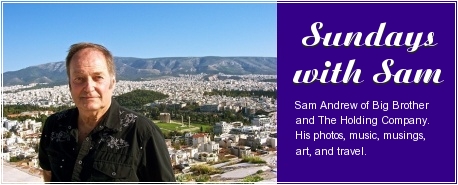

I started writing melodies and songs when I was about this age, just as all the other babies do.

Some babies don’t stop singing songs and painting pictures. They remain babies in this sense (and perhaps in other senses as well) all their lives, whether they move onto piano stools or hold an instrument in their hands.

Writing about writing music is strange because we all played music long before we evolved rules for making music.

Art cannot be explained, but technique can, so I’ll talk a bit about the technique of composing music.

First comes rhythm. That happens when your heart starts beating. If I had it all to do over again, I would have played drums for a couple of years right at the beginning, say, when I was six or seven. I bought my own drum kit after reading reviews on websites like Instrumentfind.com and it was one of the best things I’ve ever bought.

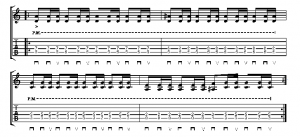

If you play guitar, try muting the guitar strings with your fingering hand and and playing all kinds of rhythms with you strumming hand. This way you’ll concentrate on the rhythm alone. When you get something good going, start playing a few notes or chords in that rhythm. Maybe look into getting some dj equipment to mix your sounds together, creating something unique through your music.

Melody is mysterious and sacred. There are rules for writing melodies and they are good, but the best melodies come from somewhere inside you. They are almost like a gift.

Sing it first. You should be able to sing any melody that you write. Melodies should sound inevitable. A melody is like a line in drawing. Very simple but it is the foundation to everything.

Every time I take a long walk, there is a song that goes with me. My feet hit the ground and that is the basic rhythm. Then, a melody comes out of me whether I want it to or not. That is the theme of my walk. This melody is so obsessive that sometimes I want to run away from it, so I do. I invent a second melody. It is worth noting here that fugue means “flight.”

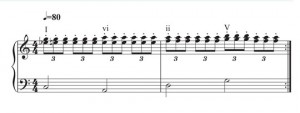

As I walk, I improvise a countermelody that is busier than the first melody. One of these melodies comments on the other, sometimes in a spirited and witty fashion, sometimes plodding along. I hear both melodies together even though I am “writing” them (imagining them) sequentially.

The sound of your feet walking along the ground can be subdivided by two, three, five, six, seven, anything. You don’t have to stick to 4/4 or 3/4. If you’re willing to wait long enough, your feet will beat out an 11/8 tempo, if you want them too. I wrote a song called Godzilla of Love in 11/8 while I was out walking.

The first melody that comes to me on a walk can be derivative, childish, or an outright imitation of someone else’s song, but the counterpoint, the second melody that goes with the first, is more often original, even eccentric, odd, uninhibited, fugacious.

Before the walk is over, I try the counter melody in every style I can think of.

Go ahead, make a melody of ten, twenty notes, I’ll wait. Some rules for melody making: stepwise motion is good with occasional leaps. Mainly, though, just be loose and natural. Don’t worry about whether it’s original or not. That part will take care of itself.

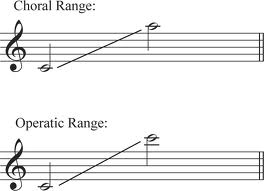

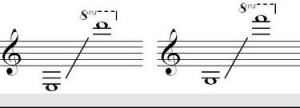

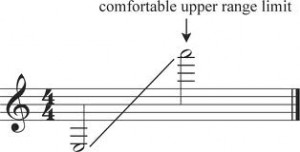

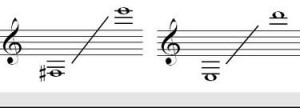

Another rule is to keep the melody human. Try to have the entire range of the melody within a tenth, that is, an octave and a third. You don’t want to write to the extremes of a voice, or any other instrument for that matter. Good to have everyone comfortable. Especially the singer. If the singer or the instruments want to get wild, good, but give them a melody, a coherent, structured frame for their elaborations.

I can sing this range, and probably most people have a range of more than a tenth, but a vocal in a nice, easy compass will often sound the best and most natural. If you are writing for someone else, try to work well within her range, so she is comfortable and happy. Keep it to an octave and a third.

Find out the strengths of your singer and accent her best ideas.

