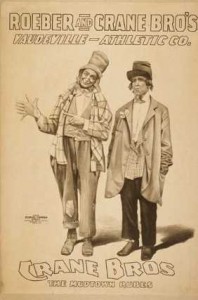

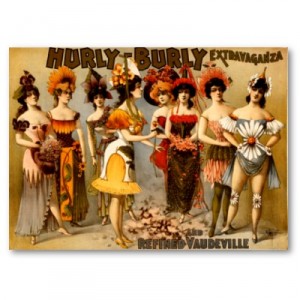

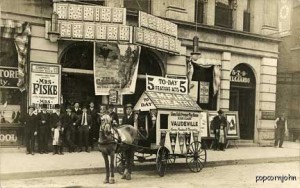

Vaudeville was variety. All the variety shows on television and onstage are descended from vaudeville which was popular in the United States and Canada from the early 1880s until the early 1930s.

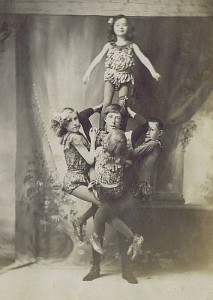

Each vaudeville show was made up of a series of separate, unrelated acts.

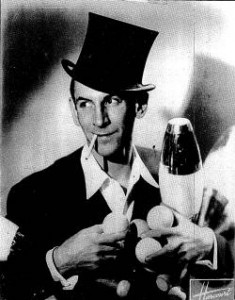

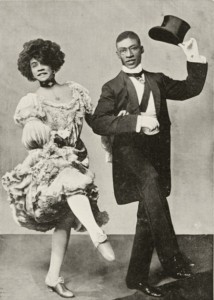

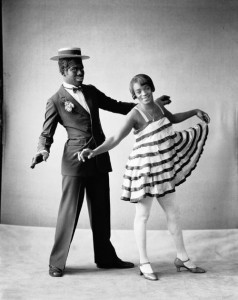

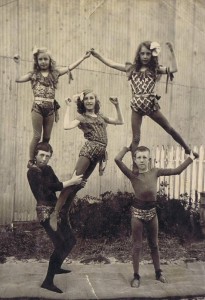

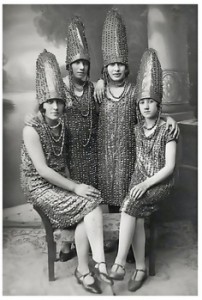

Vaudeville included such acts as popular and classical musicians, singers, dancers, comedians, trained animals, magicians, female and male impersonators, acrobats, illustrated songs, jugglers, one-act plays or scenes from plays, athletes, lecturing celebrities, minstrels and films.

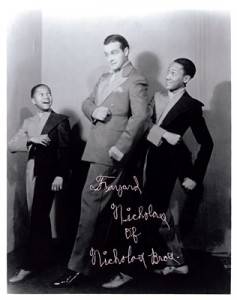

A vaudeville performer is often referred to as a vaudevillian.

Yiddish vaudeville joke: In Jewish tradition, the fetus is not considered viable until it graduates from medical school.

Vaudeville evolved out of the concert saloon, minstrel shows, freaks and geeks, dime museums and literary burlesque.

Vaudeville was “the heart of American show business,” for several decades.

The newest Jewish-American-Princess horror movie? It’s called, “Debbie Does Dishes.”

Many show business terms originated in vaudeville. When a performer’s name appeared on the top of the billboard listing each week’s acts, they were at the “top of the bill.”

Headliners got the best dressing rooms and the highest salaries, up to $4000 a week in the big time.

Imagine being ‘on’ for two to five shows a day! That’s difficult, I can tell you.

The performers didn’t necessarily have to have a lot of talent, but they made up for that with personality and extraordinary stamina.

Since many of these longtime audience favorites predated the age of talking film, their names are now forgotten, but a few are still with us.

They tried to kill us, we won, let’s eat.

Keith and Albee were self elected censors of vaudeville and the standards they imposed on all vaudeville acts were hard on comedians.

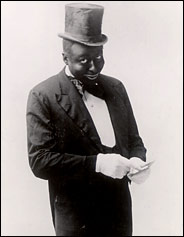

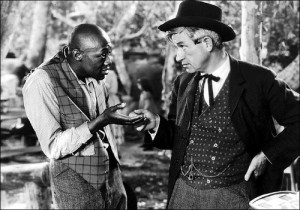

Working clean was difficult but people like Bert Williams pulled it off.

Any good clean joke was a diamond and was likely to be stolen.

Many a comic found that other performers had done his material in various towns.

Early radio and television would rely on the same jokes.

Indeed, you still hear some of those jokes today.

I know how you sleep . . . like a baby. You cry a little, then wet the bed a little.

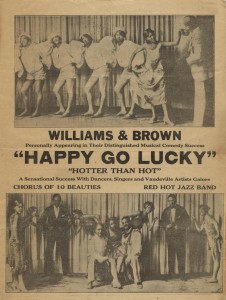

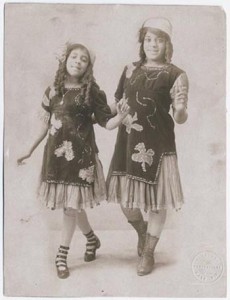

The Duncan Sisters did a musical act as “Topsy and Eva,” characters from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. They sang and played various instruments with limited skill but tremendous charm, pleasing fans for decades.

