These are some of my tools:

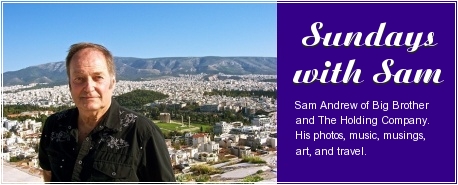

When I go on the road with Big Brother and the Holding Company I take a set of pencils along and sketch in the mornings.

Winsor & Newton brushes, although I’ll use anything that feels right, even a twig torn off a tree, which I have used many times.

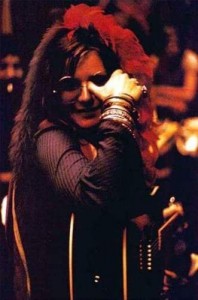

A Gibson Hummingbird guitar that Janis gave me. I use it for jazz mostly. It has a beautiful singing treble and a big throated bass.

Jim Dunlop guitar pick, two millimeters thick. Takes a lot to wear one out.

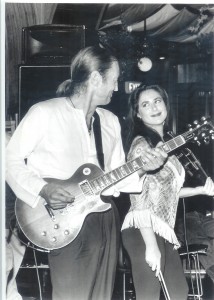

Gibson Les Paul, easy to play, good sustain, shhh, can you hear it?

Paul Reed Smith gave me this guitar. I love it.

I have several of these snail-like tuners. They cost about $ 20 apiece. I can put two or three in my pocket. They replace a tuner that I used, but did not own, in the 1960s. It was a Hammond Strobo-Con and it sold for about $ 450 in 1960s money ($ 4,500 today?). It was larger than a shoebox, it had pretty purple lights and it was really an oscilloscope.

Shortly after the oscilloscope experience came a tuner that you could plug into the amp and it would emit a constant and annoying A 440. We used that for a while. We were a string band, like a string quartet, so our tuning wandered, did it ever.

Mesa Boogie Subway Rocket, tiny and terrific.

I have other tools: Books, books under the couch, on the floor, on my desk, in the bathroom, some even in bookcases, on the kitchen table, in the car, in my bag, on my night table, in the bed, under the bed, in the closet, everywhere.

And let’s not forget this computer. It’s organic.

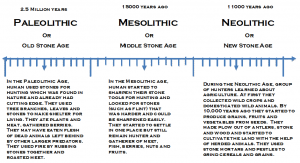

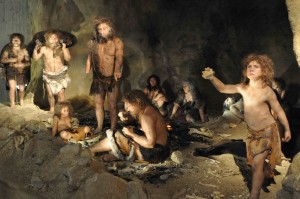

There are two stages of prehistory, the Paleolithic which began about two million years ago, and then the Neolithic which took hold in the Near East (Mesopotamia) about 10,000 BCE.

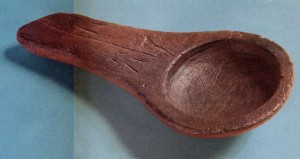

The tools of the Paleolithic were very basic, of course, and mostly used for food gathering.

Neolithic tools were much more complex stone instruments used for agriculture and building.

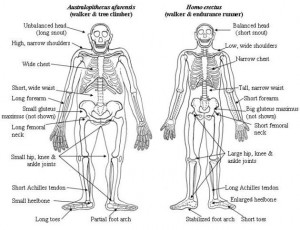

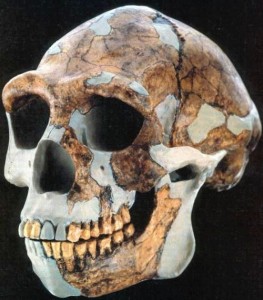

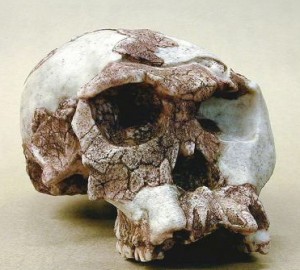

Homo Sapiens was first in evidence about 500,000 years ago and before that there was Homo Erectus, a very successful tool making species which arose about two million years ago, who learned to make fire.

Homo Erectus

Homo Habilis (handy man), the first species of human being, coexisted with hominids such as Paranthropus and Australopithecus afarensis (Lucy).

Making tools and teaching the making of tools to others is practiced in all human societies.

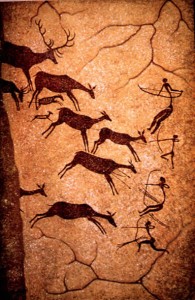

In the Upper Paleolithic, about 30,000 years ago, people began to make bows and arrows and spear throwers. They domesticated the wolf.