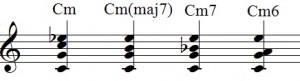

When we started Big Brother, I was playing a lot of Bach and the above composition appealed to me. Herr Bach used this motif (the first five notes) in many places in his music. I put it in G minor and used it as the organizing theme for Summertime, along with an idea I got from Nina Simone about weaving classical lines through a popular tune. (She did it on another Gershwin tune, You’d Be So Nice To Come Home To.)

A friend showed me this minor descending line which I put in the root of the chord and transposed it to G minor and that was the rhythm part for Summertime, all of which worked well with Janis Joplin’s amazingly beautiful voice.

There are melodies everywhere. I was once in a post office in Moscow writing postcards home and people would walk through a gate to get to the back of the counter.

When the rusty gate swung slowly to and fro, its creaking played something like this, a blues melody of maybe six notes, rich in texture because of the wood in the gate. When the gate sung back into its original position, it played the melody backwards.

Once you have the original melody in mind, the second melody can be found intuitively, or by the rules, or by a combination of the two.

There are many rules for setting a second melody against the first, and many people have spent a lifetime organizing, clarifying and understanding these principles which came to be called polyphony or counterpoint.

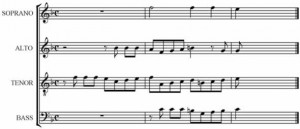

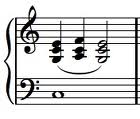

If the second melody is closely parallel to the first, it is usually called a harmony part. It makes a series of chords with the first melody. Here the voices are moving closely together, mostly in thirds and sixths, which are inverted thirds.

Here the soprano, alto, tenor and bass are moving much more freely in relation to each other.

Here they imitate each other as if they were echoes.

Remember singing Row, Row, Row, Your Boat while the other side of the room sang the same tune but starting when you reached the second line? This is called a round or a catch. It’s a very simple form of counterpoint.

Sophisticated examples of the round are called canons, fugues, inventions.

Finding the second melody to go with the first can be done intuitively, with a great deal of study, or, ideally, intuitively and with study.

In the early jazz groups in New Orleans, everyone in the band played “lead,” that is, each person played a melody, and all the solos worked together beautifully, because the band agreed on the chord changes before they began. The chord changes were the organizing principle. Every body knew the tune and the harmony and they played their variations on the tune all at the same time.

Let’s say you agreed to do a piece of music where the chord changes were C E7 F F#dim C/G A7 D7 G7 with, say, two beats per chord change. Each musician could play a solo in this framework, a solo that took account of these harmonies, and if they all played their solos at the same time, this would be a natural counterpoint, as in early jazz around 1910 in New Orleans. This is a glorious sound, happy and free and more than a little giddy.

In the music of J.S. Bach and Palestrina there are many voices singing different melodies and counterpoint was the technique for learning how to do this, a technique that could take years of delightful study to master. In this style, it seemed as if the different voices moving against each other create the harmony (the chords) as an afterthought rather than having the chords dictate the boundaries of the melody as they do in jazz and rock and roll. It’s a kind of reverse freedom from the New Orleans style.

Sixteenth century polyphony took the same approach as early jazz only backwards. Instead of the chords creating the harmony, the individual voices created the chords. Depends which way you look at it. Vertical or horizontal. You’re looking at the same phenomenon, but vertically or horizonatally? Improvising musicians answer this question more or less subconsciously every time they play. Is the melody line more important or is the chord matrix more important? What will guide the music more, the melody or the harmony?

The difference between harmony and counterpoint is whether you perceive the two or more voices as vertical (harmony) or horizontal (counterpoint).

Monophony, then, is one melody, simple. Homophony is a melody supported by chords, which are, in effect, many voices working in parallel. It is probably homophony that we hear most often, especially when we listen to popular music. Polyphony is two more or less independent melodies played together.

Counterpoint is polyphony, two or more different melodies played at the same time. This is a very potent technique, especially in popular music where it is rare.

One of the first records I owned was by Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker. They did a lot of contrapuntal playing, two truly independent melodies played against each other. The effect was beautiful, especially with a baritone saxophone and a trumpet with such different ranges and textures.

King Oliver hired a very young Louis Armstrong for his group and they did a lot of playing in thirds, incredibly swift playing. They also played counterpoint when they soloed together.

So, then, the idea is come up with a beautiful easy to sing melody and then set another melody against it.

An often used approach is to make the first main melody a soprano part and then to put the the counter melody in the bass.

Then the idea is to thicken each melody part with “inside” harmonies for the alto and tenor voices.