He hands out color photographs of two bottles of well-known household products, asking, “Have you seen my Pride and Joy?”

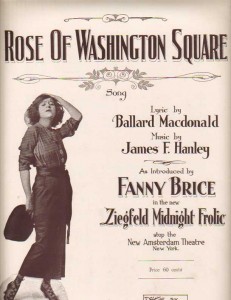

Elsie Janis sang and clowned her way to stardom in vaudeville and musical comedy before winding up a successful Hollywood screenwriter and lyricist.

That’s the last time I steal a joke from Berle.

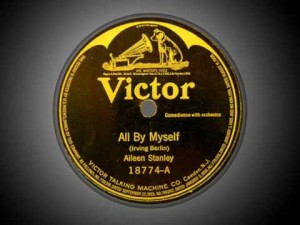

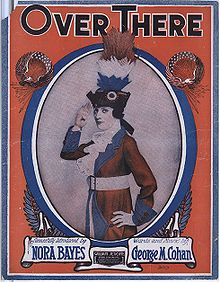

Nora Bayes was the well dressed soprano who made “Shine On Harvest Moon” a hit.

Her fans followed her scandalous marriages, most memorably to songwriter Jack Norworth (composer of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”)

Nora Bayes was one of America’s first singers to attain national popularity.

I saw a man lying in the street. I said, “Can I help you?” He said, “No, I found this parking place and I sent my wife out to buy a car.

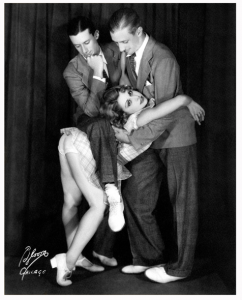

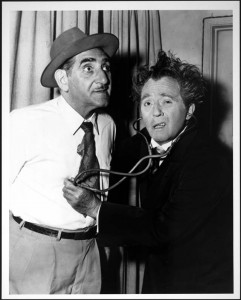

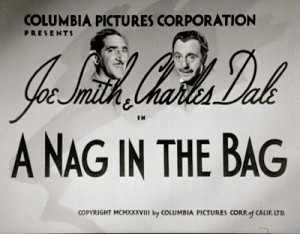

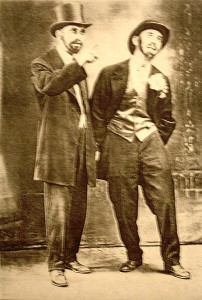

Smith and Dale were one of vaudeville’s most popular comedy teams.

They were together for seventy-five years and they supposedly hated each other the whole time. This is not that difficult to believe.

Neil Simon’s The Sunshine Boys was based on Smith and Dale’s relationship.

Their routines were corny but funny, relying on slapstick gags and carefully timed dialogue.

I don’t want to say that business was bad at the last place I played, but when a fellow called up and asked what time is the next show, I said, “When can you make it?”

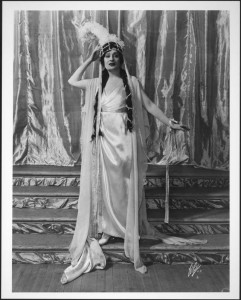

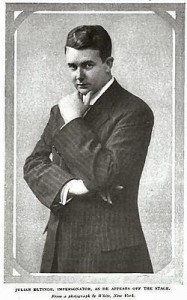

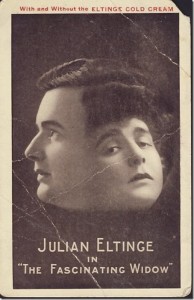

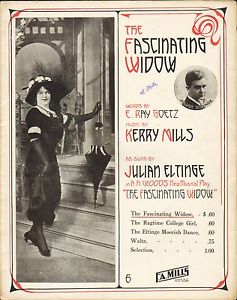

Julian Eltinge was vaudeville’s most famous female impersonator.

Eltinge’s lavish gowns and deft mimicry of feminine behavior made him a longtime favorite.

His fame faded with vaudeville, and he found few engagements in his later years.

Julian Eltinge was in The Fascinating Widow (1911).

He was the only drag performer to have a Broadway theatre named after him. The Eltinge later became the Empire, and its old façade and lobby are now part of the AMC Multiplex on 42nd Street.

Other female impersonators with outstanding vaudeville careers include the campy Bert Savoy.

There was also Karyl Norman.

My brother-in-law saw a sign that said ‘Drink Canada Dry,’ so he did.

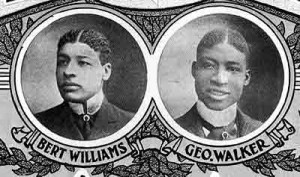

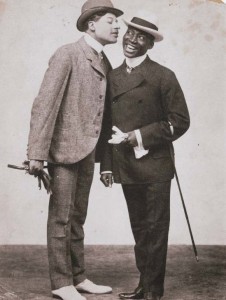

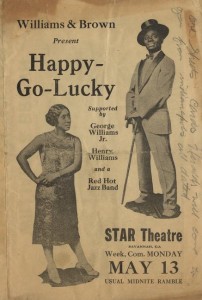

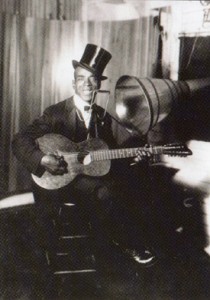

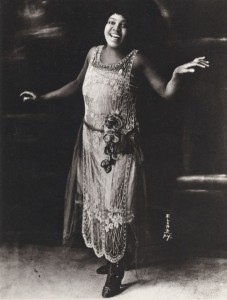

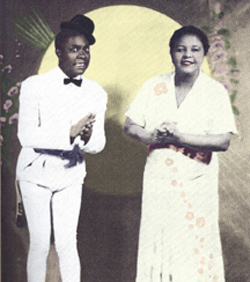

Bert Williams was the first black performer to gain national stardom in the US, with comic gems like the song “Nobody.”