They made beautiful paintings on the walls of caves like Chauvet.

Paintings with as developed a sense of perspective, shading and drama as we can make today, and they did them 35,000 years ago.

They did their painting in the dark. Well, maybe they used a hollowed out stone, poured in some animal fat and made a wick out of hemp or some other fiber. That’s not that much light, though, there underground far from the cave’s mouth. Seventy of these lamps, in all shapes and sizes, were found on the floor of Lascaux.

Neanderthals, who had bigger brains than we do, but who were not as tall, took care of their old and infirm and they buried their dead.

There was even something of a cult of the dead in the Middle Paleolithic (100,000 – 50,000 years ago).

Neanderthals were most likely absorbed into Homo Sapiens populations such as the Cro-Magnons.

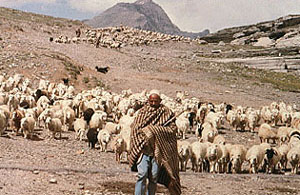

Around 10,000 BCE, a surprising thing happened. In different parts of the world, parts that had no way of communicating with each other, people began to hit on the idea of growing their food and domesticating animals. In the Near East, India, Africa, North Asia, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America this Neolithic Revolution fundamentally changed peoples’ lives.

This Revolution took two different roads: one went from gathering food to growing it, to plowing the fields.

The other path out of the Paleolithic went from hunting to herding and led to pastoral nomadism.

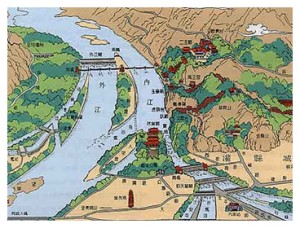

Where there was enough water, particularly in great river areas, agriculture prevailed.

Where the land was too dry for farming, people kept herds of animals and led a nomadic life. Finding timberland for sale was not as easy as it is today either.

Mongols, Bedouins, the Sami (Lapp) people who still follow the reindeer, the people in the New World who domesticated llamas, all are examples of people who descended from hunters, not gatherers.

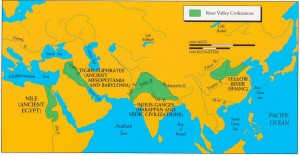

The people who settled in the great river valleys, the Nile, Mesopotamia (which means “in the middle of rivers”), the Indus-Ganges valley, the Yellow River valley, the Ohio Mississippi valley planted crops, were stable from year to year, formulated laws and customs and social classes, built cities, invented writing systems.

Civilization is all about water.

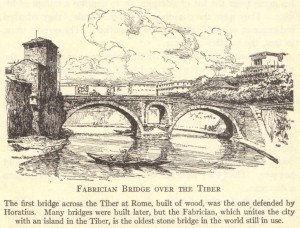

The Romans settled by the Tiber in the center of Italy.

They were the master engineers of the ancient world.

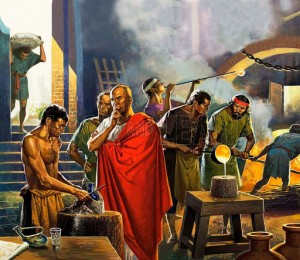

Technology is the world of farming, weaving, potting, building, transporting, healing, governing and, let’s not forget, glassmaking.

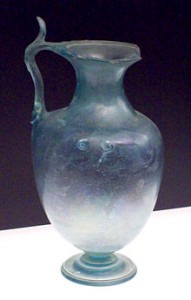

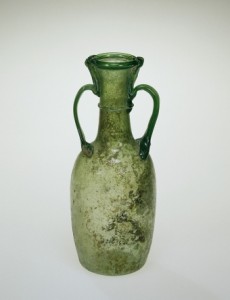

Glass objects have been recovered across the Roman Empire in domestic, industrial and funerary contexts. Glass was used mainly in vessels, although mosaic tiles and window glass were also produced. This is beach sand, the main ingredient in Roman glass.

Roman glass production developed from late Greek technical traditions, and was about the making of intensely colored cast glass vessels.

During the 1st century CE there was rapid technical growth in glassmaking and glass blowing. Colorless or ‘aqua’ glasses were important at this time.

Production of raw glass was begun in one place and finished in another, and by the end of the 1st century CE large scale manufacturing resulted in the establishment of glass as a commonly available material in the Roman world, from everyday glass to technically very difficult specialized types of luxury products, which must have been very expensive.

At the beginning of the 1st century CE there was still no Latin word for glass. Vitrum came to be used and is the word that passed down into the Romance languages.

Glassmaking was a relatively minor craft during the Republican period (6th to 1st centuries BCE), although, during the early decades of the 1st century CE the quantity and diversity of glass vessels available increased dramatically.