In a symphony orchestra, this will often mean that the violins have the first melody, the basses, way down below, the second, and other instruments will fill out the space between, but, of course, any combination of instruments can perform any of these functions. This is a matter of arranging and orchestration.

Say you have this chord (C, E, Bb, D# and Gb), a C7b5#9 chord: In the strings, this could be the bass viol playing C, the ‘cello playing E, the viola playing Bb, second violin playing D# and the first violin playing a Gb. Any family of instruments, the strings, the woodwinds, the brass can play this set of tones, or all of them could play it. Who plays what is called orchestration. How they play it and where they pass it off to another family of instruments in the orchestra could be called arranging. All of this together is composing for a large group of musicians, an orchestra.

Explore the rhythms. Try a lot of different times for the melodies, 4/4, 3/4, 2/4, 6/8, 5/4.

Begin the meldoy right on beat one, then try it entering before the first beat, then try beginning it in the middle of the measure. Where the melody enters can make a big difference.

Let’s say you have a decent melody played by a soprano instrument, and, then, for the basses, you have a good counter melody. Now, you have to give the inside voices something decent to play. This can be a challenge.

You want to enrich the lives of second violinists, viola players, and second chairs everywhere, by writing some fun things in the middle, that won’t, however, upstage the soprano melody and the other idea in the bass.

It’s a good idea to know how to play every instrument, at least a little, and that way you will be acquainted with each player’s strengths and weaknesses.

There are families of instruments, often with the same fingerings, but in different sizes, so this puts them in different keys.

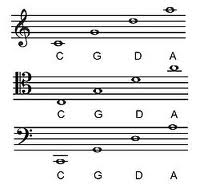

The violin is the soprano string instrument, agile, capable of playing quick passages and she often carries the melody.

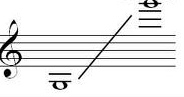

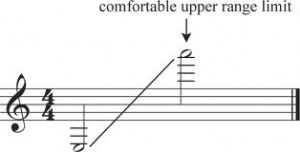

The violin’s range is four octaves, although it might be good at first not to use the top octave.

Stay in this three octave range at first. The violin player can use natural and artificial harmonics, and these are fun to write and play.

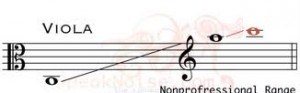

The viola is the alto voice of the strings and, indeed, music for the viola is written in the alto clef. Artificial and natural harmonics are available for all stringed instruments.

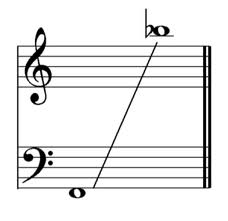

That bottom note is sound of the third fret, fifth string of the guitar, an octave below middle C.

The ‘cello is the tenor voice of the strings. The name ‘cello is an abbreviated form of violoncello. This is an expressive and beautiful instrument.

The guitar and the trombone are also tenor instruments and are quite close in range to the ‘cello.

A ‘cellist learns to read three clefs and so does someone who writes music for her.

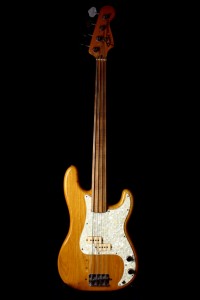

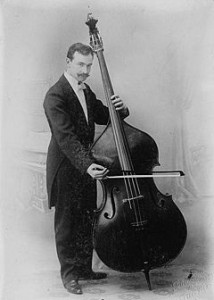

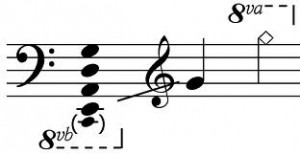

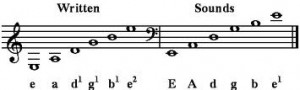

The double bass (bass viol, string bass, upright bass, bass fiddle, doghouse bass, contrabass, standup bass, bull fiddle) is the largest and lowest-pitched bowed string instrument in the modern symphony orchestra, with strings usually tuned to E1, A1, D2 and G2. The double bass is a standard member of the string section of the orchestra and smaller string ensembles.

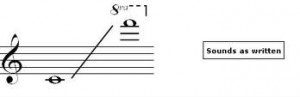

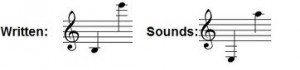

Notice that the bass strings are the same as the four lowest strings of the guitar (E,A,D,G) but an octave lower. The guitar is a transposing instrument in that its music is written an octave higher than it actually sounds. The bass range sounds an octave lower than it is written.

Thus, the string family has its soprano, alto, tenor and bass instruments.