After partnering with George Walker in vaudeville and musical comedy, Williams went on to solo success in vaudeville and starred in several editions of the Ziegfeld Follies.

Despite his tremendous popularity, Williams was often subjected to blind bigotry. When a bartender in a first class Chicago hotel told him that drinks for “coloreds” were $50 each, Williams pulled out a wad of fifties and ordered the man to pour a round for everyone at the bar.

Doc, it hurts when I go like that. Doc: Don’t go like that.

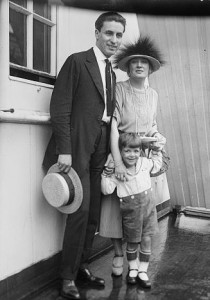

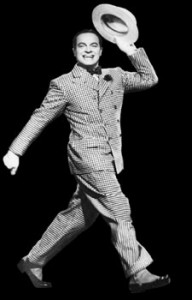

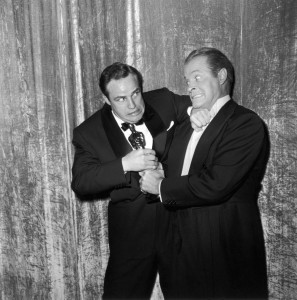

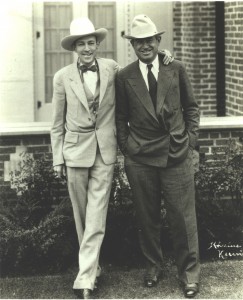

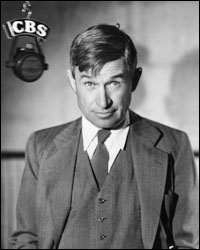

Leslie Townes Hope (May 29, 1903 – July 27, 2003), was an English-born American comedian, vaudevillian, actor, singer, dancer, author, and athlete who appeared on Broadway, in vaudeville.

What do you get when you cross a rooster and a duck?

A bird who gets up at the quack of dawn.

Hope’s English father, William Henry Hope, was a stonemason from Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, and his Welsh mother, Avis Townes, was a light-opera singer from Barry who later worked as a cleaning woman. She married William Hope in April 1891 and the couple lived at 12 Greenwood Street in the town, then moved to Whitehall and St George in Bristol.

In 1908 the Hope family emigrated to the United States aboard the SS Philadelphia, and passed inspection at Ellis Island on March 30, 1908, before moving to Cleveland, Ohio.

From the age of 12, Bob Hope earned pocket money by busking (frequently on the streetcar to Luna Park), singing, dancing, and performing comedy patter.

He entered many dancing and amateur talent contests (as Lester Hope), and won a prize in 1915 for his impersonation of Charlie Chaplin.

Hope worked as a butcher’s assistant and a lineman in his teens and early twenties.

He and his girlfriend, Millie Rosequist, signed up for dance lessons.

Encouraged after they performed in a three-day engagement at a club, Hope then formed a partnership with Lloyd Durbin, a fellow pupil from the dance school.

Silent film comedian Fatty Arbuckle saw them perform in 1925 and obtained them steady work with a touring troupe called Hurley’s Jolly Follies.

Within a year, Hope had formed an act called the Dancemedians with George Byrne and the Hilton Sisters, conjoined twins who performed a tap dancing routine on the vaudeville circuit.

Hope and Byrne had an act as a pair of Siamese twins as well, and danced and sang while wearing blackface, before friends advised Hope that he was funnier as himself.

In 1929, he changed his first name to “Bob”. In one version of the story, he named himself after racecar driver Bob Burman. In another, he said he chose Bob because he wanted a name with a friendly “Hiya, fellas!” sound to it.

After five years doing vaudeville, Hope was very surprised when he failed a 1930 screen test for the French film production company Pathé at Culver City, California.

Bob Hope began performing on the radio in 1934 and switched to television when that medium became popular in the 1950s. He began doing regular TV specials in 1954, and hosted the Academy Awards fourteen times in the period from 1941 to 1978.

Bob’s first film was the comedy, Going Spanish (1934). He was not happy with the film, and told Walter Winchell, “When they catch John Dillinger, they’re going to make him sit through it twice.”

Hope moved to Hollywood when Paramount Pictures signed him for the 1938 film The Big Broadcast of 1938, also starring W.C. Fields. The song Thanks For The Memory, which later became his trademark, was introduced in this film as a duet with Shirley Ross and accompanied by Shep Fields and his orchestra.

Bob Hope was best known for comedies like My Favorite Brunette and the highly successful Road movies in which he starred with Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour. The series consists of seven films made between 1940 and 1962.

Hope had seen Lamour as a nightclub singer in New York, and invited her to work on his United Service Organizations (USO) tours.

Dorothy Lamour sometimes arrived for filming prepared with her lines, only to be baffled by completely re-written scripts or ad-lib dialogue between Hope and Crosby.