This was a direct result of the massive growth of the Roman influence at the end of the Republican period, the Pax Romana that followed the decades of civil war, and the stability that occurred under Augustus.

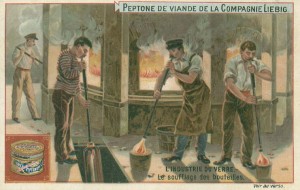

Glassblowing, a major new technique in glass production which had been introduced during the 1st century CE. allowed glass workers to produce vessels with considerably thinner walls, decreasing the amount of glass needed for each vessel. Glass blowing was also considerably quicker than other techniques, and vessels required considerably less finishing, representing a further saving in time, raw material and equipment.

Although earlier techniques dominated during the early Augustan and Julio-Claudian periods, by the middle to late 1st century CE these techniques had been largely abandoned in favor of blowing the glass into shape.

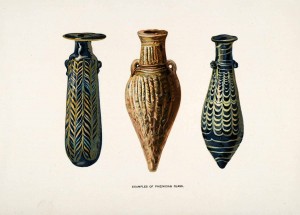

Glassblowing is a glass forming technique which was invented by the Phoenicians around 50 BCE somewhere along the Syro-Palestinian coast.

The concentration of natron, which acts as a flux in glass, is slightly lower in blown vessels than those manufactured by casting. Lower concentration of natron allowed the glass to be stiffer for blowing.

The gaffer (glass blower) slowly blows into the tube and inflates the parison, the glass bubble. As it expands, the parison loses heat and becomes solid.

This is one of those beautiful changes in nature where a liquid suddenly becomes solid and is thus frozen forever. Amber, where sap becomes a jewel is one example. Using plaster of Paris where the whole mixture heats and suddenly becomes solid is another. Watching a drop of water almost fall from the eave of a house and then suddenly become solid ice is an example. In ceramics, the artist works with the watery clay which at one point becomes solid and will stay that way forever, which is an alchemy in itself. All of this change from a liquid impermanence to a solid forever lasting is so interesting to watch.

The two major methods of glassblowing are free-blowing and mold-blowing. Free-blowing involves the blowing of short puffs of air into a molten portion of glass (the gather) which has been spooled at one end of the blowpipe. This has the effect of forming an elastic skin on the interior of the glass blob that matches the exterior skin caused by the removal of heat from the furnace. The glassworker can then quickly inflate the molten glass to a coherent blob and work it into a desired shape.

Mold-blowing was an alternate glassblowing method that came after the invention of free-blowing, during the first part of the second quarter of the 1st century CE. A glob of molten glass is placed on the end of the blowpipe, and is then inflated into a wooden or metal carved mold. In this way, the shape and the texture of the bubble of glass is determined by the design on the interior of the mold rather than the skill of the glassworker, although it takes a great deal of skill just to blow this glass into that mold.

Single-piece mold and multi-piece mold were frequently used to produce mold-blown vessels. A single-piece mold allows the finished glass object to be removed in one movement by pulling it upwards from the mold. This method is for producing tableware and utilitarian vessels for storage and transportation.

A multi-piece mold is made in paneled mold segments that join together, thus permitting the development of more sophisticated surface modeling, texture and design.

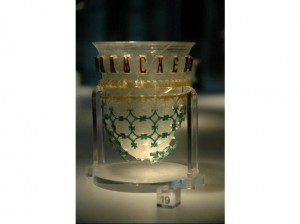

This piece was blown in a three-part mold decorated with the foliage relief frieze of four vertical plants. After the discovery of mold-blown techniques during the Roman era, glass vessels were created and signed by individual makers, such as Ennion, and their superb works were appreciated by the buying public.

Ennion was one of the most prominent glassworkers from Phoenicia (Lebanon). He was renowned for producing the multi-paneled mold-blown glass vessels that were complex in their shapes, arrangement and decorative motifs.

Ennion signed this piece. The complexity of designs of these mold-blown glass vessels documented the sophistication of the glassworkers in the eastern regions of the Roman Empire.

Mold-blown glass vessels manufactured by the workshops of Ennion and other contemporary glassworkers such as Jason, Nikon, Aristeas, and Meges, constitutes some of the earliest evidence of glassblowing found in the eastern territories.

One of the main glassblowing centers of the Roman period was established in Colonia Agrippinensis (Köln Cologne) on the Rhine in the late 1st century BCE. Stone base molds and terracotta base molds were discovered from these Rhineland workshops, suggesting the adoption and the application of mold-blowing technique by the glassworkers.