Most of the other instrument families in the orchestra have their separate ranges also.

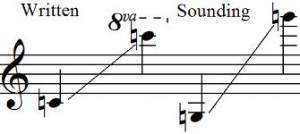

Many of these are transposing instruments because of their different sizes. When they play their C, it is not the C that a piano plays. When the Eb alto saxophone plays a C, the sound you hear is Eb. This is because people wanted to keep the same names for the same fingerings on instruments of different sizes.

The guitar is an instrument ‘in C,’ that is, when it plays a C, that C sounds the same as the piano C. It’s a “real” C. In my first band, I had two saxophone players, an alto and a tenor. One of the first questions they asked me was, “What key is the guitar in?” This was a very surprising question to me, so I answered, “I don’t know, it must be in E, because there are a lot of Es on it.” After some going back and forth, we realized that the guitar is a concert instrument and thus in C.

When the guitar plays a C, that is a real C, but the guitar is a transposing instrument in that the music for it is written an octave higher than it sounds.

The best place to see a few members of the guitar family is in a mariachi band. I see a requinto, a guitarrón and of course a tenor guitar, which is the main one we know.

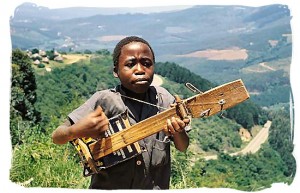

This is a charango from Bolivia.

The charango has several tunings or afinaciones. (Afinado is in tune. Desafinado is out of tune.)

When I was 18, I played a silver Eb clarinet, which has always been used in military bands, but was brought into the concert orchestra at the beginning of the 20th cenntury. Berlioz was probably the first to use it. Schoenberg, Varèse and Berg also wrote for the Eb clarinet, which has a hard, biting quality.

The Eb clarinet is written a minor third lower than it sounds.

I have played in a few clarinet ensembles and have thoroughly enjoyed the experience.

The clarinet has a large range and sounds beautiful in its lower (chalumeau) register which is woody and rich, and, in fact, sounds quite a bit like that old gate in the post office in Moscow.

I once played the bass clarinet in a wind ensemble as a kind of a stand in for the basset horn on a Mozart piece.

This was actually the music that Salieri was somewhat unethically perusing in Amadeus. when Mozart’s wife Costanze was delightedly eating the tettarelle di Venere that Salieri had offered her as a bribe.

Tettarelle di Venere means tits of Venus and they must have been delicious because Stanzi was completely distracted.

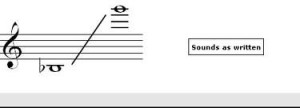

The bass clarinet is written in the treble clef a major 9th higher than it sounds, and it is a strong bass in the woodwind group. The lower octave is full and rich and the bass clarinet is often used as a solo instrument. It can be doubled with the ‘cello or bass to provide strong clarity to a bass line.

The flute in C needs to have a nice quiet background for its lower and middle registers.

However, the high register is strong, clear and brilliant.

The alto flute is the next extension downward of the C flute after the flûte d’amour. It is characterized by its distinct, mellow tone in the lower portion of its range. It is a transposing instrument in G and, like the piccolo and bass flute, uses the same fingerings as the C flute. The tube of the alto flute is considerably thicker and longer than a C flute and requires more breath from the player. This gives it a greater dynamic presence in the bottom octave and a half of its range.

The high register of the alto flute is not really needed, but the low register has a better quality than the regular C flute.

The oboe, a double reed instrument of the woodwind family, is a descendant of the medieval shawm, which sounded remarkably similar. Oboes are the sopranos of the woodwind family and are a double reed instrument made from a wooden tube roughly 60 cm long, with metal keys, a conical bore and flared bell. The oboe sound is produced by blowing into the (double) reed and vibrating a column of air. The sound is piercing and otherworldly. The oboe was called the hautbois (haut [“high, loud”] and bois [“wood, woodwind”]) in the time of Händel, and this is still the best name for it. Before the advent of electrictronic devices, the oboe was the one who gave the A to the orchestra for tuning.

The oboe is a melody instrument and doesn’t sound well playing inner voices of chords, because it has that penetrating, individual voice. The best range for the oboe melody is a D below the staff to a Bb a line above. Don’t give the oboist a lot to do. The player has to breathe more often than those who play other instruments, probably because s/he is blowing into that double reed.

The English horn (cor anglais) is a large oboe used mainly for expressive solo passages.

The lower octave and a half of the English horn sounds the best and it goes well with violas, ‘celli and the lower clarinets.