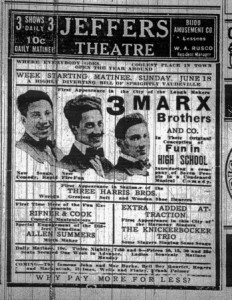

One is reminded here of Margaret Dumont in the Marx Brothers films. She never quite understood their routines.

Hope and Lamour were lifelong friends, and she remains the actress most associated with his film career.

On July 27, 2003, two months after his 100th birthday, Bob Hope died at his home in Toluca Lake, Los Angeles. His grandson, Zach Hope, told Soledad O’Brien that when asked on his deathbed where he wanted to be buried, Hope replied, “Surprise me.”

WOMAN: Someone is fooling with my knee. MAN: It’s me, and I’m not fooling!

Vaudeville’s audiences, as well as many of its stars, were drawn from the newly immigrated working classes.

Just as goods in the late 19th century could be manufactured in a central location and shipped throughout the country, successful vaudeville routines and tours were first established in New York and other large cities and would then be booked on a tour lasting for months.

The act would change little as it was performed throughout the United States, so vaudeville was a precursor of mass media — a means of creating and sharing a national culture.

Vaudeville’s influence on most popular entertainment forms of the 20th century — musical comedy, motion pictures, music, radio, television — was pervasive.

WOMAN: I’m not married.

MAN: Any children?

WOMAN: I told you, I’m not married.

MAN: Answer my question!

The word “vaudeville” may come from the expression voix de ville which means “voice of the city” or “songs of the town.”

Or, the term may come from a collection of fifteenth-century satirical songs by Olivier Basselin, “Vaux de Vire.”

Then again, the word vaudeville may derive from the Vau de Vire, a valley in Normandy noted for its style of satirical songs with topical themes.

Vaudeville, referring specifically to North American variety entertainment, came into common usage after 1871, with the formation of Sargent’s Great Vaudeville Company of Louisville, Kentucky.

CISSIE: She never married, did she? MARIE: No, her children wouldn’t let her.

Though the word “vaudeville” had been used in the US as early as the 1830s, most variety theatres adopted the term in the late 1880s and early 1890s for two reasons. First, they wished to distance themselves from the earlier rowdy, working-class variety halls.

Second, the supposedly French term vaudeville lent an air of sophistication.

Many people preferred the earlier term “variety” to what manager Tony Pastor called vaudeville’s “sissy and Frenchified” successor.

Thus, vaudeville was marketed as “variety” well into the 20th century.

Injured Man crosses stage in assorted bandages and casts.

Comic: What happened to you?

Injured Man: I was living the life of Riley.

Comic: And?

Injured Man: Riley came home!

A descendant of variety, (c. 1860s–1881), vaudeville was distinguished from the earlier form by its mixed-gender audience, usually alcohol-free halls, and often slavish devotion to respectability among members of the middle class.

The form gradually evolved from the concert saloon and variety hall into its mature form throughout the 1870s and 1880s.

This more genteel form was known as “Polite Vaudeville.”

Man at Desk: (picks up phone) Hello, Cohen, Cohen, Cohen and Cohen.

Caller: Let me speak to Mr. Cohen.

Man at Desk: He’s dead these six years. We keep his name on the door out of respect.

Caller: Then let me speak to Mr. Cohen.

Man: He’s on vacation.

Caller: (Exasperated) Well then, let me speak to Mr. Cohen.

Man: He’s out to lunch.

Caller: (Yells) Then let me speak to Mr. Cohen!

Man: Speaking.

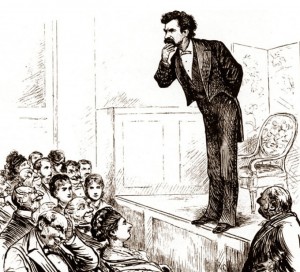

In the years before the American Civil War, entertainment existed on a different scale.

Variety theatre existed before 1860 in Europe and elsewhere.

In the US, as early as the first decades of the 19th century, theatregoers could enjoy a performance consisting of Shakespeare plays, acrobatics, singing, dancing, and comedy.

There were even Chataquas where people could enjoy a slide presentation and lectures by eminent authorities on various subjects.

Indeed, Mark Twain was a part of this circuit.

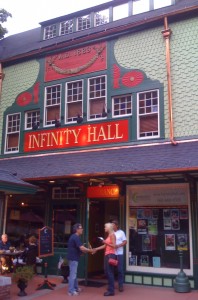

When Big Brother and the Holding Company played the Infinity Hall in Connecticut, Ben Nieves and I visited the little room where Twain waited to go on.

Vaudeville was characterized by traveling companies touring through cities and towns.

Jerk – audience member

Yock – a belly laugh

Skull – make a funny face

Talking woman – delivers lines in comedy skits

Cover – perform someone’s scenes for them

The asbestos is down – the audience is ignoring the jokes

From hunger – a lousy performer

Mountaineer – a new comic, fresh from the Catskill resort circuit

Boston version – a cleaned-up routine

Blisters – a stripper’s breasts

Cheeks – a stripper’s backside

Gadget – a G-string

Trailer – the strut taken before a strip

Quiver – shake the bust

Shimmy – Shake the posterior

Bump – swing the hips forward

Grind – full circle swing of the pelvis

Milk it – get an audience to demand encores

Brush your teeth! – comedian’s response to a Bronx cheer

Circuses regularly toured the country, dime museums appealed to the curious, amusement parks, riverboats, and town halls often featured “cleaner” presentations of variety entertainment, and saloons, music halls and burlesque houses catered to those with a taste for the risqué.