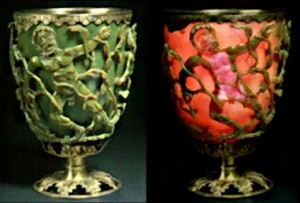

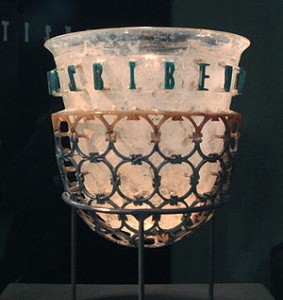

Diatret glass from Köln would usually comprise a colorless glass cup, set in a cage of brightly colored strands of glass. The cage cup (Greek diatreton, also vas diatretum, plural diatreta, or “reticulated cup”) is a type of luxury vessel, found from about the 4th century CE. It is the pinnacle of Roman achievement in glassmaking.

Blown flagons and blown jars decorated with ribbing, as well as blown perfume bottles with letters CCAA or CCA which stand for Colonia Claudia Agrippinensis were also produced in Köln.

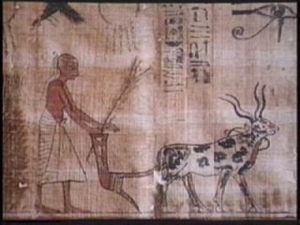

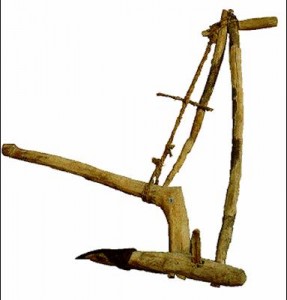

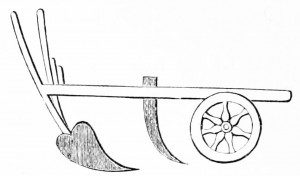

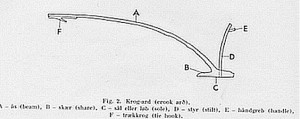

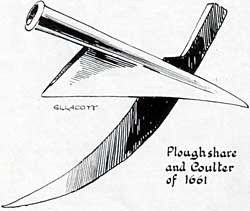

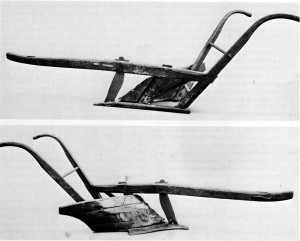

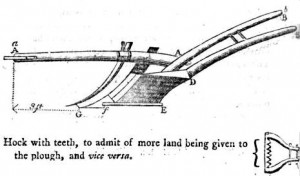

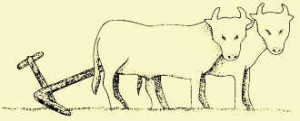

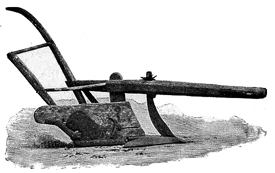

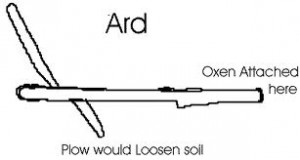

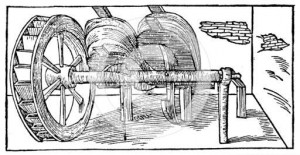

What generated the money to buy these luxuries? Mostly, it was the land, agriculture and the plow (plough). Some of the main parts of the plow are: 1. the handle c. the share (this is the part that digs into the earth). The coulter (4) looks like a knife and coulter means knife. It is the iron knifelike object that first breaks the soil so that the share can turn the earth over. 3. looks like a moldboard (mouldboard) which will turn the soil that the share has delved into, turn it and make it ready to receive the seed.

There is an old saying for peace, “beating our swords into plowshares.”

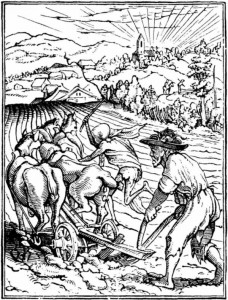

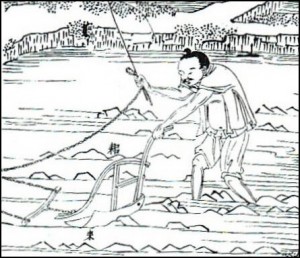

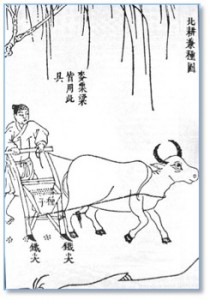

The sole (or slade) is the part of the plow that is flat and lies along the ground to make the furrow wider. Here a man is pouring seed into a funnel that will lead to the sole so that plowing and sowing can be done at the same time. This is a seed drill.