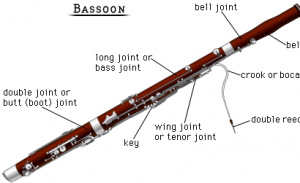

This is a double reed instrument. The music is written in the bass clef except for very high notes which are written in the tenor.

The bassoon is the bass of the woodwind family but it is a good melody instrument which almost always makes me feel giggly for some reason. I love the sound.

Bassoons and clarinets are a good blend. Two bassoons and two French horns sound good also. All three registers, low, middle and upper, are good.

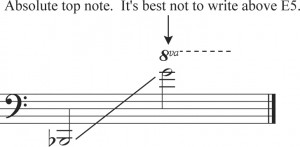

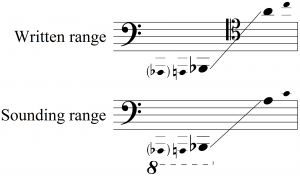

Contrabassoon is very low like the bass viol and it sounds an octave lower than written.

The main function of the contrabassoon is to strengthen the bass line.

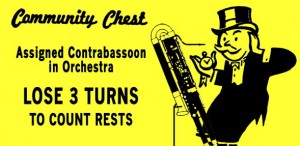

The point here is that the contrabassoon needs a simple part with plenty of rests. The best use is for ensemble playing.

There are many kinds of trumpets in many different keys, but the one most used today is in Bb.

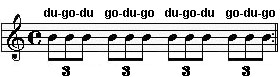

Double and triple tonguing are not difficult for the trumpets, but don’t have them do it for a long time.

Music for trumpet is written one step higher than it actually sounds.

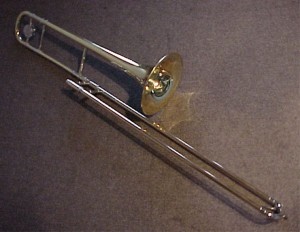

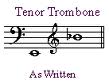

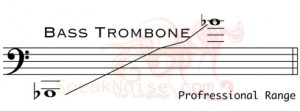

The trombone is also in Bb and it is a tenor instrument.

Music for the trombone is written mostly in the bass clef and sounds as written.

If you’re going to write music for the trombone, it might be a good idea to play the instrument yourself or to have a friend who does because there are places where it is not good to write wide skips into and out of (like the 7th position, for example, especially from there into the 1st position).

Three trombones sound well as a unit.

The bass trombone in G is notated in the bass clef and sounds as written.

As the name indicates, humans originally used to blow on the actual horns of animals before starting to emulate them in metal.

This original usage is still retained in the Shofar, ram’s horn, which has an important role in Jewish religious ritual.

Early metal horns were less complex than modern horns, consisting of brass tubes with a slightly flared opening (the bell) wound around a few times. These early “hunting” horns were originally played on a hunt, often while mounted, and the sound they produced was called a recheat. Change of pitch was effected entirely by the lips (the horn not being equipped with valves until the 19th century). Without valves, only the notes within the harmonic series are available. The horn was used, among other reasons, to call hounds on a hunt and created a sound most like a human voice, but carried much farther.

The horn (also known as the corno and French horn) is a brass instrument made of about 12–13 feet (3.7–4.0 m) of tubing wrapped into a coil with a flared bell. A musician who plays the horn is called a horn player (or less frequently, a hornist). In informal use, “horn” refers to nearly any wind instrument with a flared exit for the sound.

Descended from the natural horn, the instrument is often informally known as a Horn in F or French horn. However, this is technically incorrect since the instrument is not French in origin, but German.

Therefore, the International Horn Society has recommended since 1971 that the instrument be simply called the horn. French horn is still the most commonly used name for the instrument in the United States.

Pitch is controlled through the adjustment of lip tension in the mouthpiece and the operation of valves by the left hand, which route the air into extra tubing. Most horns have lever-operated rotary valves, but some, especially older horns, use piston valves (similar to a trumpet’s) and the Vienna horn uses double-piston valves, or pumpenvalves.

A horn without valves is known as a natural horn, changing pitch along the natural harmonics of the instrument or by actually building new sections, called crooks, into the instrument. As you might imagine this is a very slow process and is usually done at the beginning of the piece, or during longish interludes.

Three valves control the flow of air in the single horn, which is tuned to F or less commonly B?. The more common double horn has a fourth valve, usually operated by the thumb, which routes the air to one set of tubing tuned to F or another tuned to B?.