In the 1840s, the minstrel show, another type of variety performance, and “the first emanation of a pervasive and purely American mass culture,” grew to enormous popularity and formed what Nick Tosches called “the heart of 19th-century show business.”

Blaze tripped to the microphone. Looking down at her exposed breast, she said, “What are you doing out there, you gorgeous thing?” Then she covered herself. “You got to tell them they’re pretty,” she said; “it makes them grow” . . . Then she flung herself on the couch and quickly stripped down to a transparent bra and black garter pants. She produced a power puff and asked rhetorically, “Who’s going to powder my butt?”

A significant influence also came from Dutch ministrels and comedians.

Medicine shows traveled the countryside offering programs of comedy, music, jugglers and other novelties along with displays of tonics, salves, and miracle elixirs.

“Wild West” shows provided romantic vistas of the disappearing frontier, complete with trick riding, music and drama. Vaudeville incorporated these various itinerant amusements into a stable, institutionalized form centered in America’s growing urban hubs.

WEBER: I am delightfulness to meet you! FIELDS: Der disgust is all mine!

In the early 1880s, impresario Tony Pastor, a circus ringmaster turned theatre manager, capitalized on middle class sensibilities and spending power when he began to feature “polite” variety programs in several of his Gotham City theatres.

The usual date given for the “birth” of vaudeville is October 24, 1881 at New York’s Fourteenth Street Theater, when Pastor famously staged the first bill of self-proclaimed “clean” vaudeville in New York City.

Hoping to draw a potential audience from female and family-based shopping traffic uptown, Pastor barred the sale of liquor in his theatres, eliminated bawdy material from his shows, and offered gifts of coal and hams to attendees.

Yes, folks, Fourteenth Street was uptown in the 1880s.

Pastor’s experiment proved successful, and other managers soon followed suit.

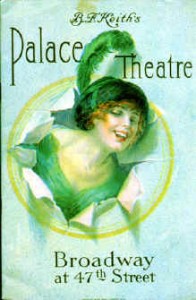

B. F. Keith took the next step, starting in Boston, where he built an empire of theatres and brought vaudeville to the US and Canada.

Later, E.F. Albee, adoptive grandfather of the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Edward Albee, managed the chain to its greatest success.

Circuits such as those managed by Keith-Albee provided vaudeville’s greatest economic innovation and the principal source of its industrial strength.

They enabled a chain of allied vaudeville houses that remedied the chaos of the single-theatre booking system by contracting acts for regional and national tours. These could easily be lengthened from a few weeks to two years.

Albee also gave national prominence to vaudeville’s trumpeting “polite” entertainment, a commitment to entertainment equally inoffensive to men, women and children.

Acts that violated this ethos (ones which used words such as “hell”) were admonished and threatened with expulsion from the week’s remaining performances or were canceled altogether.

In spite of such threats, performers routinely flouted this censorship, often, of course, to the delight of the very audience members whose sensibilities were supposedly endangered.

E.F. Albee eventually instituted a set of guidelines for audience members at his show, and these were reinforced by the ushers working in the theater.

Thus “polite entertainment” also extended to B.F. Keith’s company members.

Albee went to extreme measures to maintain this level of modesty.

Keith even went as far as posting warnings backstage such as this: “Don’t say ‘slob’ or ‘son of a gun’ or ‘hully gee’ on the stage unless you want to be canceled peremptorily…if you are guilty of uttering anything sacrilegious or even suggestive you will be immediately closed and will never again be allowed in a theater where Mr. Keith is in authority.”

Along these same lines of discipline, Keith’s theater managers would occasionally send out blue envelopes with orders to omit certain suggestive lines of songs and possible substitutions for those words. This is the origin of the word ‘blue’ to describe off color material.

If actors chose to ignore these orders or quit, they would get “a black mark” on their name and would never again be allowed to work on the Keith Circuit.

Thus, actors learned to follow the instructions given them by B.F. Keith for fear of losing their careers forever.

By the late 1890s, vaudeville had large circuits, houses (small and large) in almost every sizable location, standardized booking, broad pools of skilled acts, and a loyal national following.

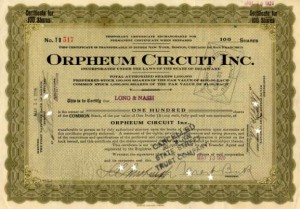

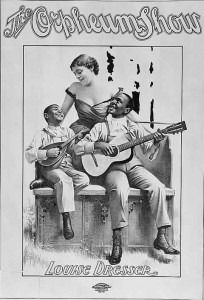

One of the biggest circuits was Martin Beck’s Orpheum Circuit. It incorporated in 1919 and brought together 45 vaudeville theaters in 36 cities throughout the US and Canada and a large interest in two vaudeville circuits.

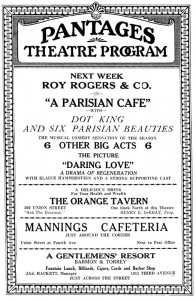

Another major circuit was that of Alexander Pantages. At its hey-day Pantages owned more than 30 vaudeville theaters and controlled, through management contracts, perhaps 60 more in both the US and Canada.