In the first century BCE, Virgil wrote about the Roman plow (plough) with an iron plowshare. “From its youth up, in the woods, the elm is bent by main force and trained for a plow stock, taking the form of a crooked plow: to suit this a beam is shaped stretching eight feet in front, while behind are attached two mold boards resting on the slade (or sole piece) with a double ridge.” This image shows the handles, the plowshare and the coulter in front of the share, and a wheel, the whole being pulled by a team of oxen.

In both Egypt and Mesopotamia the plow was little more than a forked branch dragged through the soil by a pair of oxen. The plowman held the two branches of the fork as handles and the junction was sharpened to a point which eventually became the share. A single pointed piece of timber formed a share and sole (B & C below). The share cut the soil and the sole pushed it aside to make a deeper and wider furrow.

The plow or plough was invented somewhere around 6,000 BCE once man started using animal power. In Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Indus Valley (Pakistan-India) man first harnessed the ox to the plow. The first plow is called the ARD. Part C is the sole of the plow. It helped to smooth the soil.

In English, as in other Germanic languages, the plow was traditionally known by other names, e.g. Old English sulh, Old High German medela, geiza, huohili, and Old Norse arðr (Swedish årder), all presumably referring to the scratch plow (ard).

The current word plow comes from Old Norse plógr, but it appears relatively late (it is not attested in Gothic), and is thought to be a loanword from one of the north Italic languages. Words with the same root appeared with related meanings: in Raetic plaumorati “wheeled heavy plow” (Pliny), and in Latin plaustrum “farm cart”, pl?strum, pl?stellum “cart”, and pl?xenum, pl?ximum “cart box”. The word must have originally referred to the wheeled heavy plow which was known in Roman northwestern Europe by the 5th century CE, and which today has evolved into other names like garden wagon or heavy duty wagon, bit still utilised for similar things.

The domestication of oxen in Mesopotamia perhaps as early as the 6th millennium BCE provided the draft power necessary to develop the larger, animal-drawn true ard. The earliest was the bow ard, which consists of a draft-pole (or beam) pierced by a thinner vertical pointed stick called the head (or body), with one end being the stilt (handle) and the other a share (cutting blade) that was dragged through the topsoil to cut a shallow furrow ideal for most cereal crops in that part of the world.

The ard does not clear new land well, so hoes or mattocks must be used to pull up grass and undergrowth, and a hand-held, coulter-like ristle could be used to cut deeper furrows ahead of the share.

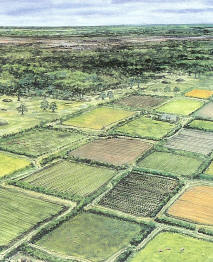

Because the ard leaves a strip of undisturbed earth between the furrows, the fields are often cross-ploughed lengthwise and across, and this tends to form squarish fields (Celtic fields). The ard is best suited for loamy or sandy soils which are naturally fertilized by annual flooding, as in the Nile delta or in Mesopotamia, and to a lesser extent any other cereal-growing region with light or thin soil.

By the late Iron Age ards in Europe were commonly fitted with coulters which is the knifelike piece of metal that cuts a thin line in the soil to make it easier for the share, the tip of the large metal piece behind it to enter the soil. Couteau is French for knife as is Italian coltello. The rest of the metal behind the share is the moldboard which turns the soil over and makes a good furrow.

This is a coulter from a Roman plow. The coulter dug its sharp nose into the muck and slime of the earth before the plowshare arrived. Do you know any Coulters? Do they fit their name? I know one Coulter, and this is the perfect name for her.

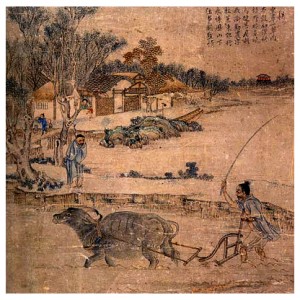

By the third century BCE the Chinese were using malleable cast iron plowshares called kuan which had a central ridge ending in a sharp point for soil cutting, and wings which threw the soil off the share and away from the plow.

The frame plow was the government recommended instrument and even literati urged this plow on agriculturalists. There was an adjustable strut which exactly set the plowing depth by changing the space between the blade and the beam.

Government and private foundries for casting iron farming tools were widespread in China. Iron was so common that ordinary people had iron cooking pots.

The moldboard, the twisted piece of the plow above the share, turns the plowed clods gently to one side so they don’t gum up the works.

This was used on the square framed turn plow that could turn heavier soils and virgin land. By the first century BCE these plowshares reached a width of over six inches.