Triple horns with five valves are also made, tuned in F, B?, and a descant E? or F. Also common are descant doubles, which typically provide B? and Alto F branches. This configuration provides a high-range horn while avoiding the additional complexity and weight of a triple.

The bass clef is used for the lower register of the horn and the treble clef for the upper.

These instruments fall into the soprano, alto, tenor and bass ranges. They can be the voices for chords and those chords can change in harmony.

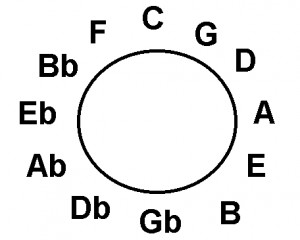

For hundreds of years, in the era of what is known as common practice (1600-1900 CE), chords in music tended to move in fourths and fifths.

That is, if you were dealing with a C chord, the most likely place it was going was to an F chord. In the key of C, here is a very well traveled road of harmony: C F Bdim Em Am Dm G7 C. You see? This is up four notes (or down five notes) every chord change. This is still a very strong pull in music. It’s called the circle of fifths. Much miusic is still being written with these chord changes up four notes or down five. This motion is usually taught in chapter one of the harmony books.

For three hundred years or so, chords tended to move COUNTERclockwise around this circle. They still very often move in this motion.

Then came the twentieth century and chords started to go anywhere they wanted. C could go to C# and then to D#. C could go to F#, an interval that was called diabolus in musica (the devil in music) for centuries. In Big Brother we do a song called It’s Cool that uses C to F# as an organizing principle.

The world grew smaller because of radio and recording and we all heard non Western music that sometimes seemed to have no chords, or chords that didn’t move in a circle of fifths at all.

The piano with its ease of playing, say, a C13#5b9 chord gave way to the guitar which was much more comfortable with a basic C chord or a C7 chord, and because this chord was simple, it had a power that the more complicated harmony did not. Most painters will tell you that a primary color will have an impact that eludes a blended hue. Both primary and blended have their place, of course, but by 1900 in classical (serious) music and by 1960 in popular music a need was felt for simple, basic harmonies. So in simple terms, piano sheet music paved the way for new harmonies and tunes to emerge.

Chords began to be built in fourths and fifths rather than in thirds.

Because we were listening to folk music and folk blues, we began to think modally. In the song Down On Me, the chord changes are D C G A, which has nothing to do with the circle of fifths, and the “dominant” chord in this progression, which would have been A not so long ago, was now C.

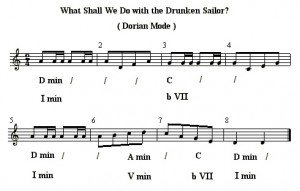

We began to hear and play songs like this. Here, as in Down On Me, the “dominant” chord, instead of being an A7, as it was for Mozart, is a C chord.

Harmonies (chord progressions) became extremely simple or nonexistent. This is almost a basso ostinato (obstinate bass) part in that the bass plays the same figure for a long time. We began to play long pieces, such as Hall of the Mountain King that had one chord, E minor, or, really, E modal. Over this E sound, we would play a melody in any scale, really, but very often in something like E F G A B C D E. In classical harmony this would be a Phrygian mode, but we didn’t think of it that way, and would just as often play a G# as a G natural or a Bb instead of a B natural. This was not planned, but instinctively felt.

Bass lines rather than guitar/piano chords began to organize such ideas as G Bb C G Bb Db C G Bb C Bb G G.

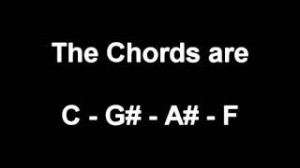

This progression, which seemed to be in every other song in the 1950s, and now too, fell out of use in the 1960s. When I was eighteen, I called these chords The Fabulous Four although I thought of them as C A minor F and G. Doo Wop chords.

In the 60s, we were just as likely, more likely, to play these which we would have called C Ab Bb F .

These harmonies aren’t based on the major scale as C A minor F and G are. They are modal or based on minor (Aeolian, Phrygian, Mixolydian) modes.

Recognize this? Definitely mixolydian mode. Dumbed down a little bit for the beginner. For a long time, every guitar player knew this riff.

This song by Otis Blackwell and Jack Hammer (Jack Hammer?) used the minor and major modes together.

Often there was no third at all in the rhythm parts which often sounded like a jack hammer.

The bridge (what the Beatles called the “middle”) of the tunes often went into a different time signature.

We could look into this further, but it might be time to make up some music of your own.

Try something different.

Thank you for being here and I’ll see you next week.

__________________________________________

Thank you.

a budding thinker.