Vaudeville was truly democratic. It played across multiple strata of economic class and auditorium size. On the vaudeville circuit, it was said that if an act would succeed in Peoria, Illinois, it would work anywhere. The question “Will it play in Peoria?” has now become a metaphor for whether something appeals to the American mainstream public.

The three most common levels were the “small time” (lower-paying contracts for more frequent performances in rougher, often converted theatres), the “medium time” (moderate wages for two performances each day in purpose-built theatres), and the “big time” (possible remuneration of several thousand dollars per week in large, urban theatres largely patronized by the middle and upper-middle classes).

As performers rose in renown and established regional and national followings, they worked their way into the less arduous working conditions and better pay of the big time.

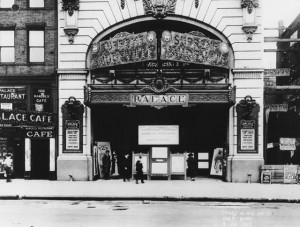

The capitol of the big time was New York City’s Palace Theatre (or just “The Palace” in vaudevillian slang), built by Martin Beck in 1913 and operated by B.F. Keith.

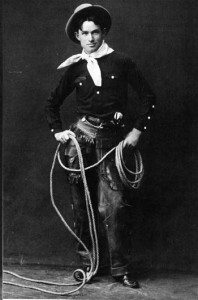

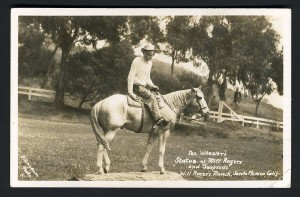

The Palace had many inventive novelty acts, national celebrities, and acknowledged masters of vaudeville performance, such as writer, comedian and trick roper Will Rogers.

The money was all appropriated for the top in the hopes that it would trickle down to the needy. Mr. Hoover didn’t know that the money trickled up. Give it to the people at the bottom and the people at the top will have it before night, anyhow. But it will at least have passed through the poor fellow’s hands.

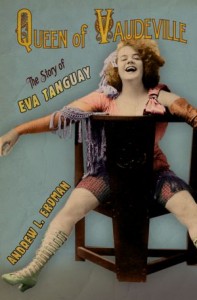

Andrew Erdman’s book Blue Vaudeville notes that the Vaudeville stage was marked with descriptions like, “a highly sexualized space…where unclad bodies, provocative dancers, and singers of ‘blue’ lyrics all vied for attention.”

I am not a member of an organized political party. I am a Democrat.

The Palace was the career apex f0r many a vaudevillian.

When I die, my epitaph, or whatever you call those signs on gravestones, is going to read: “I joked about every prominent man of my time, but I never met a man I dident (sic) like.” I am so proud of that, I can hardly wait to die so it can be carved.

A vaudeville show at the Palace would begin with a sketch, follow with a single – an individual male or female performer, next would be an alley oop – an acrobatic act, then another single, followed by yet another sketch such as a blackface comedy.

The taxpayers are sending congressmen on expensive trips abroad. It might be worth it except they keep coming back.

What followed for the rest of the show would vary from musicals to jugglers to song and dance singles and end with a final extravaganza – either musical or drama – with the full company.

Lord, the money we spend on Government! And it’s not one bit better than the government we got for one-third the money twenty years ago.

These shows would feature such stars as Eubie Blake – the piano player, the famous and magical Harry Houdini and child star, Baby Rose Marie.

Democrats never agree on anything, that’s why they’re Democrats. If they agreed with each other, they would be Republicans.

It is said that at any given time, Vaudeville was employing over twelve thousand different people throughout its entire industry. Each entertainer would be on the road 42 weeks at a time while working a particular “Circuit” – or an individual theatre chain of a major company.

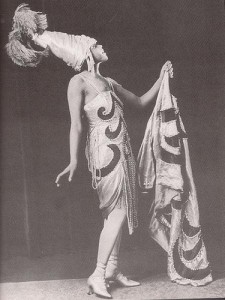

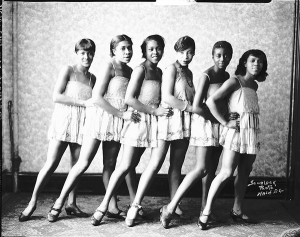

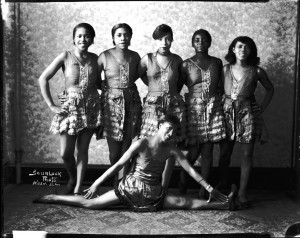

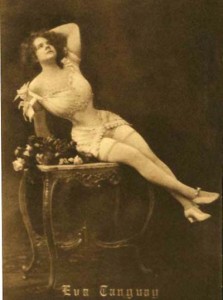

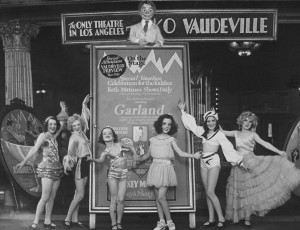

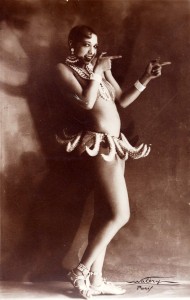

Vaudeville showed an increasing interest in the female figure.

Even if you’re on the right track, you’ll get run over if you just sit there.