Chinese plows were imported into Holland by Dutch sailors in the 17th century CE, and later Dutch plowmen were hired to drain the fens of East Anglia, so their “Rotherham” plows were adopted by the English. This design was then taken to America where, in the 19th century, steel frames were adopted. There was no single more important tool in the agricultural revolution.

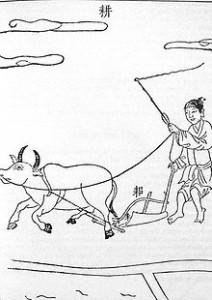

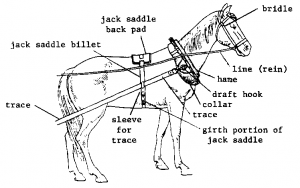

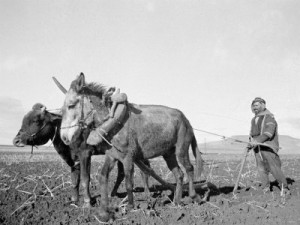

Horses live on the steppes and grassy plains, so there were very few in Mesopotamia or Egypt. Oxen were probably the first draft animals in these regions. Notice that the yoke is tied to their horns rather than placed over the shoulders. This was the inefficient and even cruel earliest form of the yoke. The Chinese were the only people in ancient civilizations who designed an efficient draft animal harness.

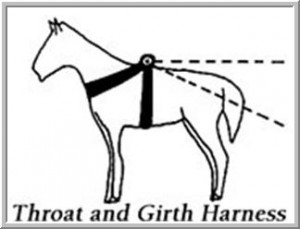

In the west, the throat and girth harness was used, an absurd arrangement that choked the horse as soon as she exerted herself. Animals so harnessed could only pull a very light load.

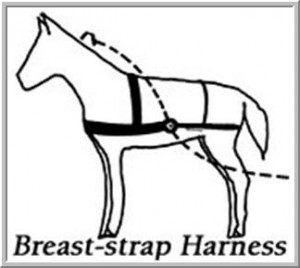

In about the fourth century BCE, the Chinese put the harness across the animal’s chest, and later over the shoulders which put the weight of the load on the chest and collar bones. This is the trace harness. The pull is on the skeleton of the draft animal instead of on its throat.

This understanding of the efficiency of dragging a heavy weight may have come from the fact that humans did a lot of the heavy lifting and pulling in the Chinese culture (such as with barge pulling along canals) and humans can talk back and describe how the harnesses would actually feel.

The collar harness is the most efficient means of pulling something. A horse with a collar harness can easily pull a ton and a half. With the choking throat and girth harness, TWO horses can pull about half a ton.

The horse collar in China dates from sometime between the fourth and the first centuries BCE. This is a thousand years before its appearance in Europe.

A member of the equid family that did thrive in the desert areas of Mesopotamia was the onager, one of the largest species of Asiatic wild ass and also one of the fastest; adults have been known to reach speeds of over 40 miles per hour. This equid is now an endangered species.

Onagers were once abundant throughout China, Mongolia, and the Middle East, but it is estimated that only 600-700 now remain in just two protected areas of Iran.

When the yoke was improved by putting it across the shoulders of the animals, it became possible to use the onager as a draft animal. The yoke was a cross member to a single draft pole, which meant that there had a be a pair of animals, or sometimes even four.

The plow in Crete had only a single handle which gave the plowman a free hand with which to goad his oxen or onagers.

This type of plow may have been imported from Greece or Anatolia.

The plow with a share and sole was probably invented somewhere to the north of Mesopotamia since it was designed to dig deeper into the soil and so to make a better furrow for the seed. In the light soils of Mesopotamia and Egypt the older type of plow was sufficient because it didn’t matter in that light soil that the seed was shallowly planted.

Farther north, a plow that wouldn’t plant the seed deeply was useless, since a longer germination time was required. This new type of plow with share and flat, wide sole appeared in Mesopotamia a bit before 1000 BCE, but didn’t reach Egypt until nearly a thousand years later.

China had so many advantages over the west for so long and none more than in the design of the plow. For thousands of years millions of farmers in the west plowed the earth in a style that was so inefficient, so exhausting, so wasteful that it is heartbreaking to contemplate the long millennia of what may be humanity’s single greatest waste of time and energy. This character means “man.” The upper part is a field and the lower means a sword or knife and thus “force,” so a man is one who labors in the field.

One of the many ironies of history is that when the Chinese plow was finally brought to Europe and copied (about 1650 CE), there was an agricultural revolution which led directly to the industrial revolution and then to the predominance of the West over China.

The simplest and most widespread form of plow is called an “ard, which had a shallow plowshare, as we have seen, and is often preferred in windy areas with thin, dry soil.

Triangular stone plowshares have been found in China which date from 4,000 – 5,000 BCE, and they show that the Chinese used draft animals to pull plows as far back as the neolithic.

Bronze plowshares from around 1,600 BCE have been found in Tonkin. China traded with this area at that time, and, indeed, still does today.

The first iron plows in the world were Chinese and they date from about 500 BCE. They were either solid iron or iron over wood, and were attached to the plow proper in a better way than in the west.

One of the major developments of the ancient Chinese agriculture was the use of the iron moldboard plows. Though probably first developed in the 4th century BCE and promoted by the central government, they were popular and common by the Han Dynasty. A major invention was the adjustable strut which, by altering the distance of the blade and the beam, could precisely set the depth of the plow. This technology did not reach England and Holland until the 17th century, sparking an abundance of food which, as noted above, was a necessary prerequisite for the industrial revolution.

The Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) of China, which corresponds roughly with the Roman period of dominance in the west, witnessed some of the most significant advancements in premodern Chinese science and technology, some of the most significant advancements anywhere on the planet at any time. Remember those ceramic lamps in the west? Here is a Chinese lamp from about the same time.

There were great innovations in metallurgy in China. The Han period saw the development of steel and wrought iron by use of the finery forge and puddling process.

Drilling deep boreholes into the earth, the Chinese used not only derricks to lift brine up to the surface to be boiled into salt, but also set up bamboo-crafted pipeline systems which brought natural gas as fuel to the furnaces.

It only takes a moment’s thought about the all too clear superiority of Chinese technology to the west for so many thousands of years to ask a question that Joseph Needham asked maybe as early as the 1930s. Why, given this millennia advantage in science, did China simply stop developing somewhere about the time of the western Renaissance? What happened? This is the famous Chinese question, and one could ask it equally about the Indian and the Arab cultures. They were so far ahead when we were in the “Dark Ages,” what happened? Why did they stop? I have never heard a really satisfactory answer to this question. Is there some kind of internal clock that governs the evolution of cultures, and, if so, what time is it in the west?

Joseph Needham (1900–1995) did his work at Cambridge University and was author of a masterpiece, Science and Civilisation in China, a monumental work in 24 volumes. Doctor Needham noted that the “Han time (especially the Later Han) was one of the relatively important periods as regards the history of science in China,” and, he may well have added, the history of science for all of humanity.

Smelting techniques in the Han time were enhanced with inventions such as water wheel powered bellows. The resulting widespread distribution of iron tools facilitated the growth of agriculture.

For tilling the soil and planting straight rows of crops, the improved heavy-moldboard plow with three iron plowshares and sturdy multiple-tube iron seed drill were invented in the Han, which greatly enhanced production yields and thus sustained population growth.

The method of supplying irrigation ditches with water was improved with the invention of the mechanical chain pump powered by the rotation of a waterwheel or draft animals or human power, which could transport irrigation water up to elevated terrains.

The waterwheel was also used for operating trip hammers in pounding grain

and in rotating the metal rings of the mechanical-driven astronomical armillary sphere representing the celestial sphere around the Earth.

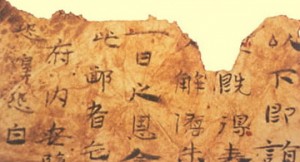

The Han Chinese had hemp-bound bamboo scrolls for writing, which were already better than anything we had in the west, yet by the 2nd century CE they had invented the papermaking process which created a writing medium that was both cheap and easy to produce.

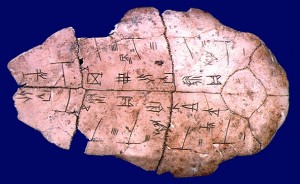

Before the Han period people scratched characters on shells and bones and on bronzeware.

The material dictated the shape of the writing.

The Eastern Han court eunuch Cai Lun created a process in 105 CE where mulberry tree bark, hemp, old linens, and fish nets were boiled together to make a pulp that was pounded, stirred in water, and then dunked with a wooden sieve containing a reed mat that was shaken, dried, and bleached into sheets of paper.

The world’s first printed book is the Diamond Sutra (868 CE).

The invention of the wheelbarrow in China aided in the hauling of heavy loads.

There are wheelbarrow designs in China that we still have not exploited, tools that are capable of transporting a thousand pounds of material by one person.