Vaudeville highlighted and objectified the female body as a “sexual delight,” a phenomenon that historians believe emerged in the mid-19th century.

I can remember way back when a liberal was generous with his own money.

Vaudeville marked a time in which the female body became its own “sexual spectacle” more than it ever had before.

You can’t tell what a man is like or what he is thinking when you’re looking at him. You must get around behind him and see what he’s been looking at.

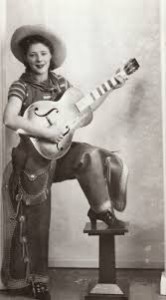

Even acts that were as innocent as a sister act were higher sellers than a good brother act.

It isn’t what we know that gives us trouble, it’s what we know that ain’t so.

Vaudeville performers such as Julie Mackey and Gibson’s Bathing Girls began to focus less on talent and more on physical appeal through their figure, tight gowns, and other revealing attire.

This would be a great world to dance in if we didn’t have to pay the fiddler.

It eventually came as a surprise to audience members when such beautiful women actually possessed talent in addition to their appealing looks. This element of surprise colored much of the reaction to the female entertainment of this time.

A remeark generally hurts in proportion to its truth.

The continued growth of the lower-priced cinema in the early 1910s dealt the heaviest blow to vaudeville.

A difference of opinion is what makes horse races and missionaries.

The same thing happened to cinema when television came along.

Everything is funny as long as it is happening to somebody else.

Cinema was first regularly commercially presented in the US in vaudeville halls. The first public showing of movies projected on a screen took place at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall in 1896.

Good judgment comes from experience, and a lot of that comes from bad judgment.

Al Jolson, W.C. Fields, Mae West, Buster Keaton, the Marx Brothers, Jimmy Durante, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Edgar Bergen, Fanny Brice, Burns and Allen and Eddie Cantor, to name a few, used their vaudeville status to vault into the new medium of cinema.

I have a scheme for stopping war. It’s this– no nation is allowed to enter a war till they have paid for the last one.

These former vaudeville performers often exhausted in a few moments of screen time the novelty of an act that might have kept them on tour for several years.

If you find the right job, you’ll never have to work a day in your life.

Jack Benny, Abbot and Costelle, Kate Smith, Cary Grant, Milton Berle, Judy Garland, Rose Marie, Sammy Davis, Jr. Red Skelton and The Three Stooges used vaudeville only as a launching pad for later careers. They left live performance before achieving the national celebrity of earlier vaudeville stars, and found fame in new venues.

Why go out on a limb? That’s where the fruit is.

The line between live and filmed performances was blurred by the number of vaudeville entrepreneurs who made more or less successful forays into the movie business.

I bet after seeing us, George Washington would sue us for calling him father.

Alexander Pantages quickly realized the importance of motion pictures as a form of entertainment. He incorporated them in his shows as early as 1902. Later, he entered into partnership with the Famous Players-Lasky, a major Hollywood production company and an affiliate of Paramount Pictures.

If stupidity got us into this mess, then why can’t it get us out?

By the late 1920s, almost no vaudeville bill failed to include a healthy selection of cinema.

Top vaudeville stars filmed their acts for one-time pay-offs, inadvertently helping to speed the death of vaudeville.

After all, when “small time” theatres could offer “big time” performers on screen at a nickel a seat, who could ask audiences to pay higher amounts for less impressive live talent?

The newly-formed RKO studios took over the famed Orpheum vaudeville circuit and swiftly turned it into a chain of full-time movie theaters.

The half-century tradition of vaudeville was effectively wiped out within less than four years.

Managers further trimmed costs by eliminating the last of the live performances.

Following the greater availability of inexpensive receiver sets later in the decade, radio contributed to vaudeville’s swift decline.

Even the most optimistic people in vaudeville could see the writing, or rather the motion picture, on the wall. The perceptive knew that the death rattle was terminal.

Standardized film distribution and talking pictures of the 1930s were the end of vaudeville.

Live in such a way that you would not be ashamed to sell your parrot to the town gossip.

By 1930, the vast majority of formerly live theatres had been wired for sound, and none of the major studios was producing silent pictures.

For a time, the most luxurious theatres continued to offer live entertainment, but most theatres were forced by the hard times in the 1930s to economize.

There was no abrupt end to vaudeville, though the form was clearly sagging by the late 1920s.

The Palace Theatre in New York changed to an exclusively cinematic format on November 16, 1932. No other single event was more of a death knell for vaudeville.

Though talk of vaudeville’s resurrection was heard during the 1930s and later, the demise of the supporting apparatus of the circuits and the higher cost of live performance made any large-scale renewal of vaudeville unrealistic.

The most striking examples of Gilded Age theatre architecture were commissioned by the big time vaudeville magnates and stood as monuments of their wealth and ambition. Examples of such architecture are the theaters built by impresario Alexander Pantages, who often used architect B. Marcus Priteca (1881–1971), who in turn regularly worked with muralist Anthony Heinsbergen. Priteca devised an exotic, neo-classical style that his employer called “Pantages Greek”.

Though classic vaudeville reached a zenith of capitalization and sophistication in urban areas dominated by national chains and commodious theatres, small-time vaudeville included countless more intimate and locally controlled houses. Small-time houses were often converted saloons, rough-hewn theatres or multi-purpose halls, together catering to a wide range of clientele. Many small towns had purpose-built theatres.

Vaudeville was not wiped out by silent films. Many managers featured “flickers” at the end of their bills, finding them cheaper than the live closing acts that audiences walked out on anyway.

Top screen stars made lucrative personal appearance tours on the big time circuits. So what killed vaudeville? The most truthful answer is that the public’s tastes changed and vaudeville’s managers (and most of its performers) failed to adjust to those changes.

In the mid-1920s, when everyone knew vaudeville was in danger, E.F. Albee set expensive new production requirements which strained performers and made it harder for most houses to turn a profit.

When well dressed comics entertained between numbers in place of an energetic slapstick act, vaudeville lost of a lot of its verve.

Cycloramas, drapery and gorgeous scenery added to the beauty of the show, but not to its comedy.

According to Variety, by the end of 1926 only a dozen “big time” vaudeville houses remained – the rest had converted to film use.

In December 1927, no less a star than Julian Eltinge proclaimed in Variety that vaudeville was “shot to pieces,” and was no longer able to attract “big names.”

The success of talking films in the late 1920s sharpened the sense of crisis in vaudeville circles.

In 1929, Albee replaced the Orpheum circuit’s two performance-a-day format with a crushing five-a-day policy.

This only succeeded in exhausting performers and depleting the supply of fresh material.

At the same time, risqué or “blue” material was allowed in major acts, offending many in vaudeville’s family-oriented audience.

Albee hammered another nail into vaudeville’s coffin when he partnered with Joseph P. Kennedy’s Hollywood film company in 1928 to form Radio Keith Orpheum (RKO) Studios.

Kennedy wrangled control of the new organization from Albee, turning the glorious Orpheum circuit into a chain of movie houses. In October of 1929, Variety figured that there were only six full-time vaudeville houses still operating, with as many as three hundred theatres offering a bill of acts between feature films.

It was extraordinary how the public had changed. They had become very blasé about entertainment. Whereas American used to arrange to spend an evening in the theatre for a treat, now they seemed to go to the theater just to kill time.

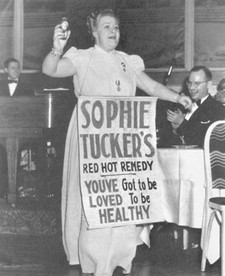

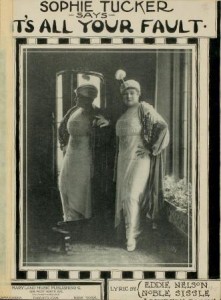

The theaters were full of children, noted Sophie Tucker. At the first two shows in the afternoon the house would be full of boys and girls, slumped down in their seats, obviously bored with the acts and only waiting for the picture to come on. Kids and necking couples.

By the time of the last show, at 9:30 PM, when you had your best audience, you were dead tired. Too tired to care whether they liked you or not.

Sophie Tucker kept on performing. Sophie was a hero in more ways than one.

She was headlining at New York’s Palace Theater in February 1932 when a fire broke out backstage. To prevent panic, Tucker remained onstage to coax the audience out of the theatre – despite the sparks that threatened to ignite her flammable sequined gown.

The Palace soon reopened, but by that November it became a full-time movie theatre.

The Palace’s first feature film was The Kid From Spain – starring vaudeville veteran Eddie Cantor. Live acts appeared between screenings, but were dropped as of 1935.

Although many theatres still presented vaudeville acts between films, the number of available gigs kept shrinking.

A few vaudeville theaters managed to hold out. I have mentioned before that I saw a vaudeville show on Market Street in San Francisco when I was six or seven.

New York City’s State Theatre at Broadway and 45th Street continued to present four-a-day bills until December 23, 1947.

The final bill included comedian Jack Carter and Yiddish theatre legend Molly Picon. At the closing performance, veteran vaudevillian George Jessel, who eulogized many show biz greats, came on stage and said “I heard vaudeville is finished here tonight, so I thought I’d drop in and tell you folks that talent can never die.”

It’s true, talent will never die, but it can move somewhere else.

There have been numerous attempts to revive vaudeville – a hopeless task, given the changes in American popular culture.

The last live echo of vaudeville was Radio City Music Hall, which kept the presentation house format alive until economics forced it to become a concert venue in 1979.

Some lucky vaudeville singers and comics found a new home on radio, where “variety shows” offered something like audio vaudeville.

Even silent acts (jugglers, animal acts, etc.) found work on television, where variety shows remained popular for several decades.

Ed Sullivan’s television show was pure vaudeville. I was on that show with Big Brother and the Holding Company, so I can say I have done vaudeville.

Carol Burnett’s Broadway-style reviews had the family-friendly spirit of big time vaudeville.

The talk shows carried on the legacy of the Chatauqua side of vaudeville. Janis and I were on Dick Cavett. He was very fond of her, let’s put it that way.

See you next week?

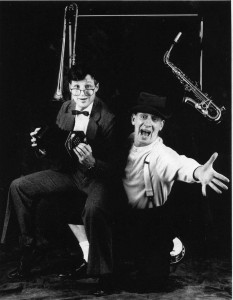

Peter Albin and Sam Andrew still doing vaudeville.

_______________________________________________

Great review

Have been considering bringing some of these old live performers back to a once small town vaudaville stage.

The Opera House was build in 1908…It is now a venue for

weddings and banquets…seats 150 people at tables…

Always looking for advice..see: Operahouseofpacific.com

Jim McHugh