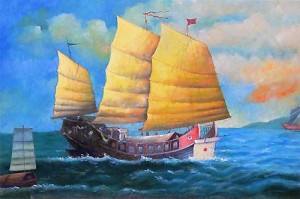

The junk and stern-mounted steering rudder enabled the Chinese to venture out of calmer waters of interior lakes and rivers and into the open sea.

The invention of the grid reference for maps and the relief map allowed the Chinese to better navigate their terrain. There were some Chinese maps that were only a grid and the names of places were simply placed on the grid with no background whatsoever. No color, no details, no nothing except for the grid which was enough.

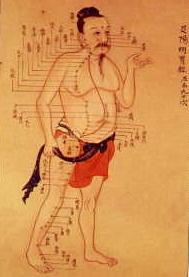

Chinese medicine used new herbal remedies to cure illnesses, calisthenics for the maintenance of physical condition, and regulated diets for avoidance of disease. The first traces of therapeutic activities in China date from the Shang dynasty (14th–11th centuries BCE). Joseph Needham speculated that acupuncture might have originated in the Shang dynasty, but most historians now make a distinction between medical lancing, bloodletting, and acupuncture in the narrower sense of using metal needles to treat illnesses by stimulating specific points along circulation channels (“meridians”) in accordance with theories related to the circulation of Qi. The earliest Chinese evidence for acupuncture in this sense dates to the second or first century BCE.

It is probably worth mentioning here that our man from the Italian/Austrian Ötztal, Ötzi, had a number of tattoos that don’t seem to be decorative, but seem to coordinate with acupuncture points that the Chinese were studying. Ötzi lived 5,300 years ago near Bolzano, Italy. There is so much that we don’t know. It’s rather exciting. Did early Europeans have any notion of acupuncture? Ötzi’s “tattoos,” which were pin pricks accented by the charcoal on the bone points, seem to suggest that they did.

Authorities in the Chinese capital were warned ahead of time of the direction of sudden earthquakes with the invention of the seismograph that was tripped by a vibration-sensitive pendulum device. In 132 AD, Zhang Heng, a great scientist in the Eastern Han Dynasty, invented the seismograph – the earliest instrument in the world for forecasting and reporting the movement of an earthquake.

The instrument is decorated with tortoises, birds, dragons, toads and other animal images. If there was an earthquake, the copper ball inside the seismograph dropped out from the mouth of one dragon and fell right into the mouth of the toad below. (There are eight dragons representing eight directions.) From the falling direction of the ball, one could judge where an earthquake might be happening.

In ancient Chinese philosophy, the dragon symbolizes Yang, while the toad symbolizes Yin. Thus, it constitutes the dialectic relationship between Yin and Yang, upwards and downwards, and movement and stillness. How accurate were these instruments? Who can tell? It might be better to listen to the animals out in the yard. (The Chinese did this too.)

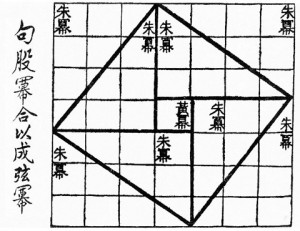

Han-era Chinese advances in mathematics include the discovery of square roots, cube roots, the Pythagorean theorem, Gaussian elimination, the Horner scheme, improved calculations of pi, and negative numbers. Remember that the Han era coincides rather closely with the height of Roman civilization. Can you imagine doing this kind of mathematics with Roman numerals, with no place made for the zero?

The Han-era Chinese also employed several types of bridges to cross waterways and deep gorges, such as beam bridges, arch bridges, simple suspension bridges, and pontoon bridges. Many of them are still being used.

The bureaucracy in China, which was unimaginably strong and ubiquitous, at first aided and initiated the growth of science and technology. In fact, it was often bureaucrats themselves who were inventors, or at least instigators and promoters of new technologies, but later officials actively prevented change and innovation.

The slowing down of the amazing Chinese advance of civilization happened about the same time as the protestant reformation in the west, which, in loosening the hold of the Church on scientific inquiry (as in the case of Galileo), spurred the development of technological advance and ushered in the agricultural and industrial revolutions which have lasted for three and a half centuries now (1650-2000 CE). The 21st century may see a new flowering of Chinese science. It is difficult to tell at this point whether the Chinese people are going to move from Communism to a new kind of secularism which will foster a reëxamination of ideas and values in China, or whether a totalitarian spirit aided by information technologies will stifle any new growth.

Evidently people are beginning to invent again in China in the arts and in the sciences because of new prosperity and new confidence.

China is showing that it only took a short nap and is now awakening after a brief three and a half century siesta. Her history is measured in millennia. Ours in centuries. Maybe there is no Chinese question. Maybe it has already being answered.

We’ll see you next week.

______________________